Indian Council of World Affairs

Sapru House, New DelhiOffshore Asylum Processing: UK-Rwanda Plan

The UK Parliament passed on 22nd April 2024 the controversial UK-Rwanda Plan for which the Home Office has allegedly spent over £20m setting up the Rwanda scheme.[i] Irregular migration has become a recurring headline in UK politics, especially with the looming general election. The Rwanda Plan has stirred UK politics and survived the tenure of three Prime Ministers – Boris Johnson, Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak. Under the Plan, migrants reaching the UK through irregular means on small boats will be deported to Rwanda for further proceeding on their application. The Plan has faced scrutiny for being perceived as an effort by the UK to ‘offshore’ its asylum responsibilities, marking a new phase in Britain’s stance on migration governance.

This Special Report details the timeline, related developments, and associated costs of the Rwanda Plan. It also discusses the Plan’s overarching implications for immigration and asylum governance.

RECENT IMMIGRATION RECORDS IN THE UK:

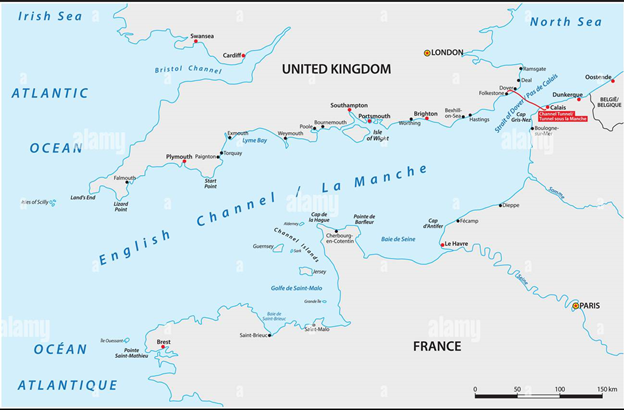

Irregular migration has become a key focus area in the UK's domestic and foreign policy. It comprises irregular entry channels, i.e., mediums not authorised by the state as regular under immigration laws and regulations. Commonly reported irregular migration methods include entry by hiding in containers, hiding under or in lorries, or crossing the English Channel in a small boat without carrying valid travel documents. The Home Office data finds that in 2023, there were 36,704 irregular entries into the UK, representing a 33% decrease from the previous year. Of these, 80% arrived via small boats.[ii] The UK Home Office reports a rising trend of irregular migration on ‘small boats’ traversing the English Channel (see Figure 1).

This Special Report looks at how the UK deals with ‘small boats’ migration, which it condones as an irregular medium of entry to the UK. Small boats refer to the vessels on which the crossings are made. They are mostly inflatable boats, dinghies, or kayaks that are not well-suited for the long journey and are not sturdy.

Figure 1: Map of English Channel[iii]

Irregular entry via small boats is the most visible and tends to be more consistently recorded. However, this method of irregular entry is relatively recent, with government records documenting it over the last twenty years. Small boats entry have dramatically increased after 2018, with the Covid-19 pandemic playing a pivotal role. Recent statistics from the Home Office reveal that in 2022, 45,755 individuals arrived in the UK via small boats crossing the English Channel.[iv] Comparatively, in the first six months of 2023, there was a 10% decrease in such arrivals, with 11,434 people crossing the Channel. A small number of nationalities make up behind these ‘small boat’ numbers, including Iranian (21%), Albanian (15%), Iraqi (15%), Afghan (13%), or Syrian (7%).[v]

Studies also reveal seasonal fluctuations in these numbers and thus, do not reflect a sustained pattern. UK-based migration experts argue that the available data also does not explain why migrants embark on such life-threatening journeys. A combination of reasons can be attributed to the rise of small boat migration, including the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted other routes and led to the prominence of small boats as an alternative means facilitated by networks of human smugglers.[vi] Many are also drawn to the UK as they have kinship ties and language familiarity. ‘Missing Migrants Project’ published by the International Organization for Migration notes that since 2014, over 240 migrants have either died or disappeared while trying to cross the English Channel.[vii]

The ruling Conservative party pledged “to stop the boats,” which comes with the reasoning that most individuals who arrive in Britain on small boats seek international protection by applying for asylum in the UK. Many of these individuals are subsequently recognised as refugees and granted permission to settle in Britain. Data noted by the Migration Observatory based at Oxford states that around 92% of overall small boat arrivals have claimed asylum in the UK or were named as dependent on an application.[viii] These numbers have further affected an already distressed asylum system in the UK. However, it is interesting to note that the UK currently hosts approx. 1% of the 27.1 million refugees whichwere forcibly displaced worldwide.[ix]

Figure 2: Comparision between ‘small boats’ arrival and asylum applications[x]

Small boat migration has increasingly become a major irritant in the bilateral relationship between the UK and France, considering that most of these journeys happen on France’s north coast. Both governments have signed a series of bilateral agreements over the issue. However, tensions between the UK and France further escalated with the drowning of 27 migrants from Africa and West Asia while crossing the English Channel in November 2021.[xi][xii]

Domestically, there are also dramatic steps taken by the UK government to address the issue, starting with the Brexit Referendum 2016 and the recent UK Rwanda Plan in 2022, which specifically targets irregular migration via ‘small boats’. This was followed by the introduction of the Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Bill in 2023, which has now been passed by the Parliament. The same year, PM Sunak made ‘stop the boats’ a cornerstone of his five-point strategy to enhance the country's overall economic well-being.[xiii]

UK-RWANDA RELATIONS:

UK and Rwanda share a long history of mutual partnership. In 2009, Rwanda became the second country without historical ties to the UK to join the Commonwealth. However, with the Rwanda Plan, the UK has taken the geo-political ties to a new level. Partnerships between the countries have now gone beyond regular development aid and economic growth support. Critics point out that the Rwanda Plan can be seen as a continuation of the UK's international engagement but with a significant shift towards offloading responsibilities traditionally managed within its borders.[xiv]

For Rwanda, such a relocation policy is not new. Previously, it had a similar arrangement with Israel from 2013 to 2018, whereby Israel began sending Eritrean and Sudanese nationals seeking asylum to Rwanda.[xv]

UK- RWANDA PLAN: A TIMELINE

The UK-Rwanda Plan was initially unveiled by former Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government, known as the Migration and Economic Development Partnership (MEDP), with the Government of Rwanda on 14th April 2022 in Parliament. The MEDP included a five-year ‘asylum partnership arrangement’ detailed in a non-binding memorandum of understanding (MoU). MEDP was later re-named as the UK-Rwanda Asylum Partnership. However, the UK Supreme Court declared the Rwanda Plan unlawful in 2023. Subsequently, under the Sunak Government, the two governments signed the UK-Rwanda Asylum Partnership Treaty on December 5, 2023, and the UK Government proposed the Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Bill on December 6, 2023, to further cement the Rwanda Plan (refer to Table 1 for the timeline).[xvi]

The Rwanda Plan 1.0:

“Our new Migration and Economic Development Partnership will mean that anyone entering the UK illegally – as well as those who have arrived illegally since January 1st (2022) – may now be relocated to Rwanda”.[xvii]

- Boris Johnson, Former UK Prime Minister statement introducing the MEDP, subsequently known as the UK-Rwanda Plan ( April, 2022)

The Rwanda Plan targets migrants who enter the UK unlawfully. As described above, small boats are an increasing contributor to the numbers. Therefore, the UK-Rwanda plan aims to act as a deterrence to the problem of increasing small boats. Under the Plan, as stated, “those who have their asylum claim deemed as inadmissible and have made a dangerous and illegal journey to the UK since 1 January 2022 may be relocated to Rwanda for processing under the asylum system of that country.”[xviii] Rwandan national and unaccompanied asylum-seeking children would not be relocated.

Asylum claims of individuals moved to Rwanda will be evaluated in Rwanda, and those granted refugee status there will not have the option to return to the UK.[xix] Unsuccessful applicants would be asked to depart voluntarily or gain another kind of migratory status (such as economic migrant) in Rwanda and will be given equal treatment to those recognised as refugees. The final decision on those deported to Rwanda from the UK will depend on the Rwandan government.[xx]

Former PM Johnson indicated that Rwanda, a member of the Commonwealth, could potentially host "tens of thousands" of these migrants, affirming that Rwanda is a safe haven for migrants (regardless of their status).[xxi]

Reactions:

The UK-Rwanda Plan elicited mixed responses, highlighting deep divisions within the ruling Conservative Party and the more extensive UK political system regarding migration policies. This Plan emerged against the backdrop of crises in Ukraine and Afghanistan, during which the UK introduced several initiatives, such as the Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme (ACRS) and Homes for Ukraine in 2022, demonstrating the nation's and its citizens' willingness to welcome refugees. These efforts were widely regarded as examples of the UK's hospitality and generosity. However, similar plans of refugee resettlement for other nationalities remain severely limited.

The Rwanda Plan garnered severe criticism from Opposition parties, legal agencies, civil society organisations and international organisations working for the rights of migrants and refugees alike. These entities have quoted the Plan not only to be a “national scandal” and “cruel” but also “unlawful” towards migrants.[xxii] UNHCR (UN’s principal refugee agency) stated that the agreement is ‘incompatible with the letter and spirit of the 1951 Convention’. The UK is a signatory of the 1951 Refugee Convention and, hence, cannot restrict migrants from applying for asylum in any country of their choosing. The Convention forbids the punishment of migrants due to their method of entering a country, indicating that the medium of travel to the UK should not influence their asylum application.[xxiii]

Questioning whether the Rwanda Plan will act as a successful deterrent and reduce irregular entry also comes with the moral and ethical responsibility of the UK to provide refuge. The Refugee Council UK argues that the majority of individuals crossing the Channel—many of whom are women and children—would likely qualify for refugee status in the UK once their asylum applications are assessed.[xxiv]

Human rights defenders based in Rwanda questioned the sanctity of this Plan. Writing in the Guardian, a Rwandan opposition leader explained the tangible evidence of a lack of respect for human rights in Rwanda.[xxv]

Nonetheless, the UK government's strong endorsement of the Rwanda Plan and its firm stance on stopping boat crossings has sustained these criticisms. The Home Office's support for the plan was framed around the government's dedication to preventing dangerous crossings and the exploitation of migrants by criminal networks. The Rwanda Plan is portrayed as a crucial element of the government’s strategy to break the cycle of irregular migration, disrupt the operations of criminal networks and human smuggling, and reduce the risk of deaths during such perilous sea journeys. The contrasting approaches to handling different groups of refugees and immigrants in Britain have sparked a debate on the consistency and ethics of the UK's migration policies.

The Rwanda Plan Declared ‘Unlawful’:

Despite the plan's strong reactions, the UK Government was keen on sending its first flight taking asylum seekers to Rwanda on 14 June 2022. This flight was cancelled due to an injunction issued by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), of which the UK is a member. A ruling by the Strasbourg Court on one of the seven asylum cases allowed lawyers for the other six cases to make successful appeals suspending their removal to Rwanda. This initial legal victory prompted the lawfulness of the overall policy to be challenged in the UK High Court by asylum seekers who were bound for relocation. The High Court ruling on 19th December 2022 ruled in favour of the Plan. However, this decision was appealed to the Court of Appeal in June 2023, where, with a majority of 2 judges, the policy was declared unlawful[xxvi].

The Home Office appealed this judgement to the UK Supreme Court, which unanimously declared the Plan as ‘unlawful’ on 15th November 2023 as it did not concur with the principle of non-refoulement and put migrants at risk of being persecuted. Robert Reed, President of the Supreme Court, noted that the judgement should not be seen as a political statement and should be based purely on UK law, but also owing to principles embedded in the ECHR.[xxvii]

The Supreme Court identified three primary concerns in sending migrants ( who are potential asylum seekers) to Rwanda[xxviii]:

- Rwanda’s record on human rights

- Significant and widespread flaws in Rwanda’s asylum evaluation process

- Instances under a previous arrangement with Israel where Rwanda deported asylum seekers back to their home countries, breaching the principle of nonrefoulement

Several migrant rights organisations, politicians, and migrant groups welcomed the Supreme Court decision. Steve Smith, head of refugee charity Care4Calais and a claimant in the case, remarked that the judgment was “a victory for humanity.” The decision also heightened tensions within the ruling party, wherein some Conservative leaders called for a revised version with more strict deportation rules. In contrast, other Tory leaders prompted a fresh perspective on the issue.[xxix]

The Rwanda Plan 2.0: Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Bill, 2023

“I am unable to make a statement that in my view, the provisions of the Safety of Rwanda ( Asylum and Immigration) Bill are compatible with the Convention Rights, but the Government nevertheless wishes the House to proceed with the Bill.”[xxx]

- Home Secretary James Cleverly (on the first page of the proposed newly passed Rwanda Bill)

In quick response to the decision of the Supreme Court and recognising its bold commitments to ‘stop the boats’, the Sunak Government swiftly signed the UK-Rwanda Asylum Partnership Treaty on 5th December 2023, replacing the earlier signed Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Rwanda. Additionally, to cement this bilateral agreement and directly respond to the Supreme Court’s concerns over the safety of Rwanda to protect migrants and asylum-seekers, the Government introduced the Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Bill on 7th December 2023. For the past few months, the Bill has seen several heated discussions and amendments in the Lower and Upper House of the UK Parliament. The Bill has been finally passed by the Parliament on 22nd April 2024. The law enables the Parliament to confirm the status of the Republic of Rwanda as a safe third country, thereby ensuring the removal of persons who arrive in the United Kingdom (UK) under the Immigration Acts (Illegal Migration Act 2023, Nationality and Borders Act 2022).

The revised versions of the Rwanda Plan garnered even stronger reactions. Some migration experts see it as the government’s hasty decision over offshoring asylum processes that may have far more serious legal, geopolitical and human rights ramifications. In Parliamentary debates, the Moderate Conservative MPs remarked that they would withdraw support if the Bill breached Britain’s human rights obligations. A significant reaction also included the resignation of the Immigration Minister, Robert Jenrick, who had pressed for more strict measures.[xxxi]

|

Key Date |

Key Events in the Legislative Journey of the Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Bill |

|

November, 2021 |

Nationality and Borders Bill introduced: the Bill made crossings to Britain through irregular means a criminal offence. The Bill also gave concerned authorities scope to make arrests and remove asylum seekers. |

|

13-14 April-22 |

Migration and Economic Development Partnership (MEDP) signed with the Government of Rwanda. The then Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, announced the Rwanda Plan in a speech the following day. |

|

April, 2022 |

Nationality and Borders Bill passed by the Parliament. |

|

June, 2022 |

First deportation flight to Rwanda halted by an interim decision of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) |

|

March, 2023 |

Illegal Migration Bill introduced strengthening government’s support towards the Rwanda Plan. The Bill puts strict measures to deal with small boat crossings. It became a law in the same year in July. |

|

15-Nov-23 |

The Rwanda Plan is declared ‘unlawful’ by the UK Supreme Court. |

|

05-Dec-23 |

Home Secretary, James Cleverly signs the UK-Rwanda Asylum Partnership Treaty in Kigali, replacing the earlier MEDP MoU. |

|

07-Dec-23 |

Introduction of the Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Bill in the House of Commons. |

|

29-Jan-24 |

Second reading: Full debate on the key principles of the Bill in the House of Commons. |

|

12, 14, 19 February 2024 |

Committee stage: Line-by-line examination of the Bill during these dates. |

|

4, 6 March 2024 |

Report stage: Detailed scrutiny of the Bill, including discussions on amendments. |

|

12-Mar-24 |

Third reading: Members make final small changes to refine the bill, ensuring its effectiveness, before it is passed from the House of Commons to the House of Lords. |

|

18 January - 12 March 2024 |

The bill was considered by the House of Lords before returning to the House of Commons in the parliamentary 'ping pong' process. |

|

20-Mar-24 |

House of Lords considered changes made by the Commons. Amendments discussed included regard for domestic and international law, implementation of the Rwanda Treaty, decisions on individual claims and appeals, age assessments for unaccompanied children, removal of victims of modern slavery and human trafficking, and exemptions for UK armed forces personnel overseas. |

|

15-16th Apr-24 |

The Bill returns to the House of Commons to further consider House of Lords suggested amendments. |

|

22-Apr-24 |

The Safety of Rwanda(Asylum and Immigration) Bill is passed by the UK Parliament. |

Table: Timeline of the UK-Rwanda Plan[xxxii]

How is the new Plan different?

The UK-Rwanda Treaty has now been ratified as the Safety of Rwanda Act per the Royal Assent given on 24th April 2024. The Treaty is described as a “pilot” or “trial” and will last until 13th April, 2027 with with the possibility of extension. Here are the key differences from the earlier signed MoU (Migration and Economic Development Partnership (MEDP ) with Rwanda[xxxiii]:

- Legally Binding Commitments: Unlike the original MoU, the revised Treaty is legally binding, providing stronger assurances that refugees will not be removed from Rwanda in violation of the agreement.

- Permanent Residence for Non-Asylees: The Treaty stipulates that individuals who do not qualify for asylum will be granted permanent residence permits in Rwanda under Article 10, a provision not included in the original MoU which allowed for the potential removal of people denied asylum.

- New Asylum Decision Institutions: Annex B of the Treaty establishes new bodies to handle asylum applications and appeals, featuring non-Rwandan judges and mandatory consultation with independent experts, enhancing procedural safeguards beyond those in the original MoU.

- Expanded Repatriation Conditions: Article 11 of the Treaty allows the UK to request the return of relocated individuals from Rwanda for any reason, expanding upon the original MoU, which only allowed returns, if legally required.

- Enhanced Monitoring Powers: Under the Treaty, the independent Monitoring Committee has greater autonomy in setting its terms of reference, publishing inspection reports, establishing a complaints system, and hiring staff—capabilities not permitted by the UK’s immigration inspectorate.

- Non-Discrimination Clause: Article 3 of the Treaty specifies that the rights of the relocated apply regardless of nationality and without discrimination, addressing concerns raised by the UK Supreme Court regarding the treatment of Middle Eastern asylum seekers in Rwanda.

- Dispute Resolution Mechanism: Article 22 of the Treaty introduces an arbitration mechanism for resolving disputes between the UK and Rwanda, a feature explicitly ruled out in the MoU.

The Treaty additionally outlines that certain groups, such as unaccompanied minors, will not be subject to transfer under its terms. While the relocation of families with children is theoretically possible under the Treaty, the Home Office has indicated that it does not plan to transfer families at the outset. Additionally, Rwandan asylum seekers already present in the UK are not included in the relocation agreement.

A dual-layered approach:

The Home Office noted that decisions on the suitability of relocation to Rwanda and whether Rwanda itself can be deemed a safe destination for asylum seekers should be made on a case-by-case basis. This involves two levels of safety assessments before any transfer is made[xxxiv]:

- General Objective Test: The UK, as the country considering the transfer, has a foundational responsibility to conduct a thorough and current evaluation of conditions in Rwanda to ensure that it meets the safety criteria for receiving asylum seekers.

- Individualised Test: In addition to the general assessment, each asylum seeker must be given the chance to present their circumstances that could prove Rwanda unsafe specifically for them.

This two-tiered approach suggests that the Home Office is attempting to balance its obligations under the principle of non-refoulment under international law—i.e., not sending asylum seekers to a place where they would be in danger. The first test ensures Rwanda, as a state, is generally capable and willing to protect the human rights of those sent there. The second test acknowledges the unique risks that individuals might face, which a broad-stroke assessment cannot capture.

Why is there a persistent need, and how much does the Rwanda Plan cost?

Presenting the revised Rwanda Plan, former Home Secretary Suella Braverman remarked that the current asylum system is broken and needs to be fixed. She detailed that the current number of irregular arrivals has overwhelmed the asylum system, with the backlog running over 160,000. The current asylum system has severe financial costs, estimated at around £3 billion annually for British taxpayers.[xxxv]

However, like any other border externalisation border policy, the Rwanda Plan comes with its financial cost. The real overall costs of the Plan remain unknown. Public sources reveal that the UK paid Rwanda £140 million in the deal's first year in 2022. Over £20 million was an advance payment for initial set-up costs for the asylum partnership agreement.[xxxvi] The UK is responsible for the accommodation and asylum processing costs of each person transferred, plus an additional five-year integration package for those granted asylum in Rwanda. The tentative amount is comparable to the UK’s domestic asylum processing costs, which were approximately £12,000 per person in 2022.[xxxvii]

Beyond these per-person expenses, the UK covers costs for initial screening, casework, legal aid, and expenses from legal challenges and travel costs. The Home Office’s estimate to transfer a person to a safe third country like Rwanda is £169,000—significantly higher than the £106,000 estimated for processing an asylum claim within the UK. These figures have been scrutinised for their underlying assumptions.[xxxviii]

Implications of the Rwanda Plan: What does the Plan mean for immigration and aslyum governance?

Migration experts are doubting the Rwanda Plan's real versus projected impact on reducing irregular migration.[xxxix] The controversial Plan may have set a wrong precedent for migration governance in the following ways:

a. Externalisation of asylum responsibilities:

This Special Report explains the complex journey of the Rwanda Plan. Apart from the major legal dilemmas it raises, the Plan also prompts an inquiry into states' moral and ethical responsibility in dealing with migration. Can states undertake extraterritorial measures without compromising international and domestic law? To what extent do these policies protect the right to asylum and refugee?

The international scrutiny that the Rwanda Plan has so far received reveals that it is an externalisation of asylum responsibilities because it represents a shift in the UK's approach to managing asylum seekers. Rather than processing asylum claims within its borders, the UK has taken an extraordinary measure of delegating this responsibility to Rwanda. This can also be interpreted as the UK outsourcing its international and humanitarian obligations to a third country, effectively relocating and shifting refugee protection and asylum assessment responsibilities away from its territory. The UK's financial investment in the plan suggests a transactional approach to asylum, paying Rwanda to manage individuals otherwise responsible for the UK.

Moreover, this strategy allows the UK to potentially circumvent some of the more challenging aspects of asylum governance, such as legal complexities, public and political scrutiny, and the resource demands of hosting asylum seekers. However, critics argue that this may compromise the rights and welfare of the asylum seekers and have questioned Rwanda's ability to adhere to the same standards of protection and due process that should be expected within the UK.[xl] To support the efficacy of the Rwanda Plan, the UK is also taking several other measures to curb irregular migration and funding social media campaigns in key countries of origin, such as Albania and Vietnam, to deter irregular migration through small boats.[xli] The more considerable success of these interventions in deterring irregular migration remains unclear and requires further research.

b. Migrants’ Rights and Agency:

While the UK government may have taken an assertive stand on deterring irregular migration, several UK-based NGOs, charities and mutual aid groups have continued to support migrants in need and advocate on their behalf.[xlii] Migrant Rights agencies in the UK and key destination countries have also held several public protests highlighting that the Rwanda Plan compromises migrants' right to free movement and the right to asylum. They claim that the Rwanda Plan has been made without considering the perspectives and lived reality of migrants.[xliii]

For instance, the "Stop the Hate" protest in front of the UK Home Office, which took on Migrants Day on 18th December 2023, denounced the Rwanda Plan and highlighted that in place of such regressive policies, developed countries should adopt initiatives and regulations that highlight the positive contribution of migration and refugees Governments may work together to find regular migration pathways and foster a human rights-based approach. [xliv]

Much of the media narrative and research has focused on the impact of the Rwanda Plan on Britain’s migration policy. But the larger question remains under-discussed: what repercussions does the Plan have for Rwanda and the refugees it already hosts there? Rwanda is one of Africa's most densely populated countries and is known for hosting refugees in the region. It currently hosts more than 135,000 refugees and asylum seekers.[xlv] Most are from the Democratic Republic of Congo and Burundi. Rwanda also faces development challenges, including a high poverty rate, which is essential for its ability to host refugees. Hosting another hundred thousand migrants from the UK may cause additional administrative and resource burdens. Thus, migrant rights and human rights groups maintain that the Rwanda Plan compromises the peace and stability for migrants and asylum-seekers in the region there.

c. Future of Migration Policy:

The more significant questions that the Rwanda Plan raises remain unanswered – will it solve the problem of ‘irregular migration’ or set a dangerous precedent for the rest of Europe?

As the UK gears up for its first flight to Rwanda, major reactions from key destination countries are anticipated and would be crucial to interpret. Just days after the UK government passed its Rwanda deportation bill and gave its initial response to the Rwanda Plan this week, French President Macron criticised the Plan as a [European] ‘betrayal of values’. Given Europe's complicated history with African nations, the Rwanda Plan could spark extensive debates about externalisation, resource sharing, and burden sharing. In another statement from the Council of Europe's (CoE) Commissioner for Human Rights, Michael O'Flaherty said, "The United Kingdom government should refrain from removing people under the Rwanda policy and reverse the bill's effective infringement of judicial independence."[xlvi]

However, the Rwanda Plan is not the first experiment with border externalisation. In 2001, Australia developed a similar ‘offshore’ solution. Under its Pacific Solution policy, the Australian government began sending small boat migrants to Nauru and Papua New Guinea. In 2021, Australia ended its agreement with Papua New Guinea, leaving Nauru as its sole offshore host.

Europe has historically been the epicentre of migratory flows. Thereby, the UK-Rwanda Plan has more significant ramifications. It highlights not only the fissures in Britain’s migration politics but also raises concerns about the future of immigration policy. With increasing global anti-migrant sentiments and irregular migration flows, several governments are considering similar measures, showing a subtle endorsement of the Rwanda Plan. Neighbouring countries, including Denmark and Italy, experimented with the idea of having a similar offshore asylum processing framework. For instance, in 2023, Italy announced a scheme to build two centres in Albania to host up to 36,000 irregular migrants annually. However, Albania’s constitutional court temporarily blocked the scheme. Austria and Germany are also considering having similar frameworks for offshore processing.[xlvii]

Jessica Hagen Zanker, a migration expert at the Overseas Development Institute, points to the EU’s recent Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Tunisia as the latest example of such "cash for migration control" policies. The MoU includes migration and mobility as pillars. It commits €150 million to various sectors, including enhancing Tunisia's migration control capabilities.[xlviii]

CONCLUSION

In summary, the UK-Rwanda Plan represents a pivotal moment in the discourse on global migration and asylum policy. Now that the Safety of Rwanda Bill has been passed by the UK Parliament, concrete implications on how the Plan will affect migration governance and asylum policies require further research and study. This Special Report has detailed the journey of the Rwanda Plan and, through it, exemplified the changing discourse of immigration debates in the UK. The Special Report also highlights the debate on the ethical and practical dimensions of externalising asylum responsibilities, especially when done by a developed country. Despite the controversy and legal setbacks, the commitment of the Conservative Party to ‘stop the boats’ has seen the light of the day now.

Critics argue that the Plan compromises the welfare of migrants by outsourcing the UK's asylum obligations to Rwanda, a nation already grappling with its socio-economic challenges and substantial refugee populations. The debate extends beyond the UK's borders, highlighting broader implications for global migration governance. Instances of public protest and advocacy emphasise the need for policies that respect migrants' rights and recognise their contributions rather than merely implementing restrictive measures.

Furthermore, the UK's approach has influenced other nations, prompting a reevaluation of migration policies across Europe and beyond. The growing trend toward externalising border control reflects a shift in how nations attempt to address migration, often at the expense of human rights and international cooperation.

As countries increasingly mull over adopting similar strategies, the future of migration policy hangs in the balance, necessitating a critical examination of the principles guiding international asylum and migration governance. The UK-Rwanda Plan, therefore, does not just reshape British migration policy; it also sets a precedent that could redefine the global approach to managing migration, with profound implications for the rights and dignity of migrants worldwide.

*****

*Ambi is a Research Associate at the Centre for Migration, Mobility and Diaspora Studies (CMMDS) under the Indian Council of World Affairs (ICWA) in New Delhi.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal.

Endnotes

[i] UK Parliament Committees. 2024. “Asylum Accommodation & Rwanda: Public Accounts Committee Launches Inquiry - Committees - UK Parliament.” 2024. https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/127/public-accounts-committee/news/200242/asylum-accommodation-rwanda-public-accounts-committee-launches-inquiry/.

[ii] UK Home Office. n.d. “Irregular Migration to the UK, Year Ending December 2023.” GOV.UK. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/irregular-migration-to-the-uk-year-ending-december-2023/irregular-migration-to-the-uk-year-ending-december-2023.

[iii] Limited, Alamy. n.d. “Vector Map of the English Channel between United Kingdom and France Stock Vector Image & Art - Alamy.” Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.alamy.com/vector-map-of-the-english-channel-between-united-kingdom-and-france-image459037384.html.

[iv] Walsh, Peter William, and Mihnea. V Cuibus. n.d. “People Crossing the English Channel in Small Boats.” Migration Observatory. Accessed April 25, 2024. https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/people-crossing-the-english-channel-in-small-boats/.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid. (ii)

[vii] The Time. 2024. “2 Men Charged After Deaths of 5 Migrants in English Channel | TIME.” April 2024. https://time.com/6969960/five-migrants-dead-uk-channel/.

[viii] Walsh, Peter William, and Mihnea. V Cuibus. n.d. “People Crossing the English Channel in Small Boats.” Migration Observatory. Accessed April 25, 2024. https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/people-crossing-the-english-channel-in-small-boats/.

[ix]Refugee Council UK, n.d. “The Truth about Asylum.” Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/information/refugee-asylum-facts/the-truth-about-asylum/.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Noack, and Karla Adam. 2021. “After More than Two Dozen Migrants Drown in the English Channel, France and Britain Spar over Solutions to the Problem - The Washington Post.” 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/france-migrants-english-channel-drowning/2021/11/25/e4d984f2-4d7f-11ec-a7b8-9ed28bf23929_story.html.

[xii] Gower, Melanie. 2024. “Irregular Migration: A Timeline of UK-French Co-Operation,” January. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9681/.

[xiii] UK Government. 2023. “Prime Minister Outlines His Five Key Priorities for 2023.” GOV.UK. January 5, 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/prime-minister-outlines-his-five-key-priorities-for-2023.

[xiv] Davidoff-Gore, Hanne Beirens, Samuel. 2022. “The UK-Rwanda Agreement Represents Another Blow to Territorial Asylum.” Migrationpolicy.Org. April 21, 2022. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/uk-rwanda-asylum-agreement.

[xv] Walsh, Peter William. 2024. “Q&A: The UK’s Policy to Send Asylum Seekers to Rwanda.” Migration Observatory. 2024. https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/commentaries/qa-the-uks-policy-to-send-asylum-seekers-to-rwanda/.

[xvi] UNHCR. n.d. “UK-Rwanda Asylum Partnership.” UNHCR UK. Accessed April 2, 2024. https://www.unhcr.org/uk/what-we-do/uk-asylum-policy-and-illegal-migration-act/uk-rwanda-asylum-partnership.

[xvii] UK Parliament. 2022. “PM Speech on Action to Tackle Illegal Migration: 14 April 2022.” GOV.UK. April 14, 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-speech-on-action-to-tackle-illegal-migration-14-april-2022.

[xviii] UK Home Office. n.d. “Migration and Economic Development Partnership with Rwanda: Equality Impact Assessment.” GOV.UK. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/migration-and-economic-development-partnership-with-rwanda/migration-and-economic-development-partnership-with-rwanda-equality-impact-assessment-accessible.

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] Ibid. (xviii)

[xxii] Donnell, Emillie. 2023. “UK Supreme Court Finds UK-Rwanda Asylum Scheme Unlawful | Human Rights Watch.” November 15, 2023. https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/11/15/uk-supreme-court-finds-uk-rwanda-asylum-scheme-unlawful.

[xxiii] Bullen, Poppy, and Naomi Bartram. 2024. “Rwanda Plan Explained: Why the UK Government Should Rethink the Scheme | International Rescue Committee (IRC).” January 16, 2024. https://www.rescue.org/uk/article/rwanda-plan-explained-why-uk-government-should-rethink-scheme.

[xxiv] Refugee Council. 2024. “The Truth about Asylum.” Refugee Council. 2024. https://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/information/refugee-asylum-facts/the-truth-about-asylum/.

[xxv] Umuhoza, Victoire Ingabire. 2023. “The New ‘Rwanda Deal’ Was a Shock to Rwandans. We Know This Is No Place for Asylum Seekers.” The Guardian, December 12, 2023, sec. Opinion. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/dec/12/rwanda-deal-rwandans-asylum-seekers-human-rights.

[xxvi] Ibid. (ii)

[xxvii] Al Jazeera. 2023. “UK to Introduce Law to Override ECHR after Blocked Deportations.” Al Jazeera. 2023. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/6/22/uk-to-introduce-law-to-override-echr-after-blocked-deportations.

[xxviii] Ibid. (ii)

[xxix] Ibid (vii)

[xxx] UK Parliament. 2023. “Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Bill - Hansard - UK Parliament.” December 15, 2023. https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2023-12-12/debates/FA4DDF9F-19EF-4954-9BFA-6997E4A74E79/SafetyOfRwanda(AsylumAndImmigration)Bill.

[xxxi] Castle, Stephen, and Abdi Latif Dahir. 2023. “Sunak’s New Rwanda Bill Aims to Override Some Human Rights Law.” The New York Times, December 6, 2023, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/06/world/europe/uk-bill-asylum-rwanda.html.

[xxxii] Compiled by the Researcher.

[xxxiii] Gower, Butchard, & McKinney. (2023, December 6). The UK-Rwanda Migration and Economic Development Partnership. House of Common Library. Retrieved April 14, 2024, from https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9568/

[xxxiv] Ibid.

[xxxv] Braverman, Suella. 2023. ‘Illegal Migration Bill - Hansard - UK Parliament’. 2023. https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2023-03-07/debates/87B621A3-050D-4B27-A655-2EDD4AAE6481/IllegalMigrationBill.

[xxxvi] Ibid. (xi)

[xxxvii] Ibid.

[xxxviii] Ibid.

[xxxix] Ibid. (ii)

[xl] Sen, Piyal, Grace Crowley, Paul Arnell, Cornelius Katona, Mishka Pillay, Lauren Z. Waterman and Andrew Forrester. “The UK's exportation of asylum obligations to Rwanda: A challenge to mental health, ethics and the law.” Medicine, Science and the Law 62 (2022): 165 - 167.

[xli] UK Home Office. n.d. “International Social Media Campaign Launched to Stop the Boats.” GOV.UK. Accessed April 2, 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/international-social-media-campaign-launched-to-stop-the-boats.

[xlii] McDonald, Anton. n.d. “The UK’s ‘Rwanda’ Immigration Bill, Explained.” FairPlanet. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.fairplanet.org/story/the-uks-rwanda-immigration-bill-explained/.

[xliii] Srivastava, Sanjay. 2024. “UK’s Rwanda Bill: Why It’s a Solution That Doesn’t Work.” The Indian Express (blog). April 25, 2024. https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/uks-rwanda-bill-why-its-a-solution-that-doesnt-work-9289157/.

[xliv] AfricaNews. 2023. “Protesters Rally against Government’s Migration Policies Outside UK Home Office.” Africanews. December 19, 2023. https://www.africanews.com/2023/12/19/protesters-rally-against-governments-migration-policies-outside-uk-home-office/.

[xlv] Easton-Calabria, Evan. 2023. “UK’s Failed Asylum Deportation Plan Puts Rwanda’s Human Rights and Refugee Struggles in the Spotlight.” The Conversation. November 24, 2023. http://theconversation.com/uks-failed-asylum-deportation-plan-puts-rwandas-human-rights-and-refugee-struggles-in-the-spotlight-218263.

[xlvi] France 24. 2024. “Council of Europe Calls on UK to Scrap Rwanda Migrant Plan.” France 24. April 23, 2024. https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20240423-council-of-europe-calls-on-uk-to-scrap-rwanda-migrant-plan.

[xlvii] Ibid.

[xlviii] Hagen-Zanker, Jessica. 2024. “Why Many Policies to Lower Migration Actually Increase It.” The Conversation. April 19, 2024. http://theconversation.com/why-many-policies-to-lower-migration-actually-increase-it-227271.