Indian Council of World Affairs

Sapru House, New DelhiAnalyzing Pakistan-China Relations in 2024: Identifying Weak Points and Challenges to the All-Weather Friendship

Abstract: Pakistan and China have shared a deep bond of ‘all-weather’ partnership over decades based on geo-political interests. This paper argues that the current shifts in geopolitics and global tumult especially the sharpening US-China rivalry are making their dent on this relationship which is arguably past its days of glory.

Introduction

In 2024, Pakistan and China entered its 73rd year of diplomatic relations and eleventh year of being ‘all-weather’, or, comprehensive strategic partners (CSP). While both countries commemorated this year through small level celebrations at different points, two high level visits between China and Pakistan took place.

Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif was in China for a state visit from 4–8 June 2024. 23 Memoranda of Understandings (MoUs) on various aspects of the “All-Weather Strategic Cooperative Partnership” were signed at the end of the five-day visit.[i] Pakistan’s Information Minister, Attaullah Tarar, claimed the visit was “extremely successful and historic,” with many others noting it to be a “milestone.” This was particularly so as both countries looked at renewing the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the pioneering project of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that completed a decade of its launch in 2023. Additionally, on 14 October 2024, Chinese Premier Li Qiang reached Islamabad for a four days official trip. It was his first visit to Pakistan as the Premier. The agenda was to attend the 23rd Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Summit and conduct bilateral meetings. As the Joint Statement between China and Pakistan noted, 13 documents related to cooperation on various fronts were exchanged between the two.[ii] Amidst growing attacks on Chinese nationals and envoys in Pakistan, the arrival of Premier Qiang in particular, was backed by extremely tight security. The highlight of the visit was the inauguration of the New Gwadar International Airport, a part of CPEC, which has thus far seen delays due to security concerns. Indeed, CPEC, said to be a “game-changer,” lies at the heart of the current Pakistan-China relationship, which has progressed over time. Yet, if the China-Pakistan relationship is critically analyzed, there are clear indications of weakening of the relationship, despite the claims that it continues to be “solid as a rock” and “unshakable as a mountain.”

This paper begins with a brief overview of the Pakistan-China relationship and explores some of the evidences that point towards a weakening of the bond between the two “iron brothers.” It goes on to bring out the major challenges for both Pakistan and China in the coming times. In doing so, it argues that the relationship is very high on enthusiasm, polemics, and optics, but is not based on the operationalization of the vision of “win-win” cooperation that CPEC is supposed to signify. Rather, while Pakistan sees China as its strongest ally in Asia, Beijing increasingly looks at Islamabad as a pawn in its game of global strategic vision.

Brief Overview

In 1950, Pakistan was the first Islamic and the third non-communist country to recognize the newly created People’s Republic of China (PRC). This fact played to Pakistan’s advantage when dealing with China in the initial years and beyond. In the 1950s, the Chair of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP/CPC), Mao Tse Tung, worked towards having good relations with Pakistan, despite Pakistan having joined alliances such as the South East Asian Treaty Organization (SEATO, also referred to as the Manila Pact) in 1954 and the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO, formerly the Bagdad Pact) in 1955.[iii] Essentially, these Cold-War-time groups were against the communist bloc led by the Soviet Union, of which China was part. That Pakistan was closer to the West, especially the US, is a well-established fact. It was the Bandung Conference in April 1955, which provided an opportunity for the first time for the Pakistani Prime Minister, Mohammed Ali Bogra, to meet the Chinese Premier, Zou Enlai, and express their willingness to strengthen bilateral ties. The two countries did not delay in following this up with meaningful engagements that defined the deepening bond between Pakistan and China. In October 1956, Prime Minister Hussain Sayeed Suharwady became the first of the Heads of Government (or Head of State) from Pakistan to make an official visit to China. In two months, Zou Enlai went to Pakistan, as part of his historic tour to Asian and African nations.[iv] But, it is Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s visit to China in February 1963, as the Foreign Minister of Pakistan, that is considered foundational for the modern relationship based on “mutual trust.” This visit culminated in the Sino-Pakistan Boundary Agreement[v] between the two countries, as a result of which Pakistan ceded 2050 square miles (5300 square kilometres) of the Shaksgam Valley (part of the Trans Karakoram tract in Kashmir) to China.[vi] This removed all differences on the border issue between Pakistan and China, a subject that is of great value to Beijing.

When contextualised, this closeness in the Pakistan-China relationship was influenced by three complicating geopolitical factors of the time. First, the 1962 China-India war was a big reason for Beijing to draw close to Islamabad. As both countries had border disputes with India, they found convergence in facing a common opponent. Second, Pakistan was becoming frustrated with the US in the context of its Kashmir dispute with India. It was China that supported Pakistan openly during its war with India in 1965, providing military supplies at a time when the US pulled back from doing so.[vii] Further, immediately after Zou Enlai’s 1956 visit to Pakistan, the Premier declined an invitation by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to visit Srinagar in Kashmir, during the Premier’s visit to India (as a part of the Asian and African nations tour). Third, China’s growing distance from the Soviet Union, largely originating from ideological differences, led to Moscow supporting New Delhi in the India-China War of 1962. While China’s relations soured with the Soviet Union, leading to a border conflict between them by 1969, Beijing felt isolated and accepted Islamabad’s outreach to become close partners.

An analysis of Pakistan-China relations in the 1950s and 1960s points towards a feature that can be seen reasserting itself in the current context. It is a fact that while both China and Pakistan have sought to cement their ties for various reasons, it is Islamabad that is keener to woo Beijing, which visibly gains more in the relationship. While CPEC and its debt burden on Pakistan is a widely debated topic about the skewed China-Pakistan relationship today, references from the past can be found that are reflective of this position. In a conversation that Pakistani Ambassador to China, Sultanuddin Ahmad, had with Zou Enlai in January 1956 (excerpts of which have been produced later), he stated that Pakistanis were “very displeased” and “opposed to the Manila Pact.” [viii] The apologetic approach of Ambassador Ahmad in Beijing, who felt it was his duty to “come in person and informally”[ix] discuss with the Chinese Premier Pakistan’s position on SEATO (he also thanked China for its support for Kashmir), shows that Islamabad was worried about upsetting Beijing, even in the early days of their relationship, especially vis-à-vis its foreign policy with the West (especially the US). Further, if one studies the process of the 1963 border agreement between China and Pakistan, it is not difficult to note the conciliatory Pakistani attitude towards China. Even though China had earlier brushed aside a request by President Ayub Khan seeking clarification on the border demarcations between the two countries, Pakistan was eager to have “friendly negotiations” based on consensus with China.[x] In their desire for friendship, Pakistan went too far to appease China by handing over Shaksgam Valley in return for 750 square miles of Chinese-administered territory in 1963.

For China, Pakistan has been the important “southwestern gate,” one that allows it to connect its less-developed Xinjian province to the Arabian Sea. The construction of the Karakoram Highway became a mark of friendship between China and Pakistan. For China, the highway became a starting point for its BRI projects in Pakistan and proved to be a strategic asset to enter Pakistan. In the late 1970s, Pakistan’s connectivity with China opened up better avenues of trade. By then, the relationship had gained more depth. In 1971, China supported Pakistan in its war with India. Pakistan, on its part, supported the membership of the PRC as the sole representative of China at the United Nations. Pakistan also mediated between China and the US, most notably by facilitating the secret visit of Henry Kissinger to China in 1971. The Sino-US rapprochement released much of Islamabad’s geopolitical tensions.

In the next three decades, from the 1980s to the 2000s, Pakistan managed to raise its global strategic profile as an important South Asian country within the Muslim world. This was important for China as well as the West. China and Pakistan began to engage with each other through various formats and mechanisms, cooperating over issues ranging from military, economic, nuclear, defence, cultural and so on. The 1986 civil nuclear cooperation between China and Pakistan, the co-production of JF-17 fighter aircraft from 1999, the 2003 preferential trade agreement and the 2006 Free Trade Agreement, the 2005 Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Good Neighbourly Relations and many more such agreements are testimony to the burgeoning China-Pakistan relations. The nature of the relationship progressed from “friendly relations” up to the 1970s to “traditional friendship” in the 1980s to “comprehensive friendship” in the 1990s to “all-weather friendship,” the term being used for the first time in the 2003 Joint Declaration on Direction of Bilateral Cooperation. From the mid-2000s on, the relationship began to be defined as a “bilateral strategic partnership of good-neighbourly friendship,” until 2013, when it was elevated to an “all-weather strategic cooperative partnership.”[xi]

The China-Pakistan bilateral relationship in the decade from 2013 to 2023 can be understood very well by focusing on the growth of CPEC. It is during this decade that China, under President Xi Jinping, pushed forth its global vision of overcoming a century of humiliation and of achieving the Chinese dream via the two centenary goals, i.e. becoming a moderately prosperous nation by 2021 and for China to be a “modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, civilised and harmonious” by 2049. It was to achieve this vision that China conceptualised BRI. China found its greatest supporter in South Asia in Pakistan. It may be noted that Pakistan joined the BRI in 2015, but CPEC was conceptualised in 2013. This indicates that China was clear about its plans with Pakistan before it conceptualised other aspects related to BRI.

Given the importance of CPEC in the Pakistan-China relationship, it is crucial to analyse it to understand the current Pakistan-China relations. The Joint Statement released during the third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in October 2023 noted that both countries are on the path of building an “even closer” China-Pakistan community with a shared future in the new era through building CPEC as a “growth corridor, a livelihood corridor, an innovation corridor, a green corridor and an open corridor.” [xii] Under the CPEC banner, 42 projects had been listed in its first phase, amounting to an investment of about $40 billion from China. This amount went up to more than $60 billion eventually. By 2018, when the long-term plan for CPEC (2017–2030) was already in action, 22 of the projects amounting to $18.9 billion were reportedly completed.[xiii] What, however, needs to be scrutinized is the lag in what is being touted as a great success story and a driving force of current Pakistan-China relations on one hand and the reality on the other hand, that shows dents into the relationship, many of which pertain to problems related to CPEC and the crumbling edifice of Pakitan’s polity and economy.

Identifying Weak Points

In more than seven decades of the Pakistan-China relationship, both countries have consistently supported each other throughout its modern history, including at testing times. As such, there is a general acceptance, even among critics of the relationship, of the deep bond that Pakistan and China share. Yet, in global politics that is largely based on a realist approach, each country seeks to maximise its national interests in a world that has many complex problems. China and Pakistan are no exceptions. Like all other relations, problems exist between the two countries as well. While overtly, China and Pakistan seem to be drawing closer, particularly due to geo-strategic compulsions, at present, two major weak points can be identified in the relationship.

Complicated CPEC

As noted earlier, CPEC has become a core of Pakistan-China relations. It is not just connectivity and infrastructure projects in the hard sense that comprise CPEC. CPEC evolved to encompass cooperation in the fields of industrial development, people-to-people links, information technology, agriculture and many more aspects. In 2024, CPEC is said to have “effectively promoted Pakistan’s economic and social development since its launch 10 years ago by bringing in 25.4 billion dollars of direct investment, 236 thousand jobs, a 510-kilometre expressway, more than 8,000 megawatts of power and 886 MW of core power transmission grid.” [xiv] Yet, after a decade, there are many causes of dissatisfaction.

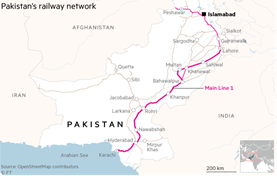

In Pakistan, when PM Sharif went to China for his visit in June 2024, media reports pinned hopes on the announcement of some new projects that would bring investments into an economically faltering Pakistan. That has still not happened, despite both countries projecting an era of CPEC 2.0. Even within the existing projects, many face long delays and remain far from completion. This has caused frustration as progress is slow. Take, for instance, the funding that is due for upgrading work on the Main Line-1 railway from Karachi to Peshawar since 2015 (see Image 1). ML-1 is the largest infrastructure project under the CPEC, which has doubled its cost due to delays,[xv] reaching an estimate of $6.86 billion. On the point on ML-1, the Joint Statement between Pakistan and China in 2023 repeated nearly the same lines as those in the 2022 Joint Statement, i.e. “recognizing that ML-1upgradation is an important project under the CPEC framework and is of great significance to Pakistan's socio-economic development, the two sides agreed to carry out the common understanding of the leaders of the two countries to implement the project at an early date.” Though the 2024 Joint Statement notes that both sides agree to implement the project in a “phased manner” and work on financing modalities, not much can be expected. This is because China has been very careful in the recent past when giving money to Pakistan. Some have pointed to donor fatigue when it comes to lending money to Pakistan, whose economic situation has gone from bad to worse in the last few years.

As per the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimate, Pakistan owed 30% of its external debt to China,[xvi] a big part of which relates to loans for CPEC projects. Pakistan is also paying relatively high interest on its loans from China. Compared to loans from Japan, Germany and France that have interest rates of 1% or lower, interest on Chinese loans varies from about 6-7% on commercial loans to 3-4% on bi-lateral loans.[xvii] The debt trap that CPEC has embroiled Pakistan in is well analysed. To assist its friend Pakistan, China provides money, especially short-term loans, and comes to rescue Islamabad when it cannot pay them back. For example, in February 2024, China reportedly agreed to roll over $2 billion in debt on existing terms after having intended to increase interest rates.[xviii] Islamabad has been unhappy about the high rate of interest, especially as toughening IMF conditionality is adding to Pakistan’s concern over CPEC projects. These issues have caused a dent in Pakistan-China relations to a great extent.

Image 1

Main line-1 of Pakistan railway network under the CPEC

Source: Financial Times, URL: https://www.ft.com/content/44c26d5c-97d2-4181-b5a4-9ef66ce776db

Economic Relations

There are arguments that claim that economic relations between Pakistan and China have taken a great turn towards strengthening the relationship in recent times. Notwithstanding the debt burden that Pakistan has already accrued since CPEC was launched, Pakistan’s trade relations with China are skewed, to say the least. At first glance, the bilateral trade volume between the two countries seems to have made great improvements over the last two decades and therefore appears to be a sign of strength for the all-weather partnership. From $4.26 billion in 2005 when the China-Pakistan Free Trade Agreement (CPFTA) was being negotiated (signed in 2006)[xix] to $16.2 billion in 2018 when Phase 2 of the CPFTA was being discussed (commenced in 2020), both countries showed an overall improvement in numbers. In 2023, the total volume was almost $20 billion. However, a closer look at this trade reveals many weak points, especially as Pakistan lags in this context. The weakest point is Pakistan’s exports to China, particularly in the service sector.

In January 2023, then Commerce Minister in the caretaker government, Gohar Ejaz, envisioned a scenario in which by 2027–28 total Pakistani exports would reach $100 billion, from the current $30 billion. This was reiterated by Planning Minister Ahsan Iqbal and Commerce Minister Jam Kamal Khan in October 2024.[xx] Even for an export-driven country, this number is not easy to achieve, let alone for Pakistan, which has not had a good record in the past, particularly when it comes to exports. From 2010 to 2018, Islamabad’s overall exports as a percentage of GDP dropped from 13.5% to 8.5%.[xxi] What matters here is the fact that Pakistan considers China the biggest potential partner in achieving such an export goal. But, even with China, exports have not risen. From $1.75 billion in 2018, it stood at $1.68 billion in 2022. Moreover, putting a reality check on it, the IMF has estimated that Pakistan’s exports will at best rise to $39.46 billion by 2028.[xxii] Added to this are the general concerns of Pakistan’s trade policy being protectionist and infrastructure being inadequate, where transportation and logistical services do not support such an ambitious goal. On the other hand, China remained Pakistan’s largest trading partner for years, steadily increasing exports that rose from $14 billion to $17.7 billion during the same period from 2018-2022.[xxiii] China’s exports complement Pakistan’s imports much more than the other way around. China also exports services to Pakistan, while in 2022, Pakistan had no trade in services to China. These add to the imbalance in trade in Pakistan-China relations that has not been corrected for years and continue to only broaden. The CPFTA-2 aims to address some of these issues. But the economic doldrums that Pakistan is in today do not give much hope for the near future.

Challenges Ahead

Drawing from the weak points in the previous section, many challenges can already be identified for the Pakistan-China relations. Discussed below are two main challenges for the all-weather friendship in the coming times.

The US Factor

One of the big challenge today, especially for Pakistan, is in dealing with the US-China global rivalry. The US and China of the 21st century have clear differences that have incrementally led to global tensions. From disputes over China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea to those over Taiwan, Hong Kong and Tibet, to the growing technological and trade wars, to geopolitical and ideological differences in global conflicts such as Russia-Ukraine or Gaza-Palestine, the US and China are at loggerheads. China is confrontational towards the US, and Pakistan, like in the 1950s, finds itself increasingly trying to strike a balance between its two partners. The US is Pakistan’s largest export market. China is its largest investor. Both the US and China provide military assistance to Pakistan and look at Islamabad as having geostrategic value, particularly given its location in South Asia, an opening to the Arabian Sea, and an important position within the Muslim world. There is no doubt that the US relationship with Pakistan is more of a transactional partnership, unlike the comprehensive strategic partnership it has with China. Yet, it is not an easy choice for Pakistan to make when choosing between the two.

Depending on the stakes, Pakistan practices fine balancing through diplomacy. In March 2023, Pakistan opted out of the virtual Summit for Democracy, co-hosted by the US, only a week after participating in the International Forum on Democracy organised in China. However, the US has great influence over the financial and multilateral institutions of the West, from where Pakistan needs money as well as approval on many matters. Pakistan needs the US’s support for the grants and funds that it continues to take from institutions like the IMF. It needs waivers on sanctions that Washington has imposed on states collaborating and trading with Iran. One reason for the delay in the Iran-Pakistan Gas Pipeline project is attributed to US pressure, for instance. Further, reportedly, in April 2024, the US sanctioned three Chinese and one Belarusian firm for supplying missile-applicable items for Pakistan’s missile programme, which the US opposes, as it remains principally committed to the global nonproliferation regime.[xxiv] At the same time, China, as the all-weather friend, does not want Pakistan to fall out of its influence and remains its supporter, including in multilateral forums. Simply put, the situation is complicated, and the challenges are only expected to grow in the near future. This is particularly true with President Donald Trump back to power in Washington. Observers have already highlighted that Trump 2.0 has many China hawks. Appointment of Mike Waltz, known to be a China critic, as the national security advisor is an indication of the administration’s approach towards Beijing. This leaves Pakistan in a more difficult situation. As it is, during his earlier Presidency, Donald Trump had accused Pakistan of ‘deceit and lies’ on issues pertaining to countering terrorism and had threatened to cut aids. This time, Pakistan has been quick to make friendly overtures to the White House, reflecting on the growing anxiety that Islamabad habours. What else explains Pakistani PM, Shebaz Sharif’s alleged breach of law to congratulate President Trump on X by using Virtual Private Network (VPN), despite the app being banned in Pakistan?

In an interview in June 2024, Graham Allison noted that after the meeting in San Francisco in 2024 between President Xi Jinping and President Joe Biden, the US and China have laid some ground rules, as per which three things are expected between the two big powers: fierce competition, communications and unavoidable cooperation.[xxv] Given the recent developments, the US-China relationship is expected to become more unpredictable and competitive, making it more challenging for Pakistan to balance global geopolitics. It can be said that rising US-China rivalry is, as per current trends, shrinking Pakistan’s diplomatic space and is further expected to adversely affect the leverage that it traditionally enjoyed in a geopolitical sense especially with the US.

Security and CPEC

Another glaring challenge pertaining to CPEC is its security aspect. The number of attacks on Chinese nationals (those working on CPEC projects) as well as protests over Chinese projects, especially in Balochistan province, have become bones of contention between the two iron brothers. The December 2022 protests in Gwadar over socio-economic problems caused by CPEC projects is only a small part of a graver problem. The increasing attacks on Chinese nationals and officials in Pakistan is the biggest concern for China at the moment. Attack on a convoy on 13 August 2023 that was carrying Chinese citizens near the Gwadar port; the death of five Chinese nationals on 26 March 2024 as a result of a suicide bombing near the Daso hydropower project; the terrorist attack on 6 October 2024, on a convoy of Chinese project near the Jinnah International Airport in Karachi, which killed 2 Chinese are just a few mentions. The Chinese reaction to the issue has now moved from showing concern to giving assertive advice on how Islamabad needs to handle the situation with firm hands. In the 2024 Joint Statement, as well as a message from Chinese Ambassador to Pakistan, Jian Zaidong, in April 2024, the Daso incident have been highlighted along with the note to “hunt down the perpetrators” and give “severe punishment.” As China has linked the CPEC to its Global Security Initiative (GSI), Pakistan’s inability to handle such terrorist attacks is now being seen as a big challenge in the bilateral relationship.

Conclusion

After the visit by PM Sharif to China in June 2024, many observers have pointed out the hype of the Pakistan-China relationship, which has arguably gone past its days of glory. In an article published in The Diplomat on 13 June 2024, Eram Ashraf compares the 2024 Joint Statement between Pakistan and China with three others — 2018, signed after PM Imran Khan visited China;[xxvi] 2022, signed after PM Shehbaz Sharif visited China;[xxvii] and 2023, signed after interim PM Anwar-ul-Haq Kakkar’s visit. In the 2024 document, the official phrase used to describe the friendship remains “all-weather strategic cooperative partnership.” But, in both the 2023 and 2024 documents, Pakistan is considered to be “a priority” in China’s foreign relations, from being the “highest priority” just a few years earlier. For Pakistan, its relations with China continue to be “the cornerstone of its foreign policy.”[xxviii] In her assessment of the article, the author suspects a possibility of China “downgrading” its relations with Pakistan. While that may be an exaggerated prediction, it supports the argument made in this paper that it is Pakistan that considers its friendship with China indispensable and values it more than the other way around. Given this equation between Pakistan and China, one that is skewed in favour of China, it is not surprising to expect more challenges to the nature of the relationship in the coming years as well as changes that reflect on the weakening of the relationship.

*****

*Dr. Shrabana Barua is an Associate Professor at Jindal School of International Affairs (JSIA), O.P. Jindal University. She is a former Research Fellow at the Indian Council of World Affairs, New Delhi.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are personal.

Endnotes

[i] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, People’s Republic of China, ‘Joint Statement between the People’s Republic of China and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan,’ June 07, 2024, URL: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/wjdt_665385/2649_665393/202406/t20240609_11415903.html#:~:text=The%20Chinese%20side%20reiterated%20its,and%20prosperity%2C%20in%20firmly%20combating.

[ii] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, People’s Republic of China, ‘Joint Statement between the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and the People’s Republic of China,’ 15 October 2024, URL: https://www.mfa.gov.cn/eng/xw/zyxw/202410/t20241016_11508330.html#:~:text=Mr.%20Li%20Qiang%2C%20Premier%20of,Cooperation%20Organization%20chaired%20by%20Pakistan.

[iii] See Masood Khalid, ‘Pakistan-China Relations in a Changing Geopolitical Environment,’ November 30, 2021, ISAS Working Papers, National University of Singapore, URL: https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/papers/pakistan-china-relations-in-a-changing-geopolitical-environment/.

[iv] Ministry of the Foreign Affairs, People’s Republic of China, ‘Premier Zhou Enlai's Three Tours of Asian and African countries’, (n.d.), URL: https://www.mfa.gov.cn/eng/zy/wjls/3604_665547/202405/t20240531_11367543.html.

[v] Copy of the boundary agreement between China and Pakistan 1963, URL:https://www.scribd.com/document/326874487/China-Pakistan-Boundary-Agreement-1963.

[vi] This is not recognised by India, as Shaksgam is a part of the territory of Jammu and Kashmir of India. This transfer is therefore considered illegal and as a violation of India’s sovereignty. The maps used in the agreement between China and Pakistan were published in the tenth and eleventh issues of the Peking Review on 15 March 1963.

[vii] Klaus H. Pringsheim, ‘China's Role in the Indo-Pakistani Conflict’, The China Quarterly, No.24, Oct-Dec 1965, pp.170-175URL:

[viii] ‘Abstract of Conversation: Premier Zhou Enlai and Pakistani Ambassador Sultanuddin Ahmad’, Wilson Center, Digital Archive, January 04, 1956, URL: https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/abstract-conversation-between-chinese-premier-zhou-enlai-and-pakistani-ambassador-china.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Interview by Ambassador Naghmana Hashmi, ‘Will China continue to support Pakistan in the future?’, How does it work podcast, June 18, 2024, URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9umzxESu6Wo.

[xi] See Masood Khalid, 2021.

[xii] Joint Press Statement between the People's Republic of China and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, The Third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, 2023, URL: http://www.beltandroadforum.org/english/n101/2023/1024/c127-1314.html.

[xiii] Latest progress on the CPEC, Embassy of the People’s Republic of China, December 29, 2018, URL: https://www.google.com/search?client=safari&rls=en&q=Latest+progress+on+the+CPEC%2C+Embassy+of+the+People’s+Republic+of+China%2C+December+29%2C+2018&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8.

[xiv] H.E. Jiang Zaidon, Ambassador of the PRC to the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, ‘Implement a Holistic Approach to National Security, Write a Security Chapter in Building the China-Pakistan Community With a Shared Future,’ April 2024, URL:

[xv] Syed Irfan Raza, ‘ML-1 cost more than double due to delay, PM told,’ Dawn, June 14, 2023, URL: https://www.dawn.com/news/1759584.

[xvi] International Monetary Fund, ‘Pakistan: Request for a Stand-by Arrangement-Press Release; Staff Report; Staff Statement; and Statement by the Executive Director for Pakistan,’ July 18, 2023, URL: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2023/07/17/Pakistan-Request-for-a-Stand-by-Arrangement-Press-Release-Staff-Report-Staff-Statement-and-536494.

[xvii] Amit Bhandari, ‘Understanding Pakistan’s China debt problem,’ Gateway House, June 22, 2022, URL: https://www.gatewayhouse.in/understanding-pakistans-china-debt-problem/. See also, Jonathan E. Hillman, ‘Infrastructure and Influence: The Strategic Stakes of Foreign Debt,’ January 2019, A Report of the CSIS Reconnecting Asia Project, Center for Strategic and International Studies.

[xviii] Shahbaz Rana, ‘China agrees to roll over $2 billion loan on existing terms,’ Tribune Pakistan, 28 February 2024, URL: https://tribune.com.pk/story/2457855/china-agrees-to-rollover-2b-debt-on-existing-terms.

[xix] Ministry of Commerce, Islamic Republic of Pakistan, Pakistan China Free Trade Agreement in Goods and Investments, URL: https://www.commerce.gov.pk/about-us/trade-agreements/pak-china-free-trade-agreement-in-goods-investment/.

[xx] Mubarak Zeb Khan, ‘Govt eyes $100bn exports without outlining roadmap’, Dawn, 9 October 2024, URL: https://www.dawn.com/news/1863975.

[xxi] World Bank, ‘The China Pakistan Economic Corridor and the Growth of Trade,’ URL: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/674251583850888285/pdf/The-China-Pakistan-Economic-Corridor-and-the-Growth-of-Trade.pdf.

[xxii] Mubarak Zeb Khan, ‘Analysis: Govt’s $100bn export plan and IMF reality check,’ Dawn, 28 January 2024, URL: https://www.dawn.com/news/1809237.

[xxiii] World Bank, ‘The China Pakistan Economic Corridor and the Growth of Trade,’ URL: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/674251583850888285/pdf/The-China-Pakistan-Economic-Corridor-and-the-Growth-of-Trade.pdf.

[xxiv] NDTV world, ‘US Sanctions Chinese, Belarus Firms For Giving Missile Tech To Pakistan’ April 20, 2024, URL: https://www.newsonair.gov.in/us-sanctions-chinese-and-belarusian-companies-for-providing-ballistic-missile-components-to-pakistan/#:~:text=The%20United%20States%20has%20imposed,Ltd.

[xxv] Graham Allison for an interview with Dewey Sim and Igor Patrick, ‘Has a Thucidides Trap been set?’, SCMP, June 03, 2024, URL: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3264540/has-thucydides-trap-been-set-political-scientist-graham-allison-gauges-risks-could-send-us-china.

[xxvi] ‘Full text of China-Pakistan joint statement’, Xinhua, November 04, 2018, URL: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-11/04/c_137581441.htm.

[xxvii] ‘Full text: Joint Statement between the People's Republic of China and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan’, Xinhua, November 03, 2022, URL: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202211/03/WS6362b5fca310fd2b29e7ff1b.html.

[xxviii] Eram Ashraf, ‘Is China Souring on Pakistan?’, The Diplomat, June 13, 2024, URL: https://www.google.com/search?client=safari&rls=en&q=is+china+souring+on+pakistan&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8.