Indian Council of World Affairs

Sapru House, New DelhiEnergy Dynamics in EU-Central Asia Relations: A Review

Abstract

The EU remains the largest energy consumer after the US and China. EU’s overall dependence on the imports of energy resources stands at 55% of total consumption. The Central Asian region, especially Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, are rich in energy resources, which for most parts is still untapped. Energy cooperation between EU and Central Asia has enhanced from exports to the promotion of sustainable development of energy resources and capacity building. The paper would analyse the EU’s engagement with Central Asian countries and look at their energy relations and how this region can play a crucial role in EU’s quest for diversification of its energy sources.

Introduction

Central Asia’s strategic geographical location, at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, has made this region an important partner for the European Union (EU). The Central Asian region, especially Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, are rich in energy resources, which for most part are still untapped. With energy security, need for diversification of sources and capacity building rising in importance in recent years, the EU is looking towards this region with renewed interest. Although relations between the two date back to the 1990s, the EU with its recently published Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council on the EU’s Strategy on Central Asia (May 2019) is trying to re-energise relations, specially in the field of energy. This was highlighted in the strategy where the EU called for the intensification of relations with Central Asian countries in order to assist its efforts at energy source diversification. According to the strategy, “Energy cooperation between EU and Central Asia centres around promoting sustainable development of energy resources, diversification of supply routes, exchange of know-how, to the actual development and use of new energy sources, especially of renewable energy”.

Overview of EU’s Engagement in Central Asia

The partnership and cooperation agreements (PCAs) and, enhanced partnership and cooperation agreements (EPCAs) remain the cornerstone of the EU’s engagement in Central Asian countries. EU has signed PCAs with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. It signed PCA with Turkmenistan but it has not yet been ratified by the European Parliament. With regard to the EPCAs, it has only been signed with Kazakhstan and negotiations are underway with Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. EU’s relations with Central Asian countries were defined through the Union’s 2007 Strategy on Central Asia. This strategy underlined six priorities of the EU in the region – these included protecting human rights; responding to security threats; development of transport and energy links; economic development; youth and education; and environment and water. The policy was updated in 2019, and the focus was on three interconnected priorities – first, partnering for resilience, where EU would partner with the Central Asian countries to address challenges related to socio-economic goals and to enhance their ability for reforms and modernisation; second, partnering for prosperity, to enhance their growth potential and develop competitive private sector; and third, working better together, so as to strengthen the architecture of the partnership, increasing civil society participation and improving political dialogue.1

The EU is Central Asia’s biggest economic partner accounting for almost 30% of the region’s total trade and direct investments worth €62 billion. Kazakhstan is the largest trading partner of the EU in the region, with its oil sector accounting for almost 85% of its exports to the EU and is also the largest recipient of the EU direct investment. Central Asian countries receive funding from the Union through its Development Cooperation Instrument. This assistance largely focuses on regional security, education, economic-development, sustainable management of natural resources etc. The assistance for Central Asia has increased over the years with the region receiving €1.1billion for 2014-2020 as compared to €675 million for 2007-20132. Also, European Bank of Reconstruction and Development and the European Investment Bank provide financial support to the Central Asian countries. Between the two institutions, they have invested €11.3 billion in the region.3 Another key initiative launched by the European Union is ‘Central Asia Invest’ programme, which was set up in 2007. This initiative aims to stimulate and support the small and medium sized enterprises in the region by promoting policies which facilitate investments, open new markets, and strengthen competitiveness.4

Energy Resources in Europe and Central Asia

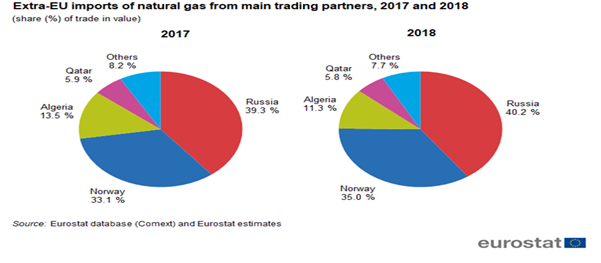

The EU remains the largest energy consumer after the US and China. EU’s overall dependence on the imports of energy resources stands at 55% of total consumption. The most pressing situation is with oil where the total import dependency is of 87%, whereas for the natural gas imports it is 70%, followed by other fossil fuels where the dependency percentage ranges to 42%.5 Russia remains the largest supplier of the natural gas to the EU for the years 2017-18 with a total share of 40.2%. Other key suppliers are Norway (35%), Algeria (11.3%) and Qatar (5.8%). (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Imports of Natural Gas to Europe

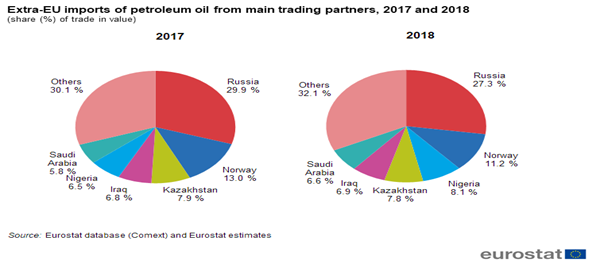

Similarly, in the supply of petroleum oils, Russia again leads the group by accounting for almost 27.3% of the total oil received, ahead of Norway with 11.2% of imports. Other key partners are Kazakhstan (7.1%), Iraq (6.9%), Nigeria (8.1%) and Saudi Arabia (6.6%)6. (Figure 2) In terms of solid fuels, almost three quarters of solid fuel (mostly coal) imports come from Russia (30%), Colombia (23%) and Australia (15%).

Figure 2: Imports of Oil to Europe

On the other hand, Central Asian countries are resource rich (Table 1). The largest oil reserves in the region are located in Kazakhstan, which holds almost 1.7% of world’s proven oil reserves. Similarly, for natural gas, Turkmenistan accounts for almost 9.9% of world’s proven reserves, followed by Uzbekistan with 0.6% and Kazakhstan with 0.5%.

Table 1: Oil and Natural Gas Resources in Central Asia

|

Country |

Oil Resources in Central Asia

|

Natural Gas Resources in Central Asia

|

||||||||||

|

Production (in million tonnes) |

Consumption (in million tonnes oil equivalent) |

Proven Reserves |

Production (in billion cubic metres) |

Consumption (in billion cubic metres) |

Proven Reserves |

|||||||

|

2017 |

2018 |

2017 |

2018 |

2017 |

2018 |

2017 |

2018 |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Kazakhstan |

87.0 |

91.2 |

6.7 |

6.8 |

1.7% |

23.4

|

24.4

|

10.6

|

10.8

|

0.5%

|

||

|

Turkmenistan |

11.2 |

10.6 |

6.9 |

7.1 |

** |

58.7

|

61.5

|

15.9

|

19.4

|

9.9% |

||

|

Uzbekistan |

2.8 |

2.9 |

2.7 |

2.6 |

** |

53.4 |

56.6 |

25.3 |

28.4 |

0.6% |

||

Source: Figures taken from – British Petroleum Statistical Review of World Energy 2019

Energy Dynamics between EU and Central Asia

With the objective of diversification of energy sources, the EU is trying to identify new partners and is building new supply routes to reduce its dependence on any single major supplier. This is where the Central Asian region becomes crucial. The cooperation with these countries on the issue of energy diversification dates back to 1991 with the establishment of Technical Aid to the Commonwealth of Independent States (TACIS)i programme of which energy was of key importance. TACIS was aimed at addressing several issues relating to energy production like lack of investments, environmental issues, etc. Under this programme, apart from technical assistance, significant funds were allocated to modernising the energy networks of the region. By 1995, TACIS programme established the Interstate Oil and Gas Transport to Europe Project (INOGATE).

INOGATE included partner countries in three geographical areas – Eastern Europe (Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine), Caucasus (Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia), and Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan). It has four major objectives: “converging energy markets on the basis of principles of EU’s internal energy market, taking into account particularities of partner countries; supporting sustainable energy development; attracting investments in various projects, and enhancing energy security by addressing issues of supply diversification, energy transit and demands”. Till date INOGATE has successfully implemented 70 projects in the partner countries.7 To bring together the supply and transit countries on one platform, the EU launched Baku Initiative in November 2004 during the Energy Ministerial Conference in Baku. This initiative brought together EU with the littoral states of the Caspian Sea and the countries of Eastern Europe and Central Asiaii. The Baku Initiative set out several parameters for the future engagements on energy issues, which included modernisation and implementation of new infrastructure so as to develop new inter-connections, promotion of investments for new commercial projects, integration of energy systems, upgrading of legal and technical standards.8

Apart from the regional level cooperation, EU also engages with the countries of Central Asia bilaterally on the issue of energy. Energy forms one of the 29 key policy areas of ties between EU and Kazakhstan as enshrined in the Enhanced partnership and Cooperation Agreement, signed in 2015 and in provisional application since 2016, as the ratification process is still pending in several EU member states. The EU is Kazakhstan’s largest trading partner, with 40% share in its total trade. Major exports to EU include oil and gas, which account for almost 80% of the country’s total exports.9 EU-based companies are also present in the country. The Italian ENI has been actively present in Kazakhstan since 1992. It is co-operator of the Karachagnak field (29.25% interest) and partner in the North Caspian Sea Production Sharing Agreement (NCSPSA) in which it holds 16.81% interest. NCSPSA sets the terms for the exploration and development in the Kashagan field. It also jointly cooperates with Kazakh state company KazMunayGas and has an agreement to receive 50% of Isatay block which has significant potential oil reserves.10 Similarly, French oil company Total has been present in Kazakhstan since 1992. Total also increased its investment in the country in 2017, after the acquisition of the Danish company Maersk Oil for US$7.45 billion.11 Moreover, as a member of NCAPSA, it has 16.81% share in the Kashagan field. It also has a 60% share of the Dunga field, located in the south-western Mangystau region. Dunga field has been on-stream since 2000 and currently produces about 15,000 barrels per day.12

EU-Turkmenistan energy relations are governed by the MoU on reinforcing mutual cooperation in the field of energy signed in 2008. This MoU is aimed at increasing bilateral energy cooperation in areas like production, energy technology, energy efficiency, transport and trade of energy products etc.13 However, the presence of European companies is limited to the Italian company ENI. ENI began its activities in Turkmenistan in 2008.14 It has also enhanced its presence in the country by signing the Production Sharing Agreement (PSA) for the onshore Nebit Dag Area located in West Turkmenistan in 2014. The agreement extends the duration of the PSA till 2032. Also, it has signed a MoU in 2014 with the Turkmen State Agency for Management and Use of Hydrocarbon Resources for the exploration and extension its activities in Turkmenistan’s offshore sector in the Caspian Sea.15

EU-Uzbekistan relations are under the MoU on Cooperation in the field of energy signed in 2011. The energy relations are not very well developed between the two partners due to various reasons like lack of infrastructural development, higher domestic needs of Uzbekistan etc. Also, European companies have minimal presence in Uzbekistan. However, there have been some developments in the last two-years, particularly with new government coming to power in the country. The UK signed a MoU in 2018 with the Uzbekistan Fund for Reconstruction and Development for financing of investment projects in oil and gas, energy efficiency and renewable energy. The UK committed £1.25 billion for financing these projects.16 In the field of renewable energy, a contract was signed between the French Total EREN and UzbekEnergo in 2018 to jointly implement a solar power plant project in Samarkand.17

A special reference needs to be made to the Caspian Sea region which has emerged to be an area of vital interest for the European countries. According to EIA estimates, the Caspian Sea countries – Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Iran – together hold almost 48 billion barrels of oil and 292 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in proven and probable reserves18. Individually, Azerbaijan plays a crucial role in the European Union’s quest for the diversification of sources. It is estimated that the export of natural gas from Azerbaijan to European countries is poised to increase in near future with the Union considering the plans to connect Shah Deniz natural gas field to southern Europe because of the development of South Gas Corridor (Figure 3). The Southern Gas Corridor is an ambitious plan of the EU which aims to reduce Europe’s reliance on Russia supplies. It is expected to be 3,500 kms in total length with an investment of approximate US$40 billion. The gas corridor is envisaged as a system of inter-connected pipelines which would run through Caspian Sea region towards Turkey to South-eastern and Central Europe. The inter-connected pipelines includes – South Caucasus Pipeline which has been operational since 2006 runs from Azerbaijan-Georgia-Turkey; Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) which runs from Turkey’s eastern border to Greece border, began its operations in 2018 and Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) which runs from Greece through Albania to Italy, is expected to be completed in 2020. According to Energy Information Administration estimates, of the expected 565 bcf (billion cubic feet) of natural gas production at the Shah Deniz 2, Turkey is expected to receive 211 bcf, and the rest would go to Greece, Bulgariaiii, Albania, and Italy from where it will possibly flow north to Central Europe.19

Figure 3: Southern Gas Corridor

Another area of cooperation between EU and Central Asian countries is in the field of uranium exports. Kazakhstan remained the world’s leading uranium producer in 2018, accounting for 41% of total uranium output. The country’s uranium production accounted for 21,540 tU in 2018. Uzbekistan accounted for 5% of total worldwide uranium output with a total production of estimated 2423 tU in 2018. As estimated by the EURATOM, there are 126 commercial nuclear power reactors operating in the EU in 14 Member States for which EU imports almost 92.4% of uranium from diverse sources. Central Asian countries play a vital role in this regards with Kazakhstan as the 5th largest exporter to the EU accounting almost 13.7% (1,754 tU) of the total exports and Uzbekistan is the 7th largest accounting for 1.3% (166 tU).20 EU has also been actively cooperating with the Central Asian countries are in its support for environmental remediation measures to address the “legacy of toxic chemical and radioactive waste from past uranium mining in the region”.21 The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) had set up a fund called Environmental Remediation Account for Central Asia (ERA) of an initial €8 million in 2015 to deal with the radioactive contaminated material resulting from Soviet-era uranium mining and processing in the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. In August 2016 the Kyrgyzstan government announced rehabilitation works to begin in mid-2017, in collaboration with Tajikistan and Russia as well as the IAEA, and funded by the EBRD. The EBRD signed framework agreements with the Uzbekistan, Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan in January 2017. To date the fund has received €17 million in contributions.22

Assessing the Energy Relations

The EU’s strategies of 2007 and 2019 on Central Asia laid down the priorities for the partnership and aimedto formulate a plan keeping each country’s aspirations in mind. As stated in the strategy 2019, “While respecting the aspirations and interests of each of its Central Asian partners, as well as maintaining the need to differentiate between specific country situations, the EU will seek to deepen its engagement with those Central Asian countries willing and able to intensify relations.”23 The EU has been active in the region for past three decades and has been instrumental in providing funds for the development of the region. Central Asia also features prominently in the EU’s vision of diversification of its energy sources. Many European companies are already present or are vying for a foothold in the region.

Despite the Union’s commitment to the region, EU is still making efforts to exert tangible influence in Central Asia. This is because of three factors - first is the Russian presence in the region. Russia is not only a major trading partner of these countries, but also shares cultural, political and social links. Russia has also enjoyed an almost monopolistic presence in the energy market of Central Asia by getting considerable share of oil and natural gas from the region at prices permitting profitable resale in Europe.24 Russia also hosts a large number of labour migrants from these countries. Second, China in the past few years has emerged as a major trading partner for these countries. Through its Belt and Road Initiative, China has invested considerable amount of money in the development of infrastructure and manufacturing sector in the region. Beijing has also signed major energy deals with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Third, Europe’s insistence on human rights and governance is not appreciated by the Central Asian countries, as too often this approach of EU has produced more obstacles than benefits in the way of strengthening relations.

Nonetheless, Europe is trying to gain a foothold in this region. European Union has started to look at Central Asian countries as essential partners in its efforts to identify possible alternative sources for energy needs. It is not, as if, there were no bilateral trade in energy, the problem is largely the limited presence of European companies and partners in the region; and the inherent contradictions in EU’s policies towards Central Asia, which on one hand pushes for diversification of energy sources, and tries to maintain stable relations with Russia, on the other. The idea of energy diversification, away from Russian sources, has become a central issue for the Union. The situation has been aggravated after the price disputes between Russia and Ukraine in 2006 and 2009, and then in 2014 with the Crimean crisis and the consequent sanctions imposed on Russia by EU. Moreover, as the Central Asian region has substantial Russian presence, the EU has been trying to carefully manoeuvre without adversely affecting its relations with Russia.

The major routes for the energy transport runs through Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) which is a series of inter-connected pipelines (South Caucasus, TANAP, TAP) carrying gas resources from Shah Deniz field to Southern Italy. EU, since the Ukrainian crisis, has started to pay more attention to this area, especially to Turkmenistan. The Union has been actively endorsing the construction of the Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP), which is an underwater pipeline stretching from Turkmenistan coastal region of Turkmenbashi to Baku in Azerbaijan, which in future can further be extended to connect Turkmenbashi to the Tengiz field in Kazakhstan.25 The project is expected to transport natural gas from Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan to EU, thereby bypassing Russia. The project is stalled because of Russian opposition. This pipeline, envisioned as an extension of the SGC through Caspian Sea, is expected to link Caspian Sea countries, especially Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, to Europe through Turkey. Gazprom stands to lose its current prominent share in the European markets once this pipeline is functional. As Russia is also a transit location for Turkmen gas, with these pipelines becoming functional, the former stands to lose its transit fees to Georgia. Also, Russia has expressed serious environmental concerns regarding the pipeline running under the Caspian Sea.26

The renewed approach by the Union towards the region highlights EU’s redefinition of its interests by taking into account the changing global realities. While the 2007 Strategy drew on Central Asia as a region of strategic location and resources, the current Strategy draws on the aim of maintaining security and stability in the region as well as be able to tap into the energy and connectivity potential of the region. While enhanced energy cooperation through the inclusion of future Kazakh and Turkmen gas supplies to Europe appears complicated given Russia’s objections, still the TCP discussion highlights EU’s ambition in formulating its own energy security policy and its long-term strategic vision for reducing energy dependence on Russia.

***

* The Authoress, Research Fellow at Indian Council of World Affairs, New Delhi.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are that of the Researcher and not of the Council.

End Notes

iIn 2007, TACIS Programme was replaced with a broader instrument called Development Cooperation Instrument which has a wider range of objectives like poverty reduction, economic development, health governance etc.

iiThe Caspian Littoral States - Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and the Russian Federation; and Armenia, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Turkey, Ukraine and Uzbekistan

iiiGreece and Bulgaria have signed an agreement of construction of 220 million euros Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria in southern Bulgaria to receive gas from TAP.

1*Joint Communication on the EU and Central Asia – New Opportunities for a Stronger Partnership, EEAS, 15 May 2019, https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/joint_communication_-_the_eu_and_central_asia_-,_new_opportunities_for_a_stronger_partnership.pdf, Accessed on 25 July 2019

2*Central Asia, International Cooperation and Development, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/regions/central-asia/central-asia_en, Accessed on 18 July 2019

3*The EU's new Central Asia strategy, Briefing, European Parliament, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2019/633162/EPRS_BRI(2019)633162_EN.pdf, Accessed on 19 July 2019

4*Central Asia Invest, International Cooperation and Development, European Commission, 2015, https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/sites/devco/files/brochure-central-asia-invest-2015_en.pdf, Accessed on 19 July 2019

5*Energy Security – Diverse, Affordable and Reliable Energy, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/energy/en/topics/energy-security, Accessed on 19 July 2019

6*EU imports of energy products – recent developments, Statistics Explained, Eurostat, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=EU_imports_of_energy_products_-_recent_developments#Overview, Accessed on 20 July 2019

7In Brief, INOGATE, http://www.inogate.org/pages/1?lang=en#, Accessed on 20 July 2019

8 *CONCLUSIONS of the Ministerial Conference on Energy Co-operation between the EU, the Caspian Littoral States and their neighbouring countries, https://library.euneighbours.eu/content/baku-initiative-conclusions, Accessed on 20 July 2019

9*Kazakhstan, EU’s Relations with Country, EEAS, https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/1367/kazakhstan-and-eu_en, Accessed on 21 July 2019

10Overview, ENI’s Activities in Kazakhstan, ENI,https://www.eni.com/enipedia/en_IT/international-presence/asia-oceania/enis-activities-in-kazakhstan.page, Accessed on 21 July 2019

11Total acquires Maersk Oil for $7.45 billion in a share and debt transaction, News, Total 21 August 2017, https://www.total.com/en/media/news/press-releases/total-acquires-maersk-oil-for-7-45-billion-dollars-in-share-and-debt-transaction, Accessed on 21 July 2019

12Total in Kazakhstan, 20 September 2017, Total,https://www.total.com/en/kazakhstan, Accessed on 22 July 2019

13The EU and Turkmenistan strengthen their energy relations with a Memorandum of Understanding, EU Press Releases, 26 May 2008, European Commission, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-08-799_en.htm, Accessed on 22 July 2019

14Overview, ENI’s Activities in Turkmenistan, ENI, https://www.eni.com/enipedia/en_IT/international-presence/asia-oceania/enis-activities-in-turkmenistan.page?lnkfrm=serp, Accessed on 23 July 2019

15Eni strengthens its presence in Turkmenistan, 18 November 2014, ENI, https://www.eni.com/en_IT/media/2014/11/eni-strengthens-its-presence-in-turkmenistan, Accessed on 23 July 2019

16The Tashkent Times, 19 April 2018, https://tashkenttimes.uz/economy/2287-uk-commits-1-25-billion-for-energy-sector-project-trade-financing-in-uzbekistan-of, Accessed on 23 July 2019

17Strategeast Post, 9 October 2018, https://www.strategeast.org/uzbekenergo-french-total-eren-ink-deal-for-solar-power-plant-in-uzbekistan/, Accessed on 24 July 2019

18Overview of oil and natural gas in the Caspian Sea region, EIA Estimates, 26 August 2013, https://www.eia.gov/beta/international/regions-topics.php?RegionTopicID=CSR, Accessed on 11 August 2019

19Azerbaijan to become a more significant supplier of natural gas to Southern Europe, EIA, 14 February 2019, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=38352, Accessed on 24 July 2019

20 EURATOM Supply Agency, Annual Report 2018, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/euratom/ar/last.pdf, Accessed on 27 August 2019

21 The EU and Central Asia: New Opportunities for a Stronger Partnership, JOINT COMMUNICATION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL, European Commission, 15 May 2019, https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/joint_communication_-_the_eu_and_central_asia_-_new_opportunities_for_a_stronger_partnership.pdf, Accessed on 27 August 2019

22 Rallying support for Central Asia to address uranium mining legacy, EBRD News, 27 September 2018,

https://www.ebrd.com/news/2018/rallying-support-for-central-asia-to-address-uranium-mining-legacy.html, Accessed on 27 August 2019

23*Joint Communication on the EU and Central Asia – New Opportunities for a Stronger Partnership, EEAS, 15 May 2019, https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/joint_communication_-_the_eu_and_central_asia_-_new_opportunities_for_a_stronger_partnership.pdf, Accessed on 25 July 2019

24Martin C.Spechler and Dina R.Spechler, Russia’s lost position in Central Eurasia, Journal of Eurasian Studies, Volume 4, Issue 1, January 2013, Pages 1-7

25New Europe, 8 February 2018, https://www.neweurope.eu/article/trans-caspian-gas-pipeline-really-important-europe/, Accessed on 25 July 2019

26Still One Big Obstacle To Turkmen Gas To Europe, Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, 5 May 2015, https://www.rferl.org/a/turkmenistan-natural-gas-europe-trans-caspian-pipeline/26996003.html, Accessed on 11 August 2019