Indian Council of World Affairs

Sapru House, New DelhiNavigating the Humanitarian Dilemma in Afghanistan

Abstract: Afghanistan is currently confronted with one of the world's most enduring, severe and complex humanitarian crises. Although there is an acknowledgement that aid is essential for the country’s survival, the global community is grappling with the dilemma of finding ways to support the Afghan people without inadvertently bolstering the Taliban through their assistance.

Introduction

More than three years after the chaotic US withdrawal, Afghanistan has largely disappeared from the headlines, yet its challenges remain pressing. The country is experiencing one of the most enduring, severe and complex humanitarian crises globally. Since the Taliban assumed power in August 2021, economic and political instability has severely disrupted access to services across Afghanistan, resulting in many households having difficulty meeting their basic needs. The combined effects of economic collapse, displacement and climate-related disasters — such as droughts, earthquakes and floods — have left “approximately 23.7 million people, over half the population, in need of humanitarian assistance in 2024,” according to the UN.[i] Although the international community, aid organisations and the Taliban agree that aid is crucial for the country’s survival, disagreements over how to establish a unified and coordinated system of delivery, coupled with the Taliban’s refusal to compromise on specific policy issues, further complicate the situation. The global community faces the challenge of supporting the Afghan people without inadvertently empowering the Taliban through their aid efforts. Against this backdrop, this ICWA Issue Brief seeks to shed light on the complexities of Afghanistan's humanitarian dilemma.

Triggers of the Humanitarian Crisis in Afghanistan

Afghanistan is amongst “the poorest and least developed countries globally, ranked 182 out of 193 nations and territories” on the Human Development Index.[ii] Upon taking power on August 15, 2021, the Taliban inherited substantial macroeconomic challenges. Before the fall of the Afghan Republic, foreign aid made up 40% of the country’s GDP, supported more than half of the Afghan government’s $6 billion annual budget, and financed 75% to 80% of public spending.[iii] The abrupt change of regime, along with the rapid removal of global assistance, plunged the nation into an economic collapse and triggered a severe humanitarian crisis. The effects on Afghanistan’s economy were exacerbated by sudden diplomatic and financial isolation.

In accordance with longstanding sanctions imposed by the US and the UN on Taliban leaders, many of whom were assigned to key positions in the interim cabinet following the takeover, the US froze nearly $9.5 billion of Afghanistan’s external reserves. This left Da Afghanistan Bank (DAB), the central bank of Afghanistan, without access to its assets and isolated from the global financial system. The result was a severe liquidity crisis, a halt to normal financial transactions with foreign banks, and the paralysis of Afghanistan’s commercial banking sector. To safeguard some of the frozen funds from being claimed by the families of 11 September victims — who had won a $7 billion default judgement against the Taliban in 2011 — the Biden administration allocated $3.5 billion of the assets to create the Swiss-based Fund for the Afghan People.[iv] This fund was designed to provide focused distributions to maintain Afghanistan’s macroeconomic and financial stability. However, as of September this year, the fund is yet to be utilized.

To aggravate matters further, four 6.3-magnitude earthquakes struck northwestern Afghanistan’s Herat Province in October 2023, resulting in widespread humanitarian need in the province.[v] In addition, severe flooding in northern, northeastern and western Afghanistan in May-June 2024 resulted in hundreds of deaths and significant damage to agricultural land and critical infrastructure.[vi] Amid Afghanistan’s struggle to cope with the devastating effects of natural disasters, the Pakistani government announced plans in mid-September 2023 to repatriate an estimated 1.7 million “unregistered” Afghans.[vii] Over 610,000 Afghan refugees have returned back to Afghanistan from Pakistan (as reflected in Table 1 below), with the majority needing food aid, healthcare and opportunities to rebuild their livelihoods in their communities of return.[viii] The arrival of returning Afghans has placed significant strain on already scarce resources, which are further impacted by international sanctions on the banking sector and reductions in foreign aid following the Taliban’s takeover. Afghanistan has appealed for increased international assistance, citing a similar effort by Iran to expel its Afghan population, but many donors remain reluctant to respond.[ix]

Table 1. Afghanistan Humanitarian Situation at a Glance

|

Number of People in Need of Humanitarian Assistance |

Number of People Prioritised for Humanitarian Assistance Under the 2024 Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan (HNRP) |

IDPs in Afghanistan as of December 2022 |

Number of Afghan Returnees from Pakistan Since September 15, 2023 |

|

23.7 MILLION |

17.3 MILLION |

6.6 MILLION |

610,800 |

|

Source: UN – December 2023 |

Source: UN – December 2023 |

Source: IOM – June 2023 |

Source: IOM – June 2024 |

Following a 27% decline in GDP from 2021 to 2023, the country’s economy is now stagnant, heavily dependent on foreign aid, and remains susceptible to various shocks. The World Bank’s Afghanistan Welfare Monitoring Survey[x] indicated that “unemployment remains high, with nearly 20% of households without jobs by mid-2023, and there is no reason to believe that more recent trends will be any better.” The report also mentions that urban areas have been hit hardest by the loss of more than 700,000 jobs, while rural regions are dealing with environmental crises. Furthermore, the Taliban’s 2022 ban on opium poppy cultivation — previously Afghanistan’s most profitable agricultural export — has intensified economic difficulties in rural areas, hindering recovery efforts even further. While some economic indicators have stabilised — such as year-on-year headline inflation decreasing to 3.5%, increased availability of food and non-food items, and a rise in the value of the Afghani against foreign currencies — these improvements have not offered significant relief to the population. The combination of the abovementioned challenges paints a bleak picture of Afghanistan and highlights the need for humanitarian assistance for the country.

Global Community’s Declining Commitment

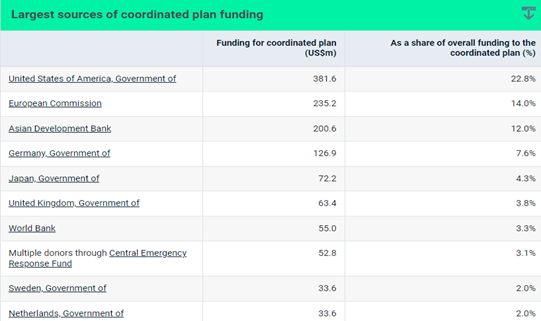

The humanitarian challenges facing Afghanistan are further intensified by a noticeable decline in international support, driven by donor fatigue. Last year, the UN World Food Programme (UNWFP) issued an urgent call for funds to be directed towards Afghanistan, cautioning that an “additional 9 million people could lose access to food aid.”[xi] The WFP identified a “$93 million funding gap for April 2023 and $800 million needed for the following six months,” urging donor countries to respond to the appeal of 2023 Humanitarian Response Plan to prevent the crisis from worsening.[xii] As global attention turns to other crises, Afghanistan's pressing needs are gradually being overshadowed and overlooked. The United Nations Office of Coordination of Humanitarian Assistance (OCHA)’s 2023 Humanitarian Needs Response Plan[xiii] (HNRP) initially called for “a record $4.6 billion in humanitarian aid for Afghanistan, marking its largest-ever funding appeal for a single country.” However, this amount was subsequently revised down to $3.2 billion, not due to improved conditions but because of significant funding shortfalls. The funding gap was substantial, with the Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan falling “$2.96 billion short of its original targets and $1.59 billion below the adjusted budget.”[xiv] This raises concerns for the 2024 HNRP, which aims to secure $3.1 billion. As worries about human rights violations and corruption increase, major donors — such as the US, the UK, the EU and the Asian Development Bank — have become increasingly hesitant to commit aid.

Table 2. Major Contributors of Humanitarian Assistance for Afghanistan

Source: UNOCHA 2024[xv]

The US is the largest donor of humanitarian aid to Afghanistan, providing around $2.1 billion since August 2021.[xvi] However, per USAID, “the US has reduced its financial support, dropping from $1.26 billion in 2022 to $377 million in 2023”[xvii] and “the UK reduced its Afghan aid budget by 76% in 2023, while Germany cut its contributions by 93%.”[xviii] As of 9 May 2024, HNRP 2024 has received only 15.9% of its funding target. Although the Organization of Islamic Countries and the Gulf Cooperation Council had assured to mobilise resources and help Afghanistan, their contributions have been significantly less than those of Western donors. Following the Taliban takeover, Qatar announced $50 million in humanitarian aid to Afghanistan and committed an additional $25 million in 2022.[xix] According to UNOCHA, till 2022, other top Muslim donors in Afghanistan have been Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the UAE, having contributed $11 million, $4 million and $1.9 million, respectively.[xx]

Afghanistan’s regional neighbours have been concerned about the spillover effect of the humanitarian crisis next door; as a result, many of these countries have provided humanitarian support to prevent migration, economic collapse and regional instability.[xxi] Pakistan has announced more than $28 million worth of medical, food and other humanitarian assistance for Afghanistan immediately after the return of the Taliban in Afghanistan.[xxii] The Iranian Red Crescent Society delivered 450 tonnes[xxiii] and 20 tonnes[xxiv] of humanitarian assistance to Afghanistan following earthquakes and floods in 2023 and 2024, respectively. Among the Central Asian countries, Kazakhstan has provided more than $400 million in humanitarian aid and has supplied 70% of the total flour exported to Afghanistan to address food insecurity.[xxv] Uzbekistan has been regularly sending humanitarian aid to Afghanistan; in 2021, Tashkent provided 3,700 tonnes of humanitarian aid.[xxvi] Subsequently, following devastating natural calamities, Uzbekistan sent consignments of humanitarian assistance to Afghanistan. Notably, China — the wealthiest of Afghanistan’s neighbouring countries — has provided only $31 million in humanitarian assistance, despite expressing strong interest in investing in Afghanistan.[xxvii] Iran, Pakistan, Uzbekistan and China have all urged the West to unfreeze Afghanistan’s assets and enhance humanitarian aid.

As part of its ongoing assistance to Afghanistan, India supplied 40,000 litres of Malathion (a pesticide used to combat locust infestations) through the Chabahar Port in January 2024.[xxviii] Earlier, India provided 40,000 metric tonnes (MT)[xxix] of wheat overland via Pakistan in February 2022 and an additional 20,000 MT via Iran’s Chabahar port[xxx] in March 2023, which was distributed through the UN World Food Programme (WFP), along with 45 tonnes of medical assistance in October 2022, including essential life-saving medicines, anti-TB medicines, 500,000 doses of COVID-19 vaccines, winter clothing and tonnes of disaster relief material, among other supplies.[xxxi]

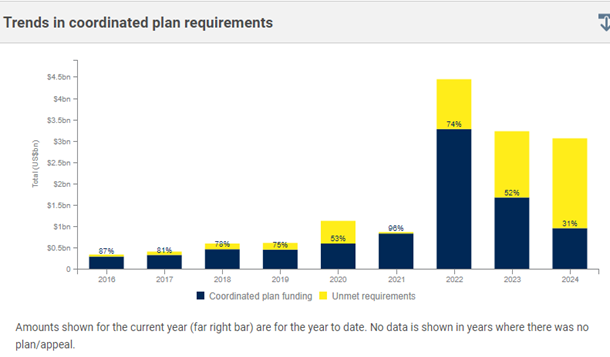

While the humanitarian aid provided to Afghanistan has undeniably been vital, recent UN data shows a steady decline in funding (see Graph 1 below), with only 31.3% of the required amount for 2024 being met.

Graph 1: Funding and Unmet Requirements of Humanitarian Assistance for Afghanistan

Source: Afghanistan Humanitarian Response Plan 2024, UNOCHA

Navigating the Dilemma

It is difficult to pinpoint a single cause for the decline in funding, but the Taliban’s policy decisions, their resource allocation, the international community’s uncertainty about how to engage with the group, and the prioritisation of other global conflicts have played a role in this trend.

Afghanistan presents a stark moral dilemma, where donors must balance two conflicting ethical imperatives: upholding the principle of gender equality and universal human rights versus ensuring the immediate survival and well-being of millions dependent on aid. The Taliban’s policies, including restrictions on women’s employment, contradict fundamental human rights, especially regarding gender equality and women’s rights. Refusing to comply with the policies demonstrates a strong stand against injustice and may send a powerful message, advocating for the dignity and rights of women. However, this approach could result in the withdrawal or reduction of critical aid operations, leaving millions of vulnerable people without access to life-saving assistance. Aid organisations risk indirectly contributing to human suffering by cutting off essential services.

On the other hand, continuing to provide aid, even under restrictive conditions, prioritises the immediate survival of millions who depend on food, shelter and healthcare. In this view, the humanitarian imperative supersedes political or ethical considerations about gender equality in the short term, as millions of lives could be at stake. However, this may legitimise and entrench the Taliban’s oppressive policies, undermining the long-term struggle for gender justice and human rights in the country. The dilemma boils down to a choice between maintaining moral integrity or making pragmatic decisions for the greater good. Each path has consequences; one risks human lives by taking a principled stance, while the other risks compromising long-term human rights progress for short-term survival.

The main challenge is finding a politically viable middle ground between two undesirable choices. However, it is essential to recognize that these options are not mutually exclusive. What is needed is a sequential, step-by-step process involving reciprocal actions from both the Taliban regime and the international community, with a balance of incentives and disincentives.

Apart from moral considerations, Taliban’s policies regarding women’s participation in public spaces have a direct impact on NGOs and their ability to reach those most in need. Women constitute 30% to 40% of the NGO workforce and play a crucial role in ensuring that vulnerable populations receive necessary aid and assistance.[xxxii] When the Taliban prohibited women from working in local and international NGOs, aid programs were severely disrupted, causing approximately 150 organisations to suspend their operations.[xxxiii] Although UN officials obtained exemptions for key sectors, such as education and health, this highlighted how the Taliban’s regressive policies create a ripple effect, disrupting the distribution and provision of aid.[xxxiv]

Another factor that has influenced the donor’s decision is the concern over whether the aid is reaching the intended recipient. Last year, the legal advisor for Afghanistan’s Mission in Geneva accused the Taliban regime of “forcing NGOs to register and provide information, which has led to the interference with the equitable delivery of humanitarian aid.”[xxxv] Reports have emerged of “funds being redirected to Taliban supporters or misused through the hawala system, which has become essential due to the lack of formal banking channels.”[xxxvi] A January 2024 report from the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) revealed that “the Taliban have syphoned off or profited from a significant portion of humanitarian aid,” and tactics reportedly include “infiltrating NGOs partnered with the UN to access aid budgets, imposing taxes and “security” fees on humanitarian workers, instructing aid agencies to prioritise Taliban officials and their families and heavily taxing Afghan aid recipients — sometimes taking as much as 60% to 100% of the aid they receive.”[xxxvii]

Although there is a general acknowledgement that revenue collection has risen under the Taliban, with,” the IEA generating 173.9 billion AFN ($1.95 billion) in the last fiscal year (22 March 2022 to 21 February 2023),” per the World Bank, their spending patterns reveal a concerning trend.[xxxviii] A significant portion of the budget is allocated to security and related sectors, while only 8% is directed toward developmental initiatives. The Taliban are aware that the international community will continue to deliver humanitarian aid and support for essential services, and this is apparent in their budget, where the provision of basic services has not been prioritised, with some left to international agencies to manage.[xxxix] Meanwhile, there has been increased spending on propaganda efforts and for the Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice (MPVPV), all funded through the national budget. A report analysing the Taliban’s 2022/23 budget observed, “The funds allocated to this ministry were equivalent to the entire development budget for the economic and agricultural sectors — covering ministries such as finance, economy, agriculture, commerce and industries, along with the national standards authority, supreme audit office and national statistics and information agency.”[xl] The MPVPV budget was three times the budget allocated to the public health sector. Therefore, the ongoing flow of aid to Kabul may allow the group to continue directing its revenue towards security-related areas while relying solely on external assistance for human development and socio-economic investment.

Conclusion

The international community remains unsure about how to proceed in Afghanistan. While there is recognition that aid is crucial for the country’s survival, the global community is faced with the challenge of finding ways to support the Afghan people without unintentionally strengthening the Taliban through their assistance. To establish a unified approach, last year, the UN Security Council (UNSC) called on the Secretary-General to conduct an assessment and provide "forward-looking recommendations" for creating a cohesive strategy towards Afghanistan. As we move forward, it will be intriguing to observe whether an effective assessment and recommendations can be forwarded to address the challenges faced by Afghanistan. The people of Afghanistan require enduring and maintainable solutions that encompass not just increased humanitarian aid but also enhanced economic stability, the recommencement of development assistance from the international community, and a workable economy driven by the private sector. With the well-being of ordinary Afghans at risk, stakeholders must navigate the available options and strive to find a viable middle ground while remaining steadfast in their commitment to Afghanistan's future.

*****

*Dr. Anwesha Ghosh, Research Fellow, Indian Council of World Affairs.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal.

Endnotes

[i] Afghanistan Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan 2024. UNOCHA, December 2023. Available at: https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/afghanistan/afghanistan-humanitarian-needs-and-response-plan-2024-december-2023-endarips#:~:text=The%202024%20humanitarian%20response%20in,and%20hygiene%20(WASH)%20needs. (Accessed on September 17, 2024).

[ii] AFGHANISTAN- Human Development Index for 2022. UNDP. Available at: https://data.undp.org/countries-and-territories/AFG#:~:text=Afghanistan's%20Human%20Development%20Index%20value,of%20204%20countries%20and%20territories. (Accessed on September 17, 2024).

[iii] “Reshaping U.S. Aid to Afghanistan: The Challenge of Lasting Progress.” Center for Strategic and International Studies. Feb 2022. (Accessed on September 17, 2024).

[iv] “U.S. to Move Afghanistan’s Frozen Central Bank Reserves to New Swiss Fund.”USIP, Sep 2022, Available at: https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/09/us-move-afghanistans-frozen-central-bank-reserves-new-swiss-fund (Accessed on September 17, 2024).

[v] “Afghanistan’s Herat province hit by third earthquake in nearly a week.” Al Jazeera, October 15, 2023. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/10/15/afghanistans-herat-province-hit-by-third-earthquake-in-nearly-a-week. (Accessed on September 18, 2024).

[vi] “Severe flooding in Afghanistan escalates humanitarian needs.”IFRC, May 15, 2024. Available at: https://www.ifrc.org/press-release/severe-flooding-afghanistan-escalates-humanitarian-needs (Accessed on September 18, 2024).

[vii] “Why Pakistan Is Deporting Afghan Migrants.” Council on Foreign Relations, December 15, 2023. Available at: https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/why-pakistan-deporting-afghan-migrants (Accessed on September 18, 2024).

[viii] AFGHANISTAN- Complex Emergency: FACT SHEET, USAID, June 14, 2024. Available at: https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2024-06/2024-06-14_USG_Afghanistan_Complex_Emergency_Fact_Sheet_3.pdf (Accessed on September 18, 2024).

[ix] “Why Pakistan Is Deporting Afghan Migrants.”Op.cit.

[x] Afghanistan Welfare Monitoring Survey, World Bank, October 2023. Available at: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/975d25c52634db31c504a2c6bee44d22-0310012023/original/Afghanistan-Welfare-Monitoring-Survey-3.pdf (Accessed on September 18, 2024).

[xi] WFP at Glance. UNWFP August 2, 2024. Available at: https://www.wfp.org/stories/wfp-glance#:~:text=Funding%20shortfall%20and%20ration%20cuts,insecure%20communities%20and%20saving%20lives. (Accessed on September 18, 2024).

[xii] “Afghanistan: WFP forced to cut food aid for 2 million more.”WFP, September 5, 2023. Available at: https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/09/1140372 (Accessed on September 18, 2024).

[xiii] “Afghanistan Humanitarian Response Plan 2023”. UNOCHA. Available at: https://fts.unocha.org/plans/1100/summary (Accessed on September 18, 2024).

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Afghanistan Humanitarian Response Plan 2024. Available at: https://fts.unocha.org/plans/1185/summary (Accessed on September 18, 2024).

[xvi] Secretary General’s Report on the Response to the Implications of Afghanistan for the OSCE Region (RIAOR). US Mission to the OSCE. July 25, 2024. Available at: https://osce.usmission.gov/secretary-generals-report-on-the-response-to-the-implications-of-afghanistan-for-the-osce-region-riaor/#:~:text=The%20United%20States%20is%20committed,%242.1%20billion%20since%20August%202021.

[xvii] AFGHANISTAN- Complex Emergency: FACT SHEET, USAID, June 14, 2024. Available at: https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2024-06/2024-06-14_USG_Afghanistan_Complex_Emergency_Fact_Sheet_3.pdf(Accessed on September 18, 2024)

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] “Qatar Announces Additional USD 25 Million Pledge to Support Humanitarian Response in Afghanistan.” Qatari Foreign Ministry, March 31, 2022. Available at: https://mofa.gov.qa/en/qatar/latest-articles/latest-news/details/1443/08/28/qatar-announces-additional-usd-25-million-pledge-to-support-humanitarian-response-in-afghanistan (Accessed on September 18, 2024).

[xx] “Why Don't Rich Muslim States Give More Aid to Afghanistan?” VoA, Oct 27, 2022. Available at: https://www.voanews.com/a/why-don-t-rich-muslim-states-give-more-aid-to-afghanistan-/6808495.html (Accessed on September 18, 2024).

[xxi] “Afghanistan’s humanitarian crisis: The politics of the looming disaster.” ORF, March 1, 2022. Available at: https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/afghanistans-humanitarian-crisis (Accessed on 23. 9.2024)

[xxii] “Pakistan pledges $28m in Afghanistan humanitarian support”. Al Jazeera, 23 Nov 2021. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/11/23/pakistan-pledges-28-million-in-afghanistan-humanitarian-support (Accessed on September 23, 2024).

[xxiii] “IRCS provides assistance to Afghan people through a fresh consignment of humanitarian aid.” Reliefweb, 13 Oct, 2023. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/afghanistan/ircs-provides-assistance-afghan-people-through-fresh-consignment-humanitarian-aid (Accessed on September 23, 2024).

[xxiv] “Iran's 2nd Humanitarian Aid Shipment Reaches Mazar-e-Sharif.” Tolo News, May 26. 2024. Available at: https://tolonews.com/afghanistan-188972 (Accessed on September 23, 2024).

[xxv] “Kazakhstan donates over $400 million to Afghanistan in 2023” The Khaama Press Agency, 26 December 2023.Available at: https://www.khaama.com/kazakhstan-donates-over-400-million-to-afghanistan-in-2023/.

[xxvi] “Uzbekistan provides 3,700 tons of humanitarian aid to Afghanistan.” Global Times, Dec 25, 2021. Available at: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202112/1243330.shtml (Accessed on September 23, 2024).

[xxvii] “China offers $31m in emergency aid to Afghanistan.” BBC, September 9, 2021. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-58496867 (Accessed on September 23, 2024).

[xxviii] “India Coordinating Humanitarian Assistance In Afghanistan: Centre” NDTV, March 8, 2024. Available at: https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/india-coordinating-humanitarian-assistance-in-afghanistan-centre-5201082 (Accessed on September 24, 2024).

[xxix] “India Makes New Commitment to Supply 20,000 MT of Wheat to Afghanistan.” The Wire, March 7, 2023. Available at: https://thewire.in/diplomacy/india-afghanistan-wheat-supply-new-commitment. (Accessed on September 24, 2024).

[xxx] “In a first since Taliban takeover, India to deliver aid to Afghanistan via Chabahar port.” Wion, March 7, 2023. Available at: https://www.wionews.com/india-news/in-a-first-since-taliban-takeover-india-to-deliver-aid-to-afghanistan-via-chabahar-port-569704 (Accessed on September 24, 2024).

[xxxi] “India Delivers fresh Batch of medical supplies to Afghanistan”. Mint.com, October 11, 2022. Available at: https://www.livemint.com/news/world/india-delivers-fresh-batch-of-medical-supplies-to-afghanistan-11665476982780.html (Accessed on September 24, 2024).

[xxxii] “Navigating the Ethical Dilemmas of Humanitarian Action in Afghanistan”. UK Humanitarian Innovation Hub Report, June 2023. Available at: https://humanitarianoutcomes.org/sites/default/files/publications/ho-ukhih_afghanistan_final_6_21_23.pdf.

[xxxiii] “Taliban bans female NGO staff, jeopardizing aid efforts.” Reuters, Dec 25, 2022. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/taliban-orders-ngos-ban-female-employees-coming-work-2022-12-24/ (Accessed on 24. 9.2024).

[xxxiv] “UN and top aid officials slam Afghan rulers’ NGO ban for women.” United Nations News, December 29, 2022. Available at: https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/12/1132082 (Accessed on September 24, 2024).

[xxxv] “Afghan Geneva Mission: Islamic Emirate Interfering with Aid.” Tolo News, March 17, 2023. Available at: https://tolonews.com/afghanistan-182529. (Accessed on September 24, 2024).

[xxxvi] “The Taliban Are Abusing Western Aid.” Foreign Policy, December 30, 2022. Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/12/30/taliban-western-aid-misogyny-women-rights/ (Accessed on September 24, 2024).

[xxxvii] Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) Report, SIGAR January 30, 2024. Available at: https://www.sigar.mil/pdf/quarterlyreports/2024-01-30qr.pdf. (Accessed on September 24, 2024).

[xxxviii] Afghanistan Economic Monitor. The World Bank, March 28, 2023. Available at: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/3157ea4d9d810356476fca45ef1e9370-0310012023/original/Afghanistan-Economic-Monitor-March-28-March-2023.pdf.

[xxxix] Ibid.

[xl] “Analysing Taliban’s Budget Expenditures and Revenues: Understanding the Regime’s Policies and Priorities”. Peace Rep, Available at: https://peacerep.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/PeaceRep-Afghanistan-Research-Network-Reflection_04.pdf.