Indian Council of World Affairs

Sapru House, New DelhiThe Growing Influence of JNIM in West Africa: Threats to Benin, Togo and Ghana

On 8 January 2025, Jama'at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) launched a deadly attack on a fortified military post in Benin's Park W, claiming the lives of at least 28 Beninese soldiers. This was reportedly the deadliest attack ever since the July 2024 attack, when the group killed 12 rangers near the Makrou River. Togo also experienced a brutal attack near Faneorgou village in northern Togo in October 2024, resulting in the death of six soldiers. Similarly, though Ghana has not experienced direct large-scale attacks, JNIM’s looming presence on its northern borders is increasingly evident.

These incidents highlight an alarming trend: Coastal West African states once considered immune from Sahelian extremism are increasingly getting entangled in a web of Sahelian extremism, particularly from terror groups like JNIM. This paper attempts to understand the expansion of JNIM in Togo, Benin and Ghana. It focuses on the historical evolution of JNIM and explores the factors responsible for its expansion and the role of regional and international cooperation in stemming the spillover of extremism from the Sahel into the coastal states of West Africa.

1. Evolution of JNIM and Its Steady Expansion

Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) is a Sahelian branch of Al-Qaeda formed in March 2017 in Mali by merging several preexistent militant groups, which included Ansar al-Din, al-Murabitun, the Macina Liberation Front (MLF) and Al-Qaeda in the lands of the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).[i] The formation of JNIM united these groups under the slogan “One banner, One group and One emir.”[ii] Iyad Ag Ghaly, the leader of Ansar al-Din, was appointed as emir of the group, which helped to give the alliance a more local profile. Strategically shifting leadership from Algeria-based AQIM to diverse representatives from local communities like Fulani, Tuareg and Arabs has helped JNIM strategically “localise” its struggle.[iii]

Since its inception in 2017 in Mali, JNIM has expanded its influence in neighbouring countries like Burkina Faso and Niger. Moving from its earliest focal point in Mali, Burkina Faso has emerged as a primary battleground in recent years. Starting from 2021, terrorism-related deaths have soared up to 6000, making up more than half of global fatalities. Burkina Faso alone has accounted for nearly 60% of jihadist-related violence in the region, with a staggering 68 percent increase in jihadist activities from 2023 to 2024, with JNIM responsible for the majority of these incidents.[iv] The violence has surged by over 50% between 2020 and 2023, displacing more than two million people and creating one of the world’s fastest-growing humanitarian crises.[v] Burkina Faso’s central location, weak state control and fragmented security apparatus have helped JNIM to establish operational hubs and expand its influence. However, the impact of these activities is not contained to Burkina Faso. From 2022, the group has started steadily expanding towards the south, threatening neighbouring coastal states.

Between 2022 and 2024, JNIM has steadily extended its influence into coastal African states.[vi] In Togo, Benin and Ghana, JNIM’s operations have escalated alarmingly. Attacks in these countries have increased by more than 250%, with a significant rise from 21 in 2022 to 53 in 2024, with many incidents reported in the border areas near Togo and Benin.[vii]

‘Benin’, particularly, has become a significant target due to its proximity to Burkina Faso. The number of extremist attacks in Benin surged dramatically, from 71 in 2022 to 171 in 2023, underscoring the growing foothold of JNIM.[viii] Similarly, Togo also experienced an increase in militant activities, recording 14 attacks in 2023, which resulted in 66 fatalities.[ix] The attacks are likely aimed at degrading Togolese border security and strengthening its cross-border support zones. Ghana has not experienced direct large-scale attacks. However, the presence of jihadist groups is increasingly evident. JNIM is known to use northern Ghana as a logistical and medical hub, where they secure supplies and receive treatment for wounded fighters.[x]

The looming presence of JNIM in Benin, Togo and Ghana marks shift in the group’s strategy. This expansion not only threatens to destabilise the political systems of these countries but also extends the theatre of terrorism towards the coast.

2. Reasons behind JNIM’s Expansion towards the Coast

JNIM’s expansion from its stronghold in the Sahel towards coastal states like Benin, Togo and Ghana is a calculated shift in strategy driven by internal pressures in the Sahel and external opportunities in littoral states. This southward expansion reflects the group’s ability to adapt to changing dynamics in the region, which includes building pressure in its traditional territories and opportunities presented in neighbouring states.

Among the various push factors behind the expansion of JNIM is the escalating military pressure in the Sahel. Regional counterterrorism efforts, including Burkina Faso’s intensified military operations under Captain Ibrahim Traore, have disrupted JNIM’s supply lines and operational bases. For instance, the Burkinabe “Operation Laabingol”[xi] in 2022 targeted JNIM positions in Djibo and Gorom-Gorom, which displaced hundreds of fighters and forced them to seek refuge in less militarised zones.[xii] Apart from this, in response to the growing insurgency threat, Burkina Faso launched state-sponsored militias like the “Volunteers for the Defense of the Fatherland” (VDF), which recruited 50,000 civilian defence volunteers to help the army fight against jihadists.[xiii] This has rendered JNIM difficult to hold on its bases in Burkina Faso and necessitated safer operational bases in neighbouring countries.

Simultaneously, among different militant groups, the “Islamic State in the Greater Sahara” (ISGS) has emerged as a major opponent of JNIM. ISGS has increased its dominance in certain areas of the Sahel, such as Niger’s Tillaberi region, which is the tri-border region connecting Mali, Burkina Faso and Benin. This has heightened the competition between JNIM and ISGS, which further compelled JNIM to expand southwards into less congested and more vulnerable regions.[xiv]

Tilaberi Region (Niger). Source — Researchgate [xv]

Another significant push factor is the economic burden resulting from prolonged conflict in the Sahel and the impacts of climate change. Years of conflicts have depleted local resources, such as grazing lands and water points, which are essential for JNIM’s extortion-based revenue model, which involves demanding money from local communities in exchange for protection.[xvi] Consequently, coastal West Africa, with its relatively untapped resources and economic hubs, has become an attractive alternative for JNIM.[xvii]

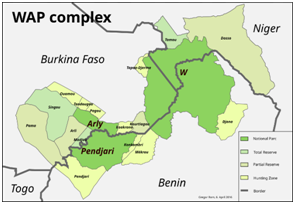

On the other hand, several strategic incentives have made coastal states a potential target for JNIM. The porous border between Burkina Faso and these states presents an opportunity for insurgents to exploit ungoverned spaces. The W-Arly-Pindjari complex has become an operational base and hideout for JNIM. Additionally, coastal states provide access to lucrative economic targets, such as trade corridors and transportation routes. These countries serve as supply or transit zones for various goods like motorcycles and act as sources of finance through the sale of stolen items for consumption.[xviii]

W-Arly-Pindjari Complex. Source – Wikipedia. [xix]

Moreover, societal marginalisation in these countries has facilitated JNIM’s expansion. For instance, in northern Benin, the marginalised Atakora region has become a fertile ground for recruitment as JNIM has been successful in exploiting local grievances against the central government. [xx]

3. National and Regional Response to Terrorism

For a long time, extremist groups in the Sahel have thrived by exploiting intercommunal fault lines to stir up social discord, weaken the trust in government, and recruit supporters. Therefore, it is crucial to understand how the coastal states have been confronting the jihadist extremism.

Benin and Togo have reacted to this threat and adopted similar approaches as their Sahelian neighbours. They have relied on measures like arrest and other abuses. This reliance on heavy measures may threaten to escalate the conflict, the same that has happened in Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali.

Benin has been the hardest hit by the recent surge in terrorist activities. As a response, Benin created an agency, “Agence Béninoise de Gestion Intégrée des Espaces Frontaliers,” to manage border areas,[xxi] which aims to combine security and developmental challenges in border communities. However, efforts to build trust with vulnerable populations have been limited and slow to deal with escalating threats. To halt the growing militant activities near its northern borders, Benin launched “Operation Mirador” in 2022. As a part of the operation, 3,000 troops have been mobilised in border areas for patrolling to counter increasing militant Islamist attacks on communities, security forces and park rangers. To improve intelligence capabilities on the ground, 1,000 local troops have been recruited. [xxii]

Benenese security forces are also working closely with nonprofit organisations like African Parks, which manages the w-Arly-Pendjari reserves under a public-private agreement. In Niger, with the advent of a military junta coming to power in the July 2023 coup, the military cooperation agreement signed between Niger and Benin in 2022, which aimed at improving cross-border security, has halted. Similarly, discussions over creating a unified management and security structure for the park complex have been put on hold.[xxiii] However, the sudden presence of the military forces has exacerbated tensions within local communities. The use of heavy-handed measures by these forces has deepened the grievances of local communities with the government.[xxiv]

In Togo, the government launched “Programme d’urgence pour les Savanes,” a multisectoral program of 26.6 million dollars in 2022 in its northernmost region, combining military measures with efforts to address local socio-economic grievances. The West Africa Development Bank has supported this program with an additional 50 million dollars, aiming at improving infrastructure, social service delivery and economic resilience in the region.[xxv] The reports of a surge in intrusion along the northern borders have developed a state of emergency after 2022.[xxvi] This has resulted in the deployment of a greater number of troops in northern Togo. Though due to the use of heavy-handed tactics, these measures have proved to be counterproductive to the objective of rapport-building between security forces and local communities.

In Ghana, the government has launched a comprehensive decentralisation programme. This includes redrawing administrative jurisdictions in the northern region and increasing the flow of investments in border security and intelligence. The government is also working for the security of communities where the presence of extremist groups is high and intercommunal tensions are present. The Ghanaian government has worked to address the inter-communal tensions between communities, which has helped reduce violence in the northern area. These efforts have demonstrated the feasibility of an effective conflict prevention strategy where extremist groups exploit socio-political fractures for their profit.[xxvii]

Apart from individual initiatives, cross-border implications of violent extremism have necessitated a coordinated response in the region. ECOWAS has conducted numerous peacekeeping operations in the region and has developed the “ECOWAS Standby Force (ESF)” as a part of the African Union peace and security architecture. However, a surge in violence has revealed myriad challenges in mobilising its forces in recent years.[xxviii]

Apart from this, the Accra Initiative is the most important regional security initiative. It was started in 2017 with five members — Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire Ghana and Togo — to combat the spread of violent extremism, prevent terrorist attacks and address transnational organised crime within their territories. Mali and Niger joined it in 2020, and Nigeria has maintained observer status since April 2022. Under the Accra initiative, operations like Koudanlgou I and II were carried out. However, coordination challenges and limited resources hindered the achievement of significant outcomes. [xxix]

Conclusion

Coastal West African countries like Benin, Togo and Ghana are becoming hotspots of violent extremism due to JNIM’s strategic southward expansion. These countries face challenges similar to those in the Sahel, such as porous borders, ungoverned territories, and limited state presence. Togo, Benin and Ghana have intensified their counterterrorism efforts through various initiatives. Benin launched “Operation Mirador and created an agency for border management. Similarly, Togo implemented “Programme d’urgence pour les Savanes,” which combined military and development measures. Ghana’s decentralisation program and efforts to address inter-communal tensions in the north have tried to mitigate the extremist threat. However, despite these intensified counter-terrorism efforts, structural vulnerabilities in both Sahel and coastal states continue to fuel this spread. At the regional level, initiatives like the “Accra initiative” and localised security programmes have shown potential; still, their impact remained constrained due to resource limitations, heavy-handed tactics and insufficient community engagement. These challenges highlight the need for a cross-littoral program between Sahel and coastal states — one that balances security operations with socio-economic development in both Sahel and coastal states. A coordinated and context-sensitive strategy for both the Sahel and coastal states is crucial to addressing the root causes of extremism and preventing its further spread across West Africa.

*****

*Ingale Utkarsh Ajay, Research Intern, Indian Council of World Affairs, New Delhi

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal.

Endnotes

[i] ‘Jamat Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin’. National Counter Terrorism Centre. https://www.dni.gov/nctc/ftos/jnim_fto.html.

[ii] @MENASTREAM. X. Twitter. March 02, 2017. MENASTREAM on X: "Video with formalizing statement on the creation of 'Jama'a Nusrat ul-Islam wal-Muslimin' released "[under]one banner, one group, one emir" https://t.co/5k7HJUtni0" / X.

[iii] Alexander Thurston. ‘Jihadists of North Africa and the Sahel: Local Politics and Rebel Groups’. Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/jihadists-of-north-africa-and-the-sahel/C1C391EC226A65858CCF45322879ED1B.

[iv] Global Terrorism Index 2024. Institute for Economics and Peace. https://www.economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/GTI-2024-web-290224.pdf.

[v] ‘Burkina Faso: Upsurge in Atrocities by Islamist Armed Groups’. Human Rights Watch. June 15, 2023. https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/06/15/burkina-faso-upsurge-atrocities-islamist-armed-groups?form=MG0AV3.

[vi] Daniel Eizenga. ‘Recalibrating Coastal Africa’s Response to Violent Extremism’. Africa Centre for Strategic Centre. July 22, 2024. https://africacenter.org/publication/asb43en-recalibrating-multitiered-stabilization-strategy-coastal-west-africa-response-violent-extremism/#:~:text=A%20spike%20in%20militant%20Islamist,events%20over%20the%20same%20period.

[vii] R.Maxwell Bone. ‘Islamists Extremists are Threat to Ghana, Benin and Togo. Foreign Policy.

September 04, 2024. https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/09/04/ghana-togo-benin-burkina-faso-jihadists-jnim/.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] 'In Ghana, Sahel jihadis find refuge and supplies, sources say'. Reuters. October 26, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/ghana-sahel-jihadis-find-refuge-supplies-sources-say-2024-10-24/

[xi]Operation Laabingol. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Laabingol?form=MG0AV3

[xii] Doukhan, David. JNIM (Jama’at Nusrat ul-Islam wal-Muslimin) Continues to Expand in Mali and Burkina Faso. International Institute of Counter Terrorism. https://ict.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Doukhan_JNIM-Jamaa-Nusrat-ul-Islam-wa-al-Muslimin-continues-to-expand-in-Mali-and-Burkina-Faso_2024_16_01.pdf.

[xiii] 'Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland (VDP)'. ACLED. https://acleddata.com/2024/03/26/actor-profile-volunteers-for-the-defense-of-the-homeland-vdp/.

[xiv] 'Newly restructured, the Islamic State in the Sahel aims for regional expansion'. ACLED. https://acleddata.com/2024/09/30/newly-restructured-the-islamic-state-in-the-sahel-aims-for-regional-expansion/?form=MG0AV3.

[xv] Toudou-Daouda, Moussa. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Moussa-Toudou-Daouda/publication/322643786/figure/fig1/AS:616052228620292[at]1523889705915/The-neighboring-countries-of-Niger-and-the-different-regions-of-the-country-which-are.png.

[xvi] Eizenga, Daniel and Williams, WenDy. 'The Puzzle of JNIM and Militant Islamist Groups in the Sahel'. Africa center for strategic studies. https://africacenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/ASB-38-EN.pdf?form=MG0AV3.

[xvii] 'Non State Armed Groups and Illicit Economies in West Africa'. ACLED. https://acleddata.com/acleddatanew/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/JNIM-Non-state-armed-groups-and-illicit-economiesin-wWest-Africa-GI-TOC-ACLED-October-2023.pdf.

[xviii] Adf. ‘Motorbike trafficking drives instability throughout the Sahel’. Africa Defense Forum’. October 31, 2023. https://adf-magazine.com/2023/10/motorbike-trafficking-drives-instability-throughout-the-sahel/?form=MG0AV3.

[xix] Rom, Greor. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W-Arly-Pendjari_Complex#/media/File:WAP-Komplex_englisch.svg.

[xx] Explaining JNIM expansion into Benin. Clingendael Report. https://www.clingendael.org/pub/2022/conflict-in-the-penta-border-area/3-explaining-jnim-expansion-into-benin/?form=MG0AV3.

[xxi] Agence Béninoise de Gestion Intégrée des Espaces Frontaliers. https://www.developmentaid.org/donors/view/471017/agence-beninoise-de-gestion-integree-des-espaces-frontaliers?form=MG0AV3.

[xxii] ‘Benin Boosts Military Presence in North to Stop Cross-Border Attacks’. Africa Defence Forum. July 26, 2022. https://adf-magazine.com/2022/07/benin-boosts-military-presence-in-north-to-stop-cross-border-attacks/.

[xxiii] Eizenga, Daniel and Gnanguênon, Amandine. ‘Recalibrating Coastal West Africa’s Response to Violent Extremism’. Africa center for strategic studies. https://africacenter.org/publication/asb43en-recalibrating-multitiered-stabilization-strategy-coastal-west-africa-response-violent-extremism/.

[xxiv] Lemmi, Davide & Simoncelli, Marco. 'Benin Is the New Jihadist Front in Africa'. https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/benin-new-jihadist-front-africa.

[xxv] Eizenga, Daniel and Gnanguênon, Amandine. ‘Recalibrating Coastal West Africa’s Response to Violent Extremism’. Africa center for strategic studies. https://africacenter.org/publication/asb43en-recalibrating-multitiered-stabilization-strategy-coastal-west-africa-response-violent-extremism/.

[xxvi] africanews. 'Togo declares state of security emergency in the north'. africanews. June 14, 2022. https://www.africanews.com/2022/06/14/togo-declares-state-of-security-emergency-in-the-north/?form=MG0AV3.

[xxvii] Eizenga, Daniel and Gnanguênon, Amandine. 'Recalibrating Coastal West Africa’s Response to Violent Extremism'. Africa center for strategic studies. https://africacenter.org/publication/asb43en-recalibrating-multitiered-stabilization-strategy-coastal-west-africa-response-violent-extremism/.

[xxviii] Kohnert, Dirk. 'ECOWAS, once an assertive power in West Africa, reduced to a paper tiger?’ https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/118241/.

[xxix] ADF. 'Accra Initiative Takes Aim at Extremism’s Spread'. Africa Defence Forum. December 13, 2022. https://adf-magazine.com/2022/12/accra-initiative-takes-aim-at-extremisms-spread/.