Indian Council of World Affairs

Sapru House, New DelhiCambodia: China’s Gateway to the Gulf of Thailand?

The waters of eastern Asia have been a zone of contestation, owing largely to the persistent issue of unresolved maritime territorial claims and counter-claims in the Sea of Japan, Yellow Sea, and East and South China Seas. There have been escalations due to the periodic missile testing by North Korea and exchanges over Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands dispute between Beijing and Tokyo, but then the Far East has not seen the same level of heightened tensions as in the South China Sea. For more than a decade now, the South China Sea has been in a state of near-permanent hostilities between China and the other claimants to the disputed territorial waters like the Philippines and Vietnam, along with the periodic escalation of hostilities with Taiwan, a legacy issue that can go back to the days of the Communist Revolution in the Middle Kingdom.

Map I: Gulf of Thailand

Source: Gulf Of Thailand, World Atlas, https://www.worldatlas.com/gulfs/gulf-of-thailand.html.

It is against this backdrop that the nature of developments in the Gulf of Thailand gains significance, as this water body until recently was seen to be free of geo-political contestation. While the situation has not escalated to become another flash point, there have been developments around the coastal city of Sihanoukville, also known as Kampong Saom, and the capital of the coastal province of Preah Sihanouk in Cambodia that have the potential to change the geopolitical landscape and, concurrently, the security dynamics of this part of the world.

The first development of concern is the presence of People’s Liberation Army-Navy (PLA-N) vessels being spotted in the Ream Naval Base of the Kingdom of Cambodia. What makes the docking of the two PLA-N corvettes in Ream, which is located just north of Sihanoukville, a cause for concern is that their presence is not part of a regular port call. To the contrary, the PLA-N vessels have been anchored almost continuously in this Cambodian base for many months now, beginning mid-December 2023.[i] Additionally, based on geospatial satellite imagery data, the PLA-N assets have been docked almost exclusively at the new pier at Ream, which has been constructed by China.

The second development, which is still in its initial stage, is the Funan Techo Canal, formerly known as the Tonle Bassac Navigation Road and Logistics System Project. This proposed project would connect the riverine autonomous port of the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh with the Gulf of Thailand. This proposed 180-km-long canal is to be constructed for an estimated $1.7 billion. Even at this early stage, this proposed canal has become a cause for concern for Vietnam, as Hanoi fears a significant diversion of water from the Mekong River system.

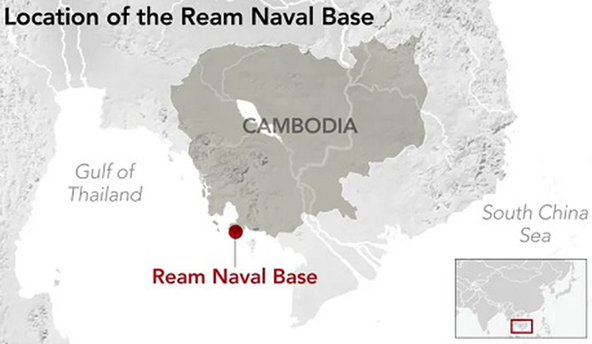

Ream Naval Base

For a country with a coastline of 443 km/275 miles, Cambodia's maritime footprint has been timid. Reasons for this can be attributed to a narrow and weak economic base, a turbulent political history that has seen the extremities of the likes of the Khmer Rouge and the resultant unravelling of the social-political-economic structures of the nation, and also limited external engagement as an instrument of foreign policy. Resultantly, the country has had a history of limited international trade that has resulted in Cambodia neglecting its maritime capabilities and capacity.

It has only been in the recent past that Ream Port has been given a new lease of life. In January 2019, the US Senate Intelligence Committee was apprised of the prospects of a ‘Chinese military presence’ in Cambodia.[ii] Resultantly, since then, China has been involved in developing this maritime facility. In July 2023, a spokesman for the Cambodia National Defence Ministry confirmed that the renovation works were near completion. The Ministry added that the allegations of the Chinese military using this base in the future were ‘untrue information’.[iii]

Map II: Location of Ream Naval Base

Source: Ream Naval Base, Vajiram and Ravi, https://vajiramias.com/current-affairs/ream-naval-base/5d3aa1c11d5def7122290865/

The nature of such involvement has only gone on to give credence to the past suspicion from some quarters that Beijing has been working on a secret naval base in Cambodia, thereby extending its military footprint. The prospects of a Chinese base in the Gulf of Thailand would have significant implications both in terms of the larger regional security architecture and more so concerning the disputed waters of the South China Sea. Ream, with its 363-metre-long piers, similar to those of China’s first overseas base in Djibouti, can accommodate the berthing of larger vessels like aircraft carriers.[iv] Additionally, the Ream facility covers a total of 187 hectares, including 30 hectares for a naval radar system.[v] Apart from this, open-source intelligence has identified extensive fuel storage capacity,[vi] indicating that this facility is not to service the limited requirements of Cambodia’s small patrol boats but larger vessels or a larger fleet of vessels of the like that PLA-N has or even its shadow maritime militia fleet of fishing vessels.

This kind of development, in other words, can only be interpreted as China having another military facility in the vicinity of the disputed waters of the South China Sea, going beyond its extensive facilities in both the illegally reclaimed territories of the disputed waters as well as on the Chinese mainland. However, what is most important is that the Chinese have systematically been moving their immediate frontiers away from the mainland by sticking to their age-old salami-slicing tactics. Even though the Ream facility may not contribute significantly to the PLA-N’s operational capabilities, it will add a layer of complication for rival military planners.

Funan Techo Canal

Vietnam has already expressed concerns over the proposed canal, primarily on ecological and environmental grounds, as Hanoi’s fisheries and agricultural sectors could be adversely impacted. Vietnam estimates that a third of the water that flows into the upstream Hậu River or Bassac River would be diverted because of this canal, thereby exasperating the already existing concerns about downstream salinity in the Mekong Delta.[vii]

However, Cambodia, on its part, has dismissed these concerns and said that the ecological impact would be to the bare minimum, as only 0.053 per cent of the water that flows in the Mekong River would be utilised by this canal.[viii] It is expected that ground will be broken for the Funan Techo Canal, which will link the Phnom Penh Autonomous Port in the inland capital city with the planned deepwater port in Kep province via the Bassac River, a tributary of the Mekong. The canal will act as a waterway that will connect the capital city with the Cambodian coast in Kep, and from there further, link up with the Cambodian seaports like Sihanoukville and Kampot.[ix] With respect to the latter in May 2023, China Harbour Engineering Co Ltd (CHEC) commenced work on developing Kampot Logistics and Port Co Ltd with an investment of $1.5 billion.[x] The groundbreaking for the construction of the 180- km-long is expected by the end of 2024,[xi] or maybe as early as August 2024.[xii] and is expected to become operational by 2028.[xiii] The canal will be constructed with a consistent depth of 5.4 metres and a width of 80-00 metres.[xiv] With this draft, this inland waterway will accommodate larger vessels of 3,000 deadweight tonnage (DWT).

Map III: Funan Techo Canal

Source: Funan Techo Canal (Bassac Sea-Link): A waterway and canal system connecting Phnom Penh to Kampot, Future of Southeast Asia, https://futuresoutheastasia.com/bassac-sea-link/.

It is estimated that the Funan Techo Canal could improve the livelihoods of more than 1.6 million people living along the route, as economic activities like agriculture, irrigation, aquaculture, and livestock would be supported by the canal.[xv] It is estimated that the canal can supply water for over 300,000 hectares in the Kandal and Kampot provinces of Cambodia.[xvi]

This inland water system is expected to reduce Phnom Penh’s dependency upon neighbouring Vietnamese ports in Cai Mep, which is 50 km southeast of Vietnam's commercial hub, Ho Chi Minh City by 70 per cent for its international trade[xvii] and can potentially reduce shipping costs by a third.[xviii] It was in this context that Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Manet made the loaded statement that the nation can breathe ‘through our own nose’,[xix] alluding to economic and shipping blockades by Vietnam. Prime Minister Hun Manet was referring specifically to the 1994 shipping blockade by Hanoi, which was allegedly triggered by the ‘Vietnamese displeasure over the new Cambodian immigration law, which it considers discriminatory against the ethnic Vietnamese in Cambodia’.[xx]

Going beyond the burden of history, this canal is being projected as a part of Phnom Penh’s Pentagonal Strategy, a 25-year plan to make Cambodia a high-income country.[xxi] To realise this ambition, it is imperative for Cambodia to accelerate its economic progress. This would translate into greater integration of the country with the global supply chain without being dependent upon third-party intermediaries for trade and transit. In this context, this inland waterway, once operational, is expected to generate employment for 5 million people.[xxii]

On the flip side, criticism about the Funan Techo Canal primarily stems from the fact that it is to be executed under the aegis of the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Like most BRI initiatives, details of the cost and commercial viability are uncertain. Ecological and environmental impact assessments are unclear, at best. And there is little information on the human impact in terms of displacement and loss of existing livelihood.

Map IV: Funan Techo Canal

Source: Cambodia, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cambodia.

It should be noted that 41 per cent of the kingdom’s total external debt of $10 billion is already owed to China.[xxiii] In this context, uncertainties over the commercial and financial aspects of the canal will further deepen Beijing’s foothold over Phnom Penh. This, in turn, has larger geopolitical and geostrategic implications, which will not be limited to the Indo-China region but also the larger Indo-Pacific region.

Redrawing of Geography

In the immediate future, this canal is seen as challenging the spirit of the 1995 Mekong Agreement between Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam for the judicious management of the Mekong River basin. Vietnam has expressed its concerns that the Funan Techo would violate the 1995 Agreement; however, Cambodia has dismissed the same. From the perspective of Phnom Penh, this project would be utilising that portion of the Mekong basin, which lies completely within Cambodia. The water that would be used would only be a small fraction and would not be a source of concern for the lower riparian Vietnam. It is on this basis that Phnom Penh has taken the position that this project would not be violating the 1995 Mekong Agreement.

However, concerns about the lowest riparian, Vietnam are further accentuated for other reasons. The proliferation of hydro projects along the Mekong, beginning with China, the river's source, has already had a negative impact on the flow of water along the Mekong River basin. China has played a significant role in developing hydro projects in both Cambodia and Laos. These undertakings, by and large, have been to the detriment of the host countries but have been to the benefit of China, especially the hydroelectricity that is being generated. Thus, the disruption of the river’s flow along with its nutrient-rich sediment has negatively impacted the communities that have been deepened on Mekong’s waters their livelihood for centuries now.

According to Cambodian Deputy Prime Minister Sun Chanthol, Funan Techo would be under Chinese management before being transferred to Phnom Penh. He hinted that the gestation period, which is yet to be finalised, could be between 30 and 50 years[xxiv]. This would impact the regional geological and security dynamics. While taking into account the PLA-N presence in Ream, which is in proximity to the Kep, the entrepot for this inland waterway, and the overall dependency of Cambodia on China, the multi-decade gestation period has the potential to change the geo-political landscape of the region and become yet another area of concern for Vietnam, especially in light of the uncomfortable relationship between Hanoi and Beijing.

With a draft that can accommodate mid-size vessels of 3000 DWT, apprehension has already been expressed about the potential dual use and militarisation of this inland waterway.

Map V: Chinese Presence in Coastal Cambodian

Source: Cambodian PM Retaliates Against US Arms Embargo, Orders Military to Destroy US Arms, Statecraft, https://www.statecraft.co.in/article/cambodian-pm-retaliates-against-us-arms-embargo-orders-military-to-destroy-us-arms#google_vignette.

Though the source and nature of potential investment in Cambodia are still too early to identify, it can be speculated that China could take an active economic interest in Cambodia in the future. This in turn would translate into Beijing’s economic footprint deepening in the Indo-China region beyond the existing trade and debt-driven infrastructure diplomacy.

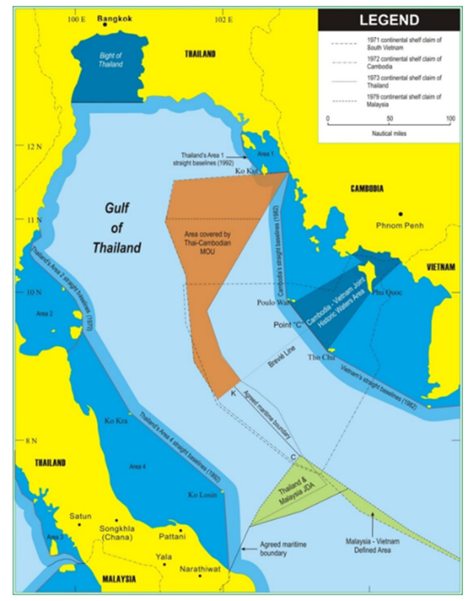

Map VI: Thailand Cambodia Overlapping Claims Area

Source: Thailand Cambodia Overlapping Claims Area. Is a settlement in sight? CLC Asia, https://www.clc-asia.com/thailand-cambodia-overlapping-claims-area/.

The long arm of Chinese outreach

However, both the Ream Naval Base and the Funan Techo Canal are not only a concern for Hanoi but can also have implications for the other littorals of the Gulf of Thailand, where Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam have overlapping maritime territorial claims. While maritime claims have not yet become a contagious issue, the resource reserves of 11 trillion cubic feet of natural gas and 500 million barrels of oil,[xxv] along with fisheries, could make the Gulf of Thailand a flash point in the future.

For China, any interstate tensions or apprehensions of the same in the Gulf of Thailand would enable Beijing to play the role of an outside balancer. Secondly, another unresolved issue in this theatre would dilute the internal cohesion of ASEAN, which is already strained. The third and finally, the Gulf of Thailand would add another layer to the checkered tapestry in the Indo-Pacific region. Thus, comprehending the security architecture of the Indo-Pacific region would also be further complicated.

*****

*Dr. Sripathi Narayanan, Research Fellow, Indian Council of World Affairs, New Delhi.

The views expressed are personal.

[i] “First Among Piers: Chinese Ships Settle in at Cambodia’s Ream”, Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, April 18, 2024, https://amti.csis.org/first-among-piers-chinese-ships-settle-in-at-cambodias-ream/, accessed on April 26, 2024.

[ii] Daniel R Coats, “Statement for the Record Worldwide Threat Assessment of the US Intelligence Community”, United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, January 29, 2019, Page 29, https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/2019-ATA-SFR---SSCI.pdf, accessed on May 14, 2024.

[iii] Sun Narin and Han Noy, “Cambodian Ream Naval Base Modernized by China Nears Completion: Defense Ministry”, Voice of America, July 26, 2023,

https://www.voanews.com/a/cambodian-ream-naval-base-modernized-by-china-nears-completion-defense-ministry/7198994.html, accessed on May 8, 2024.

[iv] Rep. Rob Wittman and Craig Singleton, “With Chinese warships anchoring in Cambodia, the US needs to respond”, Defense News, May 3, 2024, https://www.defensenews.com/opinion/2024/05/03/with-chinese-warships-anchoring-in-cambodia-the-us-needs-to-respond/, accessed on May 8, 2024.

[v] Gabriel Honrada, “China suspected of building aircraft carrier base in Cambodia”, Asia Times, July 27, 2023,

https://asiatimes.com/2023/07/china-suspected-of-building-aircraft-carrier-base-in-cambodia/, accessed on May 20, 2024.

[vi] Sakshi Tiwari, “China’s Naval Base In Cambodia Undergoes Rapid Construction; Can Host An Aircraft Carrier – Satellite Images Reveal: Eurasian Times, February 23, 2024, https://www.eurasiantimes.com/chinas-naval-base-in-cambodia-undergoes-rapid/, accessed on May 20, 2024.

[vii] “Cambodian Funan Techo Canal might reduce water flow to Hậu River: Experts”, Vietnam Times, April 24, 2024, https://vietnamnews.vn/society/1654422/cambodian-funan-techo-canal-might-reduce-water-flow-to-hau-river-experts.html?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email, accessed on April 25, 2024.

[viii] “Even critic denies military value of Funan Techo Canal”, Phnom Penh Post, May 13, 2024, https://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/even-critic-denies-military-value-of-funan-techo-canal, accessed on May 29, 2024.

[ix] Cambodia starts construction of $1.5bn Kampot port, Seatrade Maritime News, May 9, 2024, https://www.seatrade-maritime.com/ports-logistics/cambodia-starts-construction-15bn-kampot-port, accessed on May 10, 2024.

[x] Construction contract inked for $1.5B Kampot port, Phnom Penh Post, May 6, 2023, https://www.phnompenhpost.com/business/construction-contract-inked-15b-kampot-port, accessed on May 3, 2024.

[xi] “Transport Minister: Funan Techo Canal Project to Begin Construction in Late 2024”, Khmer Times, January 18, 2024, https://www.khmertimeskh.com/501425184/transport-minister-funan-techo-canal-project-to-begin-construction-in-late-2024/, accessed on May 28, 2024.

[xii] PM: Funan Techo Canal construction to begin August, Phnom Penh Times, May 30, 2024, https://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/pm-funan-techo-canal-construction-to-begin-august, accessed on May 30, 2024.

[xiii] “Even critic denies military value of Funan Techo Canal,” Phnom Penh Times, May 29, 2024,

https://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/even-critic-denies-military-value-of-funan-techo-canal, access on May 30, 2024.

[xiv] Lors Liblib, “Cambodia Tries to Reassure Vietnam That Proposed Canal Won't Affect Mekong River”, Voice of America, December 21, 2023, https://www.voanews.com/a/cambodia-tries-to-reassure-vietnam-that-proposed-canal-won-t-affect-mekong-river/7406682.html, accessed on March 28, 2024.

[xv] “Transport Minister: Funan Techo Canal Project to Begin Construction in Late 2024”, Khmer Times, January 18, 2024, https://www.khmertimeskh.com/501425184/transport-minister-funan-techo-canal-project-to-begin-construction-in-late-2024/, accessed on May 28, 2024.

[xvi] “Cambodian Funan Techo Canal might reduce water flow to Hậu River: Experts”, Vietnam Times, April 24, 2024, https://vietnamnews.vn/society/1654422/cambodian-funan-techo-canal-might-reduce-water-flow-to-hau-river-experts.html?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email, accessed on April 25, 2024.

[xvii] Chantha Lach and Francesco Guarascio, “Cambodia says it will cut shipping through Vietnam by 70% with new China-funded Mekong canal”, Reuters , May 7, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/cambodia-says-it-will-cut-shipping-through-vietnam-by-70-with-new-china-funded-2024-05-07/, accessed on May 9, 2024.

[xviii] David Hutt, “The Funan Techo Canal Won’t Have A Military Purpose, The Diplomat, May 23, 2024,

https://thediplomat.com/2024/05/the-funan-techo-canal-wont-have-a-military-purpose/#:~:text=Phnom%20Penh%20reckons%20it%20could,Cambodia's%20dependence%20on%20Vietnam's%20ports, accessed on May 23, 2024.

[xix] Richard S Ehrlich, “Cambodia getting a China-backed, game-changing canal”, Asia Times, April 1, 2024,

https://asiatimes.com/2024/04/cambodia-getting-a-china-backed-game-changing-canal/, accessed on April 1, 2024.

[xx] “Chronology for Vietnamese in Cambodia”, UNHRC, 2004, https://webarchive.archive.unhcr.org/20230520032123/https://www.refworld.org/docid/469f38741e.html, accessed on May 29, 2024.

[xxi] Pentagonal Strategy - Phase I for Growth, Employment, Equity, Efficiency, and Sustainability: Building the Foundation towards Realizing the Cambodia Vision 2050., UN FAO, December 5, 2023, https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC222534/#:~:text=The%20Pentagonal%20Strategy%20is%20the,approach%20related%20to%20good%20governance, accessed on May 29, 2024.

[xxii] Vietnam and Cambodia Clash Over New Mekong Canal, Maritime Executive, June 2, 2024, https://maritime-executive.com/editorials/vietnam-and-cambodia-clash-over-new-mekong-canal, accessed on June 3, 2024.

[xxiii] Lors Liblib, “Cambodia Tries to Reassure Vietnam That Proposed Canal Won't Affect Mekong River”, Voice of America, December 21, 2023, https://www.voanews.com/a/cambodia-tries-to-reassure-vietnam-that-proposed-canal-won-t-affect-mekong-river/7406682.html, accessed on March 28, 2024.

[xxiv] Chantha Lach and Francesco Guarascio, “Cambodia says it will cut shipping through Vietnam by 70% with new China-funded Mekong canal”, Reuters , May 7, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/cambodia-says-it-will-cut-shipping-through-vietnam-by-70-with-new-china-funded-2024-05-07/, accessed on May 9, 2024.

[xxv] “How has Koh Kood become a Thai-Cambodia Political Issue?”, Khaosod Rnglish, March 9, 2024 https://www.khaosodenglish.com/news/2024/03/09/how-has-koh-kood-become-a-thai-cambodia-political-issue/, accessed on May 1, 2024.