Indian Council of World Affairs

Sapru House, New DelhiEmulating the EU-Turkey Migration Deal: EU’s Search for New Frontiers

Abstract:

The EU-Turkey deal is claimed to have succeeded in achieving a reduction in the number of refugees and asylum seekers coming to Europe and is completing 3 years of implementation in March 2019. This paper analyses the contours of the deal and assesses whether it has been effective. Further, it also looks at the question of whether the deal can serve as a model that can be emulated in Africa. It argues that the EU-Turkey deal may have been able to achieve a reduction in the number of people reaching the shores of Europe but many of the promises of the deal remain unfulfilled. The deal does not delve in to the question of protection of migrants leading to criticism from many human rights groups and also does not engage with the issue of addressing the long term goals of managing migration. Given the limitations of the deal and Turkey’s unique relationship with Europe coupled with the politico-socio-economic situation of African countries, the deal does not present itself as a model that can be emulated in Africa.

Introduction

It has been almost three years since the European Union (EU) -Turkey migration deal came in operation in March 2016. The trigger for the deal was the 2015 crisis when Europe was burdened with increasing numbers of refugees coming to European shores in the wake of Syrian crisis. Under pressure to act, EU struck a deal with Turkey in March 2016 to stem the flow of migrants. Since then, there has been a reduction in numbers of those migrating to Europe via the Aegean sea route.

As is wont, many assessments pour in when an anniversary of a deal, otherwise relegated to the background is around the corner. This paper however seeks to go one step ahead by not only analyzing the contours of the EU-Turkey migration deal but also looks at whether it can serve as a template for EU to pursue an understanding on migration with African countries.

Contours of the EU Turkey Deal

In 2015, at the height of the refugee crisis, people fleeing the war in Syria were using the Eastern Mediterranean Sea Route - the sea route from Turkey to Greece, to reach Europe. Turkey, given its geographical location was the transit point used by refugees to cross over to Europe. The islands of Greece were burdened beyond capacity to process the claims of these individuals, forcing EU to come to an understanding with Turkey. The EU estimated that around 885,000 came through Greece1, and the asylum and application system in Greece lacked the capacity to deal with the burgeoning numbers.

Turkey, on the other hand, a claimant to EU membership since 1987, was undergoing its own difficulties. The country had been hosting refugees fleeing the conflict since 2011 and it was under tremendous financial strain. The Regional Response Plan released by UNHCR in 2012 recognized the needs of countries such as Turkey, and adjoining countries such as Lebanon and Jordan hosting the refugee population.2 The prospect of making a deal with EU also held the allure of reviving the accession talks with EU which had long been dormant due to various reasons and the promise of visa liberalization for Turkish citizens. It is significant to note that EU underwent two waves of enlargement between 2004 and 2007, when many countries of Central and Eastern Europe became EU members, and Croatia joined the bloc in 2013, while Turkey waited on the horizons. It was hoped that arriving at a deal with EU would accelerate the negotiations.

In these circumstances the EU-Turkey deal was signed on 18 March, 2016. At the core of it is a swap agreement whereby for every Syrian refugee returned to Turkey from Greece, EU would resettle a Syrian Refugee in Europe. This gives rise to the question of how this provision was to be operationalised. Under the framework of the deal, individuals who did not apply for asylum in Greece or whose applications were deemed to be non-admissible were to be returned to Turkey. The legal basis to this exercise was provided by Greece and Turkey and EU-Turkey Readmission Agreement, in line with international law requirements and based on the principle of non- refoulement. The document declares Turkey as a ‘safe third country’ so that the returns are not considered as refoulement.3 Further, Turkey was required to take necessary actions to stop irregular crossings between Turkey and EU through land or sea routes, and it was agreed that the accession negotiations will be re-energized.4 Visa liberalization with a view to lifting the visa requirements for Turkish citizens was also envisaged as part of the agreement. A €3 billion Refugee Facility for Turkey was created as part of the agreement initially with € 1.4 billion as humanitarian assistance for basic needs, and € 1.6 billion as non-humanitarian assistance for livelihoods, health and education.5 The task of implementing the deal, though a collective effort, was given to Greece and Turkey.

As Europe wanted to see a reduction in number of refugees and amidst growing political tensions, it negotiated the deal with Turkey. Turkey’s benefit from the agreement was twofold: the Facility for Refugees in Turkey provided financial support for migrant and refugee populations as Turkey was under considerable strain given the scale of movements and, it was also supposed to reenergize its long-stalled EU accession process.

Has the deal been effective?

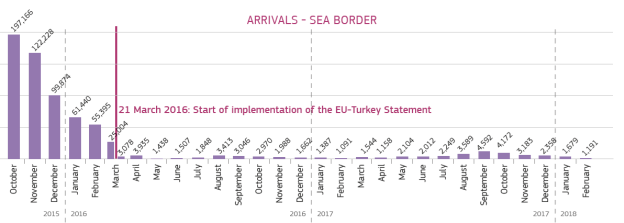

Any assessment of the EU-Turkey deal has to take into cognizance the extent to which it has been able to meet its avowed aims and the criticism leveled against it. If an assessment was to be made merely based on numbers, then the deal has been able to achieve a significant reduction in the number of border crossings. The European Union has argued that arrivals have been 97 per cent lower than the period before the deal became operational (See Figure 1).Sea arrivals have dropped down to 28,495 till November 2018 compared to 856,723 in 2015.6

To protect its land borders, EU has been fencing its borders along the Balkans with barbed wires and fences. Turkey did not sit idle either, and began the construction of a wall along the 911 km wall along border it shares with Syria to prevent border crossing from Syria into Turkey.7Turkey has so far constructed 765 km of the wall.8

(Source: European Commission 2018)

The population that this deal seeks to address is large. Turkey hosts one of the largest refugee populations of 3.9 million refugees.9Share of women and children is around seventy per cent. The condition of these refugees in Turkey varies. Each Syrian refugee has been provided with a temporary guest card and free access to public health care. Some Syrians have been able to obtain a work permit and it is estimated that around half a million refugee children have been sent to school but many still do not have access. Child labour cases have also been reported. To cater to the needs of these groups, the first tranche of €3 billion has been contracted to 72 projects and under the second tranche of € 3 billion; €450 million has been committed till date by the EU member states.

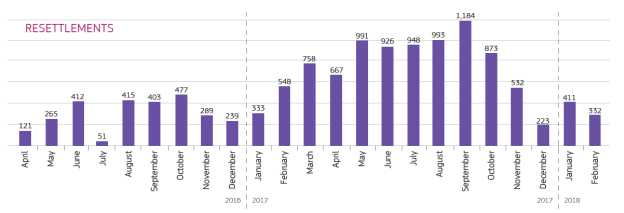

In Greece, the other implementing partner of the deal and a member of European Union, the situation is far from satisfactory. Under the EU Turkey deal, the refugees and asylum seekers are restricted to the islands in which they arrive until their asylum claims are registered leading to dire conditions in camps. The camps are overcrowded and according to UNHCR, there were 60,000 refugees and migrants in Greece till June 2018.10 The mayor of Lesbos, Sypros Galin remarked in 2017 that the refugee facility in Greece was starting to resemble “concentration camps, where all human dignity is denied.”11Resettlement of refugees, a crucial plank of the deal, has moved at a very slow pace. From April 2016 to March 2018 only 12,170 refugees have been resettled from Turkey to Europe. The top countries of resettlement have primarily been UK, France, Germany, Netherlands and Norway which have taken 78% of all resettlements.12

Many of the provisions of the deal such as visa liberalization for Turkish citizens are yet to be implemented. Turkey still has to meet EU’s conditionalities such as biometric passports, cracking down on corruption, cooperate on extradition requests, and reduce the scope and extent of anti terror laws.13The deal was also threatened by the July 2016 coup attempt in Turkey but Turkey’s need for financial support and EU’s requirement of managing migration flows saved the day. The agreement has withstood the threats of scrapping the deal as Turkey needs the money flowing from EU.

There also has been criticism of the deal. Many human rights groups have argued that though the deal has been able to achieve a reduction in numbers, it pays scant attention to the rights and protection accorded to the refugees given the high standards of EU’s human rights law. The deal has led to a situation whereby the EU had to make concessions on issues such as right to appeal.14 They postulate that the deal fails to protect the refugees because the objective is not protection but border control and burden shifting. For the first time EU is implementing a policy of returning the refugees because they arrived from a safe country. According to the deal, if a refugee came via Turkey, which is deemed a ‘safe third country’, they would be liable for return. This designation of Turkey as a safe third country has upset the human rights groups which argue that instead of building pressure on Turkey to improve the condition of refugees, it incentivizes the opposite.15 EU has also been criticized for segregating among refugees, giving preference to Syrians over others, and for lowering down its standards to make the deal work and looking away when Turkey clamped down on freedom of expression.

Can the deal be emulated in Africa?

Africa has been the transit point for migrants coming to Europe through the three routes, Eastern Mediterranean Route (via Turkey and Aegean Sea), Central Mediterranean (through Libya to Italy) and Western Mediterranean Route (from Morocco and Algeria to Spain). This year European policy makers have repeatedly emphasized the need to reach an understanding with African countries to manage migration and also set up disembarkation platforms in Africa. Can EU’s deal with Turkey be emulated in Africa? The answer seems to be in the negative. During Malta’s presidency of the European Union in 2017, the prospect of offering a similar deal to Libya was rejected by the European Commission. EU’s relationship with Turkey is vastly different where Turkey has been waiting in the wings for a membership of the EU for long and its economic and political conditions also put it on a different pedestal as compared to the African countries. Further, the agreement with Turkey rests on the premise of Turkey being a safe third country or a safe first country of asylum; this cannot be done in the case of African countries without having to face criticism and departing from “European” principles of liberty, rules of law and a respect for human rights. The countries in North Africa have not been very enthused with Europe’s idea of relegating the task of managing migrants to Africa, and Europe seems to be taking cognizance of these factors. In a recent event held in Tunisia, on being asked about the plan to set up migrant camps in North Africa, European Commission’s President Jean Claude Juncker remarked that “This is no longer on the agenda and never should have been.16”

Concluding Remarks

EU-Turkey deal achieved its purported aim of a reduction in numbers, but it also sets a precedent of affecting a migrant’s right to seek refuge. While Turkey has been generous in hosting refugees in the hope of reviving negotiations on accession to EU, the two years in which the deal has been operational has seen scant progress in this direction. The promise of visa liberalization has not been achieved and returns and resettlement of refugees have moved at a very slow pace. As the analysis of EU-Turkey deal suggests, Turkey’s close proximity to Europe and its pending candidature allowed it to conclude a deal with EU. This may not be replicated in Africa.

Europe today seems to have gone back to its earlier policies of securitizing migration and fortifying its border. There is a trend towards shifting the burden to third countries where EU can use its leverage and prevent migrants and refugees to come to the European soil in the growing polemic surrounding migration. There is a need to view the issue of migration along with the turmoil in Middle East and Asia from where most of the refugees coming to Europe originate. Unless political stability and issues of turmoil plaguing these parts are addressed, Europe may not find a long term solution to addressing the question of migration management.

***

* The Authoress, Research Fellow, Indian Council of World Affairs, New Delhi.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are that of the Researcher and not of the Council.

Endnotes

1 European Commission (2017), Accessed on 5 November 2018, URL: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/background-information/eu_turkey_statement_17032017_en.pdf

2 UNHCR (2012), “Second Revision- Syria Regional Response Plan”, Accessed on 10 November 2018, URL: https://www.unhcr.org/partners/donors/5062c7429/second-revision-syria-regional-response-plan-september-2012.html

3 Haferlach Lisa and Dilek Kurban (2017), “Lessons Learnt from the EU-Turkey Refugee Agreement in Guiding EU Migration Partnerships with Origin and Transit Countries”, Global Policy, Vol 8, Supplement 4

4 European Commission (2016), “ Implementing the EU-Turkey Statement”, Accessed on 12 November 2018, URL: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-16-4321_en.htm

5 European Commission, “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council”, Accessed on 15 Novermber 2018, URL: https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/14032018_facility_for_refugees_in_turkey_second_annual_report.pdf

6UNHCR (2018), Accessed on 20 November 2018, URL: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean/location/5179

7 Vammen Ida Marie and Hans Lucht (2017), “Refugees in Turkey struggle as border walls grow higher”, DIIS Policy Brief, 18 December 2017.

8 Daily Sabah (2018), “Turkey finishes construction of 764-km security wall on Syria border”, 9 June 2018, Accessed on 12 November 2018, URL:

https://www.dailysabah.com/war-on-terror/2018/06/09/turkey-finishes-construction-of-764-km-security-wall-on-syria-border

9European Commission (2018) “Turkey Factsheet” Accessed on 15 November 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/echo/where/europe/turkey_en

10 Al Jazeera (2018), “Refugees in Greece hopeless as Europe eyes more returns”, Accessed on 14 November 2018, URL: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/07/refugees-greece-hopeless-europe-eyes-returns-180712210255913.html

11 The Guardian (2018), “Greece has the means to help refugees on Lesbos – but does it have the will?, Accessed on 16 November 2018, URL :https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/sep/13/greece-refugees-lesbos-moria-camp-funding-will

12 UNHCR (2018), “Europe Resettlement” Accessed on 17 November 2018, URL: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/66830

13 The Economist (2016), “Europe’s murky deal with Turkey”, Accessed on 18 November 2018, URL:https://www.economist.com/europe/2016/05/26/europes-murky-deal-with-turkey

14 Migration Policy Institute (2016), “The Paradox of the EU-Turkey Refugee Deal”, Accessed on 20 November 2018, URL: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/paradox-eu-turkey-refugee-deal

15 The Economist (2016), “ Why the EU-Turkey deal is controversial”, Accessed on 21 November 2018, URL: https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2016/04/11/why-the-eu-turkey-deal-is-controversial

16 Reuters (2018), “Juncker says North Africa migrant 'camps' not on EU agenda”, Accessed on 22 November 2018, URL: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-europe-migrants-africa/juncker-says-north-africa-migrant-camps-not-on-eu-agenda-idUSKCN1N01TU