Indian Council of World Affairs

Sapru House, New DelhiPotential Of Financial Diversification Led By Brics

The growing discontent with the historical biases of the international financial institutions led the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) member countries to join hands based on the economic rationale of a more representative and inclusive financial decision-making order. This issue brief strives to first analyse the status-quo of the global financial system, potential of a BRICS common basket of currencies and efforts to diversify/ de-dollarise the financial world and finally look at contradictions and suggest actions needed to be undertaken by BRICS member states in order to achieve their stated objectives.

In the changing geopolitical global order, BRICS, which accounts for 24 per cent of world GDP and over 16 per cent of world trade,[i] is a centre point of discussion since the United States’ froze the reserve assets of the Russian Federation in February, 2022.[ii] This is primarily because the Russia-Ukraine crisis re-ignited a debate which was first envisioned in the 2010 BRICS Summit with respect to the risks associated with a single-dominant global reserve currency and lack of financial asset diversification.[iii] This has been an ongoing debate as even in the 2007–2008 global financial crisis,[iv] several countries openly discussed the necessity of reforming the international monetary system and called for the creation of “an international reserve currency that is disconnected from individual nations” because the prevailing system’s deficiencies were “caused by using credit-based national currencies.”[v] Living in a neo-liberal world order, the great power competition would to a great extent be intertwined with the financial and economic power potential of politically strong states.[vi]

STATUS QUO

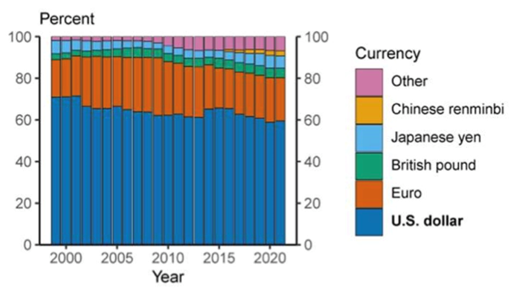

Despite recent efforts by countries like China[vii] to initiate swap lines, conduct trade in domestic currencies and diversify their reserve portfolios, it is a reality that we still live in a dollarised world. While the dollar’s share in reserve allocations has marginally reduced from about 70 per cent at the start of the century to 60 per cent at present,[viii] it is by far the most dominant and secure reserve currency which countries find safe to harbour during economic volatilities. The ‘Euro’ is a distant second with a near static rate of 20 per cent.[ix]

RESERVE ALLOCATIONS GRAPH (Source: BIS, 2019)[x]

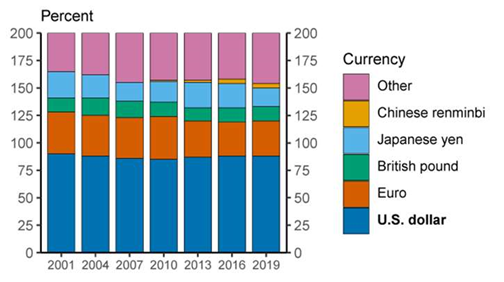

In the graph below, on a net-net basis at current exchange rates, percentages sum to 200 per cent because every Forex transaction includes two currencies. The graph makes it amply clear that the US dollar remains the single most invoiced currency, as at least one-side in almost every transaction is invoiced in the US dollar. As a result, every transaction between countries around the world is routed through New York and hence the exclusion from the US financial system is more potent than inclusion. This gives the US excessive jurisdictional reach to monitor and supervise trade flows.[xi] It is also interesting to note that the Chinese renminbi is 0 until 2007, and has marginally started rising since 2010 only.[xii]

INTERNATIONAL TRADE INVOICING GRAPH (Source: BIS 2019)[xiii]

POTENTIAL FOR DE-DOLLARIZATION

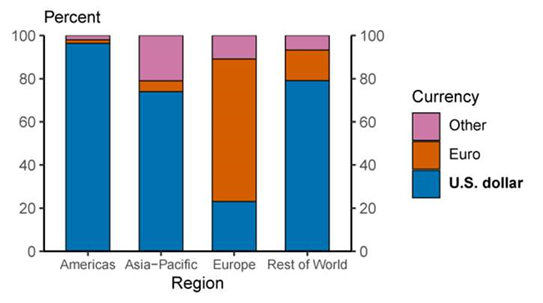

It is observed in the region-wise average mean of international trade graph below that there remains immense potential for de-dollarisation as proven by the European Union. The US $ extensively dominates every other region of the world except Europe because a common market exists which has significantly de-dollarised the continent.

Similarly, if the BRICS member states enter into bilateral/ multilateral arrangements amongst themselves, it would greatly shift the dynamics of the dollar dominated regions of the world. For instance, in Asia, such agreements would potentially harm the US $ which has a whopping 70 per cent invoicing rate in the region.[xiv] Similarly, joining of Brazil into a common currency basket mechanism would substantially alter the invoicing rate.[xv] The other substantial decline in the US $ hegemony can also stem from the fact that South Africa, being one of the most advanced countries of the African continent, would reduce the US $ invoicing to a great level in ‘Rest of World’ (Africa) column if the BRICS initiative becomes successful.[xvi]

REGION-WISE INTERNATIONAL TRADE INVOICING GRAPH 1992-2015

(SOURCE: FED, USA, 2021)[xvii]

WHY US DOMINATES?

The above graphs and data have made clear that there is major dominance of the US $ in region-wise trade invoicing and no real threat to the primacy of the US $ exists in the near future. However, we go on to study the reasons why the US $ is in such a position today and how, if ever, can BRICS emerge as an alternative dominant player in the financial sector. The deep, liquid and developed financial markets of the US allows it to continue injecting liquidity[xviii] in order to allow countries to run deficits essential for survival. The Triffin dilemma[xix] of getting caught into the trap of excessive liquidity and losing confidence makes sure that the central bank of USA, the Federal Reserve acts as an independent and autonomous body tasked with accommodating interests of various parts of the global economy. As a result, the US does benefit hugely from seignorage[xx], for eg: Seigniorage of producing a $100 bill is $99.804 as the cost of production is merely $0.196.[xxi] Nevertheless, this very independent nature of the central bank of the United States enthuses consumer confidence in the US $ unlike majorly state controlled banks like those in China or Russia.

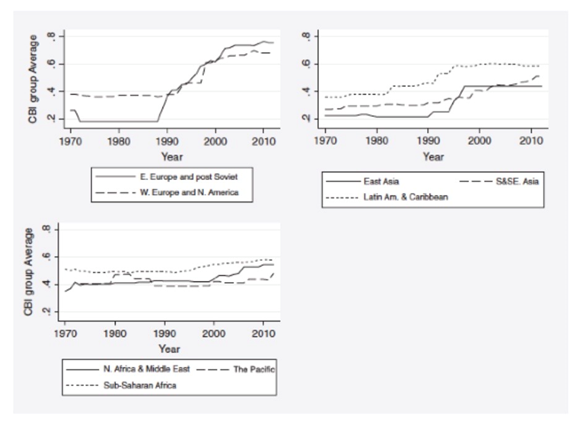

REGION WISE INDEPENDENCE OF CENTRAL BANKS (Source: Garriga 2016)[xxii]

Thus, the first step in order for any other currency to gain market confidence is to make sure the Central Bank of the said currency or organisation is largely autonomous and unbiased, having a commitment to low inflation and sustainable public debt.[xxiii] Ironically, on both these fronts, the US (along with majority of the world) is struggling.[xxiv] The checks and balances of the US system also induce trust in the system unlike an autocratic state where governance is totally centralised.[xxv] Last but not the least, today, the access to US financial system is vital to appeal of offshore dollar market because any rival framework is not even close to the value-size handled by US. For instance, Hong Kong (HSBC) handled a paltry 0.8 per cent of the amount Fedwire and CHIPS (Clearing House Interbank Payments System) handled per day in 2017 ($4.5 trillion).[xxvi] The graph above shows the region wise independence of banks with the developed world having by far more independent regulatory authorities.

RECENT EFFORTS

The most recent de-dollarisation milestone was achieved amid the COVID-19 pandemic at the BRICS 2020 Summit when BRICS agreed to reinforce and advance the current de-dollarisation processes.[xxvii] Under Russia’s chairmanship in 2020, the group jointly issued the Strategy for BRICS Economic Partnership 2025 which reiterated the members’ long-standing commitment to reforming the Bretton Woods institutions.[xxviii] More importantly, it identified several “priority areas of partnership” directly related to de-dollarisation, including: to promote the use of local currencies in mutual payments, to strengthen BRICS cooperation on payments systems, to collaborate on the development of new financial technologies, to advance the Credit Rating Agency mechanism, to continue cooperation on establishing the BRICS Local Currency Bond Fund, and to continue to facilitate the NDB in development financing while expanding the use of local currencies.[xxix] While India is currently working on its financial messaging system, it has further plans to link its UPI service with Russia’s System for Transfer of Financial Messages, which could possibly be linked with China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System. Once this is materialised, this linked system would cover most parts of the world.[xxx]

Scholars also grapple with the question whether the concerted coordination processes currently undertaken by Russia and China, triggered by their growing tensions with the United States, is only a temporary change, or whether it will lead to a broader paradigm shift in global finance.[xxxi] To give this context, the cumulative share of the US $ in China–Russia bilateral trade settlement fell from nearly 90 per cent in 2015 to 46 per cent in 2020.[xxxii] Moreover, China and Russia have launched their own cross-border payment mechanisms as an alternative to the US-dominated Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) network.[xxxiii] BRICS has also conceptualised a common BRICS Pay system for retail payments and transactions among member countries, which has been enabled by rapid progress in the financial technology (fintech) sector.[xxxiv] The biggest advantage of BRICS Pay is that this proposed integrated payment system would make possible the use of BRICS members’ national currencies as a direct basis of exchange for external payments.[xxxv] Currently, external settlements between BRICS members still require a conversion into the US $, which requires the engagement of US banks.[xxxvi]

BRICS has tried to simultaneously pursue both “go-it- alone” and “reform-the-status-quo” initiatives to increase the group’s influence.[xxxvii] For example, BRICS has established the NDB[xxxviii] (New Development Bank) with the objective of de-dollarising development finance. The group has also been planning the launch of a common payment framework that can be integrated with a BRICS digital currency called BRICS Coin.[xxxix]

For example, China has successfully launched the yuan oil futures contract- a financial instrument to diversify the global oil trade.[xl] BRICS has also collectively pursued reformist approaches, such as creating an alternative to the dollar-based Credit Rating Agency, advocating for the reform of the IMF Special Drawing Rights, and forming a BRICS stock exchanges alliance within the existing system.[xli]

According to the latest Bank for International Settlements Triennial Survey (2019), the Chinese renminbi was the eighth most actively traded currency, ranking just after the Swiss franc.[xlii] This is a significant increase from its ranking of 35th in 2001.[xliii] Additionally, the renminbi is now the most actively traded emerging market currency.[xliv] It reached 4.3 per cent of total global turnover in 2019, a significant rise compared with 0.1 per cent in 2004.[xlv] The Indian rupee was the second most traded BRICS currency, in 16th position worldwide and accounting for 1.7 per cent of global trade.[xlvi] The Russian ruble, Brazilian real, and South African rand were in 17th, 20th and 33rd position, respectively.[xlvii]

POTENTIAL FOR BRICS

The economic linkages of India and China- the large emerging Asian economies gives BRICS the biggest potential to collaborate as financial decisions of the major economies of the region have either always complemented each other or at least been in tandem.[xlviii] Given its immense potential, the BRICS currencies’ internationalisation can proceed in a variety of directions and spheres initially. The diversification of financial tools at its disposal can be initiated by issuing government bonds and private corporate bonds denominated in BRICS’ currencies.[xlix] BRICS could also open deposits in its currencies and develop their offshore centres as well. Initiating export-import settlements in home currencies as done by India while buying Iranian oil can also help reduce dollar invoicing.[l] Furthermore, steps must be initiated to start the accumulation of BRICS’ currencies in the official reserves of the rest of the world by inducing stability and making strategic investments such as direct or portfolio investments, providing loans in home currency etc. to financially distressed economies.[li] Concluding bilateral swaps with the central banks of other countries and establishing international financial funds in the BRICS’ currencies can also be pursued.[lii]

CHALLENGES

However, there are certain challenges which still would need to be considered before BRICS could actualise its own potential. The emerging BRICS infrastructure does not allow the member states to completely detach themselves from the existing US $-based financial system. These initiatives are predominantly happening at the sub-BRICS level and have not achieved the necessary economies of scale to present a coordinated challenge to the existing global financial system. A case in point being the use of local currency in India–Russia bilateral trade increased from 6 per cent to 30 per cent between 2013 and 2019, however, the same could not be replicated by BRICS.[liii]

There are two major constraints that prevent BRICS from forming a unitary coalition. First, some BRICS members have relatively closer relationships with the United States than with fellow BRICS members. To give some context, 86 per cent of India’s imports relied on the US $ invoicing despite only 5 per cent of India’s imports originating in the United States. Similarly, 86 per cent of India’s exports were invoiced in US $, while only 15 per cent of India’s exports were to the United States[liv]. While this prevents BRICS members from adopting a formal, cohesive de-dollarisation strategy in the near term, they may still informally pursue such initiatives.

Second, some BRICS members, such as Brazil and South Africa, are less likely to leave the US based financial system as they do not feel that they could be subjected to US sanctions in the near future and have economies that are more integrated into the dollar system than others. Thus, the BRICS members have neither group-level consensus nor do they seem to share the same sense of urgency to prioritise de-dollarisation. All of them are interested in reducing their dependence on the US $, but not all want to be separated from the US-led global financial system. Most BRICS members still hold large amounts of US $ assets in their reserves,[lv] so the weakening of the US $ imposes losses on them.

CONCLUSION

Despite all challenges, we do see a world where there is going to be significant push by the emerging markets to try and agree on a common minimum platform to reform the global financial system. From the Indian viewpoint, the pragmatic step forward is to gradually move into agreements with countries which would let India bypass/ circumvent western sanctions on such countries and India’s transactions, as a result, would not be disrupted. India was reported to have expressed interest in jointly exploring an alternative to SWIFT with Russia and China in order to conduct trade with countries under US sanction. But analysing the current global volatilities and India’s position of non-alignment and acting in self-interest, the potential gains must in itself not be seen as a reason for India to detach itself from the current financial institutional mechanism of the global economy, especially when India does maintain good relations with the western countries. Therefore, the economics of diversification should hint towards countries like China to re-analyse its foreign policy with respect to India as having India at loggerheads does not augur well for the Chinese ambitions of world hegemony itself.

Nonetheless, ending on a positive note with what India has been doing right and should continue taking such small steps in order to act in self- interest- we could safely say that BRICS’ efforts toward de-dollarisation in international trade have progressed. A case in point would be countries like Argentina expressing sincere willingness to join the bloc!

*****

* Jaiveer Singh, Research Intern, Indian Council of World Affairs, Sapru House, New Delhi.

Disclaimer: The views are of the author.

Endnotes

[i] BRICS. http://infobrics.org. Accessed on 13th September, 2022.

[ii] New York Times (February 28, 2022), US Escalates Sanctions with a Freeze on Russian Central Bank Assets. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/28/us/politics/us-sanctions-russia-central-bank.html. Accessed on 12th September, 2022.

[iii] MEA, GOI (April 16,2010), II BRIC SUMMIT-Joint Statement. https://mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/3983/II+BRIC+SUMMIT++Joint+Statement. Accessed on 21st August, 2022.

[iv] UNCTAD (December 2010), Financial and Economic Crisis of 2008-2009 and Developing Countries. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/gdsmdp20101_en.pdf. Accessed on 20th August, 2022.

[v] Zhou, X. (March 23, 2009). Reform the International Monetary System. www.bis.org/review/r090402c.pdf. Accessed on 22nd August, 2022.

[vi] Oxford University (January, 2013). https://www.qeh.ox.ac.uk/publications/understanding-international-diplomacy-theory-practice-and-ethics. Accessed on 19th August, 2022.

[vii] Atlantic Council (March 18, 2022), Internationalization of the Renmibi via bilateral swap lines. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/econographics/internationalization-of-the-renmibi-via-bilateral-swap-lines/. Accessed on 1st September, 2022.

[viii] BIS (2019), Annual Report. https://www.bis.org/about/areport/areport2020.pdf. Accessed on 2nd September, 2022.

[ix] BIS (2019), Annual Report. https://www.bis.org/about/areport/areport2020.pdf. Accessed on 2nd September, 2022.

[x] BIS (2019), Annual Report. https://www.bis.org/about/areport/areport2020.pdf. Accessed on 2nd September, 2022.

[xi] BIS (2019), Annual Report. https://www.bis.org/about/areport/areport2020.pdf. Accessed on 2nd September, 2022.

[xii] BIS (2019), Annual Report. https://www.bis.org/about/areport/areport2020.pdf. Accessed on 2nd September, 2022.

[xiii] BIS (2019), Annual Report. https://www.bis.org/about/areport/areport2020.pdf. Accessed on 2nd September, 2022.

[xiv] BIS (2019), Annual Report. https://www.bis.org/about/areport/areport2020.pdf. Accessed on 2nd September, 2022.

[xv] BIS (2019), Annual Report. https://www.bis.org/about/areport/areport2020.pdf. Accessed on 2nd September, 2022.

[xvi] FED (October 06, 2021), The International Role of the US $. https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/the-international-role-of-the-u-s-dollar-20211006.html. Accessed on 5th September, 2022.

[xvii] FED (October 06, 2021), The International Role of the US $. https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/the-international-role-of-the-u-s-dollar-20211006.html. Accessed on 5th September, 2022.

[xviii] Federal Reserve, US (March 05, 2007), Liquidity: ability to be transformed into another asset without loss of value. https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/warsh20070305a.htm. Accessed on 8th September, 2022.

[xix] IMF (November, 1960), Triffin Dillemma: If the United States stopped running balance of payments deficits, the international community would lose its largest source of additions to reserves. The resulting shortage of liquidity could pull the world economy into a contractionary spiral, leading to instability. https://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/center/mm/eng/mm_sc_03.htm. Accessed on 8th September, 2022.

[xx] IMF (December 31, 2016), Seigniorage: The difference between the value of currency/money and the cost of producing it. It is essentially the profit earned by the government by printing currency. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/The-Political-Economy-of-Seigniorage-18513. Accessed on 8th September, 2022.

[xxi] Joseph H. Haslag (1998), Seigniorage Revenue and Monetary Policy. https://www.dallasfed.org/~/media/documents/research/er/1998/er9803b.pdf. Accessed on 25th August,2022

[xxii] Ideas (2016), Central Bank Independence in the World. https://ideas.repec.org/a/taf/ginixx/v42y2016i5p849-868.html. Accessed on 10th September, 2022.

[xxiii] Ideas (2016), Central Bank Independence in the World. https://ideas.repec.org/a/taf/ginixx/v42y2016i5p849-868.html. Accessed on 10th September, 2022.

[xxiv] Forbes (February 16, 2022), US National Debt Surpasses $30 Trillion: What This Means For You. https://www.forbes.com/advisor/personal-finance/u-s-national-debt-surpasses-30-trillion-what-this-means-for-you/. Accessed on 8th September, 2022.

[xxv] Princeton (October 10, 2017), The Power and Independence of the Federal Reserve. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691178387/the-power-and-independence-of-the-federal-reserve. Accessed on 9th September, 2022.

[xxvi] The Federal Reserve (July 25, 2022), Fedwire Funds Service- Monthly Statistics. https://www.frbservices.org/resources/financial-services/wires/volume-value-stats/monthly-stats.html. Accessed on 25th August, 2022.

[xxvii] BRICS (2020), Strategy for BRICS Economic Partnership 2025. https://eng.brics-russia2020.ru/images/114/81/1148155.pdf. Accessed on 29th August, 2022.

[xxviii] BRICS (2020), Strategy for BRICS Economic Partnership 2025. https://eng.brics-russia2020.ru/images/114/81/1148155.pdf. Accessed on 29th August, 2022.

[xxix] BRICS (2020), Strategy for BRICS Economic Partnership 2025. https://eng.brics-russia2020.ru/images/114/81/1148155.pdf. Accessed on 29th August, 2022.

[xxx] J. Hillman (2020), China and Russia: Economic Unequals. Center for Strategic & International Studies Report. Google Scholar. Accessed on 28th August, 2022.

[xxxi] Hal Brands and Michael Beckley (September 24, 2021), China Is a Declining Power- and That’s the Problem. https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/09/24/china-great-power-united-states/. Foreign Policy. Accessed on 12th September, 2022.

[xxxii] Simes, D. (August 6, 2020). China and Russia ditch dollar in move toward “financial alliance.” Nikkei Asia. https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/China-and-Russia-ditch-dollar-in-move-toward-financial-alliance. Accessed on 26th August, 2022.

[xxxiii] Business Insider (April 29, 2022), China and Russia are working on homegrown alternatives to the SWIFT payment system. https://www.businessinsider.in/politics/world/news/china-and-russia-are-working-on-homegrown-alternatives-to-the-swift-payment-system-heres-what-they-would-mean-for-the-us-dollar-/articleshow/91168432.cms. Accessed on 13th September, 2022.

[xxxiv] East Asia Forum (July 4, 2022), BRICS Pay. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/tag/brics-pay/. Accessed on 11th September, 2022.

[xxxv] East Asia Forum (July 4, 2022), BRICS Pay. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/tag/brics-pay/. Accessed on 11th September, 2022.

[xxxvi] BRICS India. (2021), Evolution of BRICS. https://brics2021.gov.in/about-brics. Accessed on 26th August, 2022.

[xxxvii] Liu, Zongyuan Zoe and Mihaela Papa (February 24, 2022) Can BRICS De-Dollarize the Global Financial System? https://www.cambridge.org/core/elements/can-brics-dedollarize-the-global-financial-system/0AEF98D2F232072409E9556620AE09B0. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022. Ch. 4. Accessed on 28th August, 2022.

[xxxviii] NDB (July, 2022). https://www.ndb.int. Accessed on 11th September, 2022.

[xxxix] Forbes (August 16, 2022), Follow the Yellow BRIC Road to a New Digital Reserve Currency. https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidbirch/2022/08/16/follow-the-yellow-bric-road-to-a-new-digital-reserve-currency/. Accessed on 10th September, 2022.

[xl] Financial Times (February 1, 2021), China oil futures hit record levels. https://www.ft.com/content/877b3676-5236-4d90-bfbc-b0683faa5af8. Accessed on 10th September, 2022.

[xli] BU Global Development Policy Center (October 26, 2021), The BRICS and the Financing Mechanisms They Created. https://www.bu.edu/gdp/2021/10/26/the-brics-and-the-financing-mechanisms-they-created-progress-and-shortcomings/. Accessed on 7th September, 2022.

[xlii] Bank for International Settlements (2019), Triennial Central Bank Survey of Foreign Exchange and Over-the-Counter (OTC) Derivatives Markets in 2019. www.bis.org/statistics/derstats.htm. Accessed on 25th August, 2022.

[xliii] Bank for International Settlements (2019), Triennial Central Bank Survey of Foreign Exchange and Over-the-Counter (OTC) Derivatives Markets in 2019. www.bis.org/statistics/derstats.htm. Accessed on 25th August, 2022.

[xliv] Bank for International Settlements (2019), Triennial Central Bank Survey of Foreign Exchange and Over-the-Counter (OTC) Derivatives Markets in 2019. www.bis.org/statistics/derstats.htm. Accessed on 25th August, 2022.

[xlv] Bank for International Settlements (2019), Triennial Central Bank Survey of Foreign Exchange and Over-the-Counter (OTC) Derivatives Markets in 2019. www.bis.org/statistics/derstats.htm. Accessed on 25th August, 2022.

[xlvi] Bank for International Settlements (2019), Triennial Central Bank Survey of Foreign Exchange and Over-the-Counter (OTC) Derivatives Markets in 2019. www.bis.org/statistics/derstats.htm. Accessed on 25th August, 2022.

[xlvii] Bank for International Settlements (2019), Triennial Central Bank Survey of Foreign Exchange and Over-the-Counter (OTC) Derivatives Markets in 2019. www.bis.org/statistics/derstats.htm. Accessed on 25th August, 2022.

[xlviii] Bloomberg (August 11, 2015), China Rattles Markets with Yuan Devaluation. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-08-11/china-weakens-yuan-reference-rate-by-record-1-9-amid-slowdown. Accessed on 28th August, 2022.

[xlix] Liu, Zongyuan Zoe and Mihaela Papa (February 24, 2022) Can BRICS De-Dollarize the Global Financial System? https://www.cambridge.org/core/elements/can-brics-dedollarize-the-global-financial-system/0AEF98D2F232072409E9556620AE09B0. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022. Ch. 5. Accessed on 28th August, 2022.

[l] Liu, Zongyuan Zoe and Mihaela Papa (February 24, 2022) Can BRICS De-Dollarize the Global Financial System? https://www.cambridge.org/core/elements/can-brics-dedollarize-the-global-financial-system/0AEF98D2F232072409E9556620AE09B0. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022. Ch. 5. Accessed on 28th August, 2022.

[li] Liu, Zongyuan Zoe and Mihaela Papa (February 24, 2022) Can BRICS De-Dollarize the Global Financial System? https://www.cambridge.org/core/elements/can-brics-dedollarize-the-global-financial-system/0AEF98D2F232072409E9556620AE09B0. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022. Ch. 5. Accessed on 28th August, 2022.

[lii] Liu, Zongyuan Zoe and Mihaela Papa (February 24, 2022) Can BRICS De-Dollarize the Global Financial System? https://www.cambridge.org/core/elements/can-brics-dedollarize-the-global-financial-system/0AEF98D2F232072409E9556620AE09B0. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022. Ch. 5. Accessed on 28th August, 2022.

[liii] D.R. Chaudhury and M. Pubby (August 30, 2019). Narendra Modi: Bilateral Trade in Rupee-Rouble Up 5-Fold during Modi Govt. The Economic Times.Google Scholar. Accessed on 29th August, 2022.

[liv] Gopinath et al. (August, 2017), Dollar Pricing Redux. https://www.bis.org/publ/work653.pdf. Accessed on 29th August, 2022.

[lv] IMF (June 30, 2022), Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves. (https://data.imf.org/?sk=E6A5F467-C14B-4AA8-9F6D-5A09EC4E62A4. Accessed on 13th September, 2022.