Indian Council of World Affairs

Sapru House, New DelhiStrengthening India-Central Asia Relations: An Approach, 7 September 2020

A renewed outreach by India to develop closer ties with Central Asia has become imperative. This is important not only by itself in security, strategic and economic terms, but also as an increasingly important element of India’s long-term relations with Afghanistan. As Pakistan’s influence in Afghanistan grows, riding on the back of the Taliban, India needs to further strengthen its links within Afghanistan as also with Iran, Russia and Central Asia. There are clearly significant differences between the Central Asian Republics and more so between them and Afghanistan. However, from the standpoint of policy formulation, there is an underlying interlinked, structural coherence for India.

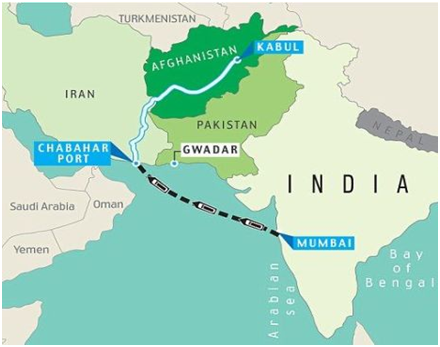

(Source: Maps of India)

To begin by stating the obvious, the Central Asian Republics are landlocked like Afghanistan; but more importantly, the populations have goodwill towards India and would like to see India more actively engaged as a balancing force. For Afghanistan, the balancing would continue to be vis-à-vis Pakistan, as the Pak ISI seeks to turn Afghanistan into a client state or one where it wields disproportionate influence through its proxy - the Taliban leadership, which it shelters and manipulates. For the Central Asian states, India could be a balancing force vis-à-vis China as the growing economic clout of China looms ever larger over these countries, particularly their fragile economies. It is a given that no sovereign nation wants to be too dependent on another, or have a one-sided relationship that restricts its decision-making ability.

The policy focus for India with regards to Central Asia, therefore, suggests itself automatically. The policy most likely to bear early results is one that prioritizes economic relations. To delineate this more narrowly within the economic domain, it would, in a nutshell, be focused on: adding dynamism to business-to-business relations between India and the Central Asian countries. And that too quickly as time is of essence. On the face of it, this seems straightforward, but the devil lies in the detail. The constraints are numerous starting with the above-mentioned landlocked nature of the countries impacting a free-flowing trade, and more so the track record has not been noteworthy. In fact, the record of India-aided projects in Central Asia has been dismal. Overcoming these two constraints relating to: (i) means and ways of transportation; and (ii) efficiency in the execution of joint projects, as we have amply demonstrated in the past 17-18 years in the case of Afghanistan, hence become critical.

Points to consider, measures suggested:

Facilitation by Indian Missions in Central Asia, Afghanistan and Iran to enable Indian businesspersons to increasingly use Chabahar port in Iran in addition to the Bandar Abbas port for transit purposes. A brief case study as illustration: An Indian company has been importing food grains from Uzbekistan to India on a regular basis. In April 2018, it imported two containers of food items to India through Afghanistan trying to avail the services of Chabahar port, in the Gulf of Oman. However, due to some reasons the two containers were detained at the Hairaton border in Afghanistan. When the company head approached (13/04/18) the Afghan Embassy in Tashkent to seek visa so as to visit Afghanistan and resolve the matter, he was advised to get a supportive letter or a telephone call from the Indian Embassy in Tashkent. Unfortunately, he could not be helped by our Mission. Then his local partner, an Uzbek company, approached the Uzbek consulate at Mazar-e-Sharif. The Uzbek Consulate Head in Mazar promptly visited Hairton Customs and resolved the issue, thereby returning the containers to Uzbekistan. The containers were then routed through the Bandar Abbas route.

The point being highlighted here is that unless the concerned Indian Missions & other offices down the line are sensitized to accord importance to strengthen trade relations in general, and especially to encourage the use of Chabahar port (in the Sistan-Baluchistan province of Iran), operationalisation of the port will not be as envisaged. Simultaneously, businesspersons already invested in trading with Central Asian Republics need to be encouraged by conveying that their trading activities with the region would be facilitated. Business organizations and think tanks with links in the region can play a role in facilitating Indian businesspersons, who have trading links with Central Asian countries, by acting as a reliable link with the Ministry of External Affairs and other ministries.

The Central Asian business/trading space has its own peculiarities as the shadow of Communist era structures and practices still remain. Secondly, language is a factor - knowledge of Russian or the national language is a major advantage as English is spoken by a small fraction of the population. To navigate these and be acquainted with the local socio-cultural practices, businessmen already experienced in trading with the region need to be facilitated for an early impact.

The usual seaport for Indian businesspersons trading with Central Asia has been Bandar Abbas. However, due to the U.S. sanctions, its use has been restricted resulting in lower trade volumes. To illustrate the impact of sanctions on transit trade through Iran: despite instructions by the RBI, Indian exporters are not being issued BRC/e-BRC (Bank Realisation Certificate) by Indian banks for transit of goods through Iran for destination to a third country – Afghanistan, Central Asia or Russia, even though the exporter has already received payment in foreign currency in the bank and the bank has deducted a service charge to credit the amount. Chabahar port, on the other hand, is not under U.S. sanctions and is closer to India’s west coast, to ports like Mundra and Nhava Sheva. Chabahar port can in the present circumstances be promoted to access the Central Asian region and beyond, more effectively.

Chabahar’s salience for us increases further in view of the growing Chinese footprint in Iran. It is, therefore, suggested that meetings with a logistics company working in India, Iran, Afghanistan, Central Asia and Caucasian countries can be held to explore ways to do this. Understanding with the logistics company would not be to manage the port, but only to facilitate inter-country trade using the port. Such an arrangement could help, to a large extent, smoothen frictions relating to trade between India and Afghanistan, India and the Central Asian Republics and India and Russia.

India could also encourage other friendly countries to use Chabahar port for their trade with Afghanistan. For instance, a few weeks back, a consignment of 16000 metric tonnes of fertilizer was exported by Australia to Afghanistan using the Gwadar port. With improved logistics at Chabahar and its growing use, such traffic could be channelled through Chabahar.

Due to the ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic, the transportation of goods between Central Asia and India and vice versa has been affected. Cargoes between India and the Central Asian states through the sea route have declined sharply. Further, the passenger-cum-cargo flights have almost entirely stopped. To illustrate, the following passenger and cargo flights were in operation till March 2020:

Passenger flights, these also carry commercial goods:

- Tashkent-Delhi-Tashkent (five flights in a week by Uzbek Airways)

- Tashkent-Amritsar-Tashkent (two flights in a week by Uzbek Airways)

- Tashkent-Mumbai-Tashkent (two flights in a week by Uzbek Airways)

- Almaty-Delhi-Almaty (seven flights in a week by Astana Airways)

- Bishkek-Delhi-Bishkek (once in a week, but irregular, by Kyrgyz Airways)

- Dushanbe-Delhi-Dushanbe (once in a week, but irregular, by Tajik Airways)

- Ashgabat-Delhi-Ashgabat (one/two flights in a week by Turkmen Airways)

Cargo flights:

- Tashkent-Delhi-Tashkent, as per need.

All these flights have stopped, except for the cargo flights from Tashkent on a weekly basis. Such a dire situation, however, also presents an opportunity to reassess and quickly overhaul trade relations.

As stated above, currently, the favourite route for exports from India to Central Asia is through Iran’s Bandar Abbas port, and from there on via Turkmenistan. The unpredictable nature of dealings at the Turkmen border results in cargo loaded in railway wagons and in containers left stranded at the Sarakhs (Iran) – Serakhs (Turkmenistan) Check Point on the Iran-Turkmenistan border. Due to current restrictions on movement of cargo by road imposed by Turkmenistan, cargo containers bound for India have started using the Uzbekistan-Azerbaijan-Iran-India route instead, which increases the period of transit and freight charges.

At the Torkham border post in Pakhtunkhwa (Pakistan) the situation is often much worse. Depending on the ground situation, transit passage for trucks going to Wagah-Attari border check point gets obstructed. Since July 15, a restricted number of trucks (20-25 trucks, mostly carrying black raisins, Liquorice roots or Mulethi, Almonds, carrom seeds, etc.) have started arriving at the Attari border post from Afghanistan. However, this route is entirely dependent on the mercy of the Pakistani authorities, who tend to close it at the slightest pretext.

To avoid such problems, if Chabahar port is promoted and a reputed logistics company involved to tide over the nitty-gritty and paperwork, access to Central Asia will become significantly easier. Afghanistan can be a transit point for transportation of goods to the Central Asian Republics and vice versa. In the process, the Afghan economy gets a boost in the form of increase in transit fees collections. It would also provide employment opportunities to the Afghan people as their help would be required for the trans-shipment process and to handle the increase in cargo.

Onwards from Afghanistan, to Central Asia and even to Eastern Europe, India can depend on the Uzbek high-speed railway track. Uzbekistan has developed an excellent but little utilised railway track for regular scheduled movement of high-speed freight trains from Tashkent (Uzbekistan) to Hairaton (Afghanistan). From Tashkent, in turn, there is excellent rail and road connectivity to the other Central Asian countries and onwards to Russia and Eastern Europe.

Strategically, use of a Nhava Sheva (or any other Indian port) – Chabahar – Hairaton – Tashkent route would also mean an alternative to China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ (OBOR) initiative in the region. It would undercut the potential of the Chinese-developed Gwadar port. Easily accessible from India’s western coast, Chabahar would be part of a larger India-supported transport corridor – the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC). The Indian-built, Zaranj (on the Iranian border) – Delaram (in Afghanistan’s Nimruz province) highway links up with Iran’s new connecting road from Zaranj down to Chabahar. In addition, India is involved in a rail link from Chabahar to Zahedan, on the Iran-Afghan border.

Chabahar port has not been popular among the Indian business community due to relatively weak logistical services & infrastructure and a lack of dissemination of proper information about the port. As a result, the objectives behind investing in the port have dimmed. To promote Chabahar, therefore, the government could consider giving rebate on transportation using this port. This rebate could be based on the notion of freight equalisation i.e. the freight charges incurred on sending a container (40 feet) from an Indian port, say Nhava Sheva, to Uzbekistan via Chabahar should not be higher than that via the Bandar Abbas route (currently, the freight from India to Uzbekistan amounts to around USD 5000.00). This would be a temporary measure for a few years, and could be discontinued once the traffic through Chabahar increases and its efficiency improves. It is quite probable that, over time, transportation of Indian exports and imports to and from the Central Asian states via Chabahar becomes considerably cheaper.

(Source: Chabahar: Gateway to Afghanistan and Central Asia, Brahma Chellaney, The Hindustan Times, April 26, 2018)

Besides promoting and incentivising the sea-road-rail routes, especially through the Iranian port of Chabahar, the other trading option for India that needs to be developed simultaneously, is the air route. Easy flight connectivity between India and the Central Asian countries and creating an Air Corridor, as with Afghanistan, would go a long way in promoting trade between India and the region and significantly enhance India’s outreach to Central Asia. Establishment of Air Corridors can be the quickest way to give impetus to India-Central Asia trade. The issue of supporting this in the initial period needs to be considered on lines similar to what has been attempted between India and Afghanistan. India along with USAID is providing a special tariff at the rate USD 0.50 per kg for transportation of commercial goods and weekly flights are arranged between India and a number of cities of Afghanistan. A special tariff of USD 1 per kg, for example, could be considered with respect to the Central Asian Republics.

It is important to work on both the Air Corridor and Chabahar fronts side-by-side as these are complementary in nature – high value goods would favour transhipment using the Air Corridor while bulk items can be transported through the sea-road/rail route. Tactically too this makes sense as it would lessen dependence on one mode/route and prevent it from turning into a potential choke point. Similarly, for Afghanistan an increase in trade through Chabahar would be beneficial as it would reduce its dependence on Pakistan with which it has had a difficult and uncertain relationship. A more upfront Afghanistan in expressing its interest and commitment to Chabahar would, therefore, be useful.

The Central Asian states could also be considered to be accorded preferential trade partner status. This would have a marked impact on trade volumes and India would be able to increasingly compete with China in a number of items in the region. For instance, a recent newspaper article mentioned that mining activity in Karim Nagar (Telangana) was getting adversely impacted due to the absence of Chinese buyers. Karim Nagar is known for Granite mining. Chinese companies purchase granite blocks from Khamam, Mattur (Parkasham), Ongal and other locations, and process the material from these blocks in China and then sell it in Central Asia, Europe and the U.S. Value addition in India in the case of such limited natural resources will also add to job opportunities locally besides enhancing trade. Besides granite, there are other minerals China buys from India, processes these cheaper and then sells in Central Asia and Russia at a competitive price.

In the meanwhile, till preferential/free trade deals are signed, extending trade privileges to the Central Asian Republics on a mutually beneficial basis could be considered. Such arrangements will act as a pushback against Chinese trade dominance in the region. Also, certain quotas applicable during imports, such as in the case of lentils need to be done away with. For instance, India imports green Moong dal from Uzbekistan, red lentil from Kazakhstan and yellow peas from Russia. Currently, these items can be imported only by large processors in India. These entities possessing DGFT issued import licences are generally not directly invested in the import process and work through agents. Removing such quotas would enhance competition by opening up the process benefiting the small and medium traders/entrepreneurs, who suffer in a quota-based trading system, as well as benefit the consumer.

Improved access to the region would also reduce distortions in trade to the benefit of all partners in the long run. For example, India is importing approximately 500 tons of Asafoetida, in which 450 metric ton approximately is imported from Afghanistan and 50 metric ton is imported from Iran, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan. Total net Asafoetida crop of Afghanistan was around 50 to 70 metric tons in 2019 and the rest 400 MT was imported by Afghanistan from Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and then imported by India from Afghanistan. For imports from Afghanistan, custom duty is free due to a preferential bilateral trade agreement (Zero duty is paid following issue of Afghanistan origin certificate). So, India is the main buyer of raw Asafoetida (Hing) from Central Asia. The average price is around USD 100 per kg and the total import is approximately 500 MT per year. The total value, therefore, comes to around USD fifty million (50,00,0000).

If a preferential trade status is accorded to the Central Asian Republics, then Central Asian origin goods will start coming directly to India in increased volumes, which will not only boost economic relations with the region but also add to revenue earned by Afghanistan, acting as a transportation hub. Similarly, Indian exports of tea, medicines, garments and engineering goods, spare parts will get a boost. With a trade agreement in place, we could also start competing for market share in new areas. For instance, China is the largest exporter of steel to Central Asia and Russia. While currently it is difficult for India to compete in this fairly large and growing market due to poor logistics and the levying of production cess and other taxes on steel, if duty drawback is permitted for steel exports to the Central Asian Republics, at least for five years, Indian steel products can also be expected to gain a significant market share in the region. Some form of restriction on exporting iron ore to China may also help.

An illustrative list of goods exported to the region from India is as follows:

- Pharmaceutical products

- Mechanical equipment

- Vehicle parts

- Optical instruments

- Surgical instruments

- Surgical accessories

- Refrigerator parts, including for assembling refrigerators in Uzbekistan

- Cosmetics

- Hair oil, Dry Mehndi powder

- Garments

- Fabric

- Marble Slabs

- Granite Slabs

- Chemicals

- Pesticides

- Insecticides

- Animal Feed Soya DOC (De-oiled Cake)

Imports from Central Asia:

- Asafoetida (Hing)

- Agricultural products

- Green Moong

- Yellow Peas

- Red lentils (Mansoor Dal)

- Kidney beans

- Chickpeas

- Liquorice roots

- Valeriana Wallichi (Tagara)

- Shilajit

- Honey

- Potash (India Imports 9 million tonnes annually, Uzbekistan is one of the largest producers)

- Hydrogen Gas

- Radio Active Elements

- Asbestos

- Precious metals

- Rare Earth metals

- Metal ores

- Ferrous/Non-Ferrous metal scrap

- Skin Hides Raw and Semi Processed

- Animal Guts

- Sheep Wool

- Industrial Chemicals

- Anthracite Coal (High Calorie Coal)

- Dry fruits

- Fresh fruits

- Silk yarn

There exists potential to procure a number of other products from the region, as per market demand. The Central Asian states can provide an alternative for sourcing some metallic and chemical products. For example, newspapers recently reported that Indian air conditioner manufactures have been facing difficulties as most of the components are imported from China, including Compressors and Copper Metallic Tubes, for which we are fully dependent on China. India can alternatively procure these items from Central Asia. Similarly, markets for export of Indian products not currently in the list can be explored. For instance, Indian tractors could gain a significant share in the Central Asian market. Today, India is the largest manufacturer of tractors followed by the U.S. and China and in 2018-19, exported around 90,000 tractors including to the U.S. and several African nations. (Ref: Tractor economics by Ashok Gulati and Ritika Juneja, The Indian Express, August 31, 2020)

Another area that has significant collaborative potential is in the exchange of technology and establishment of manufacturing in India. Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan have some quality engineering units that Indian industry could collaborate with. For instance, the Tungsten Alloy plant at Chirchik in Uzbekistan manufactures cemented carbide tools (cutting tools, precision tools) of high quality. Such companies could be encouraged to start a Joint Venture in India to manufacture the same. The raw material for the JV could be sourced from Uzbekistan initially and later extracted by recycling the JV’s products. Such JVs would also lower dependence on China for similar products.

As “CHAMP” (The USAID Commercial Horticulture and Agricultural Marketing Program) is promoting Indo-Afghan business, similarly a body/organization, in coordination with the MEA, can play an important role in promoting economic and cultural relations with the Central Asian countries. (Business-to-Business meetings are facilitated by CHAMP, supported by USAID and India. It also monitors progress of B2B meetings and tries to resolve outstanding issues between companies.)

In addition to trading activity, an area that has significant potential to further India-Central Asia ties is the already expanding sector of Medical Tourism. This again is similar to India’s ties with Afghanistan. There exists a big demand in the Central Asian region for specialised medical services that cities like Delhi and Mumbai can offer. Regular flights and visa facilitation for the purpose would help. In the medical domain, another segment to focus on would be collaboration in training. Indian medical teams could be sent to the region on a rotational basis. This would also benefit export of medical implants and accessories to the region from India. There exists a deep demand in the region for modern medical services that are affordable.

Of late, India has also seen a rapid growth in the number of private Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). This is another area that holds potential for collaboration with the Central Asian Republics. That two Indian HEIs - Amity University and Sharda University - already have a presence in Tashkent is a case in point.

Another collaborative activity that could be explored with renewed energy is that of film shooting. Central Asia is endowed with immense natural beauty and could provide interesting locales at reasonable cost for the dynamic Indian film industry. Tie-ups with various National Film Boards such as the Uzbekistan Film Commission to facilitate shooting of Indian films would be beneficial.

During the course of a renewed outreach, it would need to be kept in mind that the five Central Asian Republics differ significantly in socio-economic terms, and within a broad policy framework towards the region, India’s relations with each would have to be nurtured separately. Further, an understanding with Russia regarding the outreach/initiative would be useful. Geopolitically, among the Central Asian countries, Uzbekistan is of critical importance. With President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, the country has started playing a distinctly more open and active role in the region and internationally. Building economic links with Uzbekistan and the other Central Asian Republics would have strategic bearing, including on our ties with Afghanistan.

Way Forward:

- Issue directives to all Indian missions in Central Asia, Iran and Afghanistan to focus on facilitating and promoting trade/ transit trade and proactively help Indian businesspersons involved in trading with the Central Asian Republics. Organize Business-to-business meetings biannually at their locations.

- Similar directive to Customs in India with the advice to be mindful of any doubtful cargoes coming in given the past record of resort to smuggling.

- Engage the Turkmen government to ease transit of Indian goods travelling between the Iranian port of Bandar Abbas and other Central Asian countries and Russia through the Serakhs Check Post.

- Promote Chabahar as a port of preference to trade with Central Asia. Engage a suitable logistics firm to smoothen trade flow.

- Establish Air Corridors between Delhi, Mumbai and Amritsar and the region (Tashkent, Almaty, Dushanbe & Bishkek) at the earliest. All these sectors have had regular and chartered flights. A combination of air (for most products) and land-sea-land route (for bulk items such as polished Granite) would be optimal.

- Provide impetus to non-trading areas of economic cooperation such as medical tourism, medical training, higher education and film making.

- It would be ideal to coordinate India’s renewed economic outreach to Central Asia with Russia.

Dr Sunil Kumar & Pankaj Tripathi

***

Note: Based on a series of discussions with Indian businessperson Sunil Kumar, Director, Flamme Corporation.

Other references:

Chabahar: Gateway to Afghanistan and Central Asia, Brahma Chellaney, The Hindustan Times, April 26, 2018

Tractor economics by Ashok Gulati and Ritika Juneja, The Indian Express, August 31, 2020

Authors:

Dr Sunil Kumar, Director, Flamme Corporation

Pankaj Tripathi, ex-Civil Servant, Principal Consultant, Sarojini Damodaran Foundation